Justine Wintjes, KwaZulu-Natal Museum

In the archaeology storerooms of the KwaZulu-Natal Museum in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, lie two boxes filled with seashells.

The shells form a bright and shiny mass that makes a satisfying, almost metallic sound when you run your fingers through them. The entire sample weighs 18.7 kg and comprises approximately 16,500 individual shells.

They are money cowries, from Monetaria moneta, a species of sea snail native to the tropical waters of the Indian Ocean.

Money cowries are natural objects – each shell is a trace of an animal’s life. They were also, as their common name suggests, circulated widely as a kind of currency.

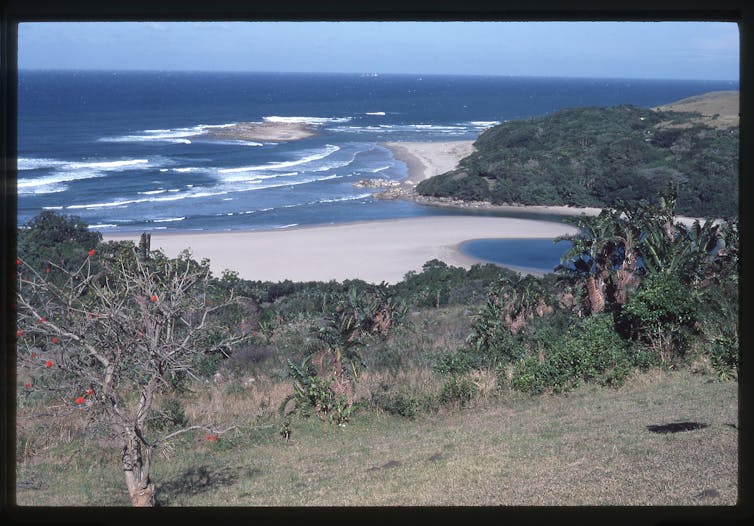

The KwaZulu-Natal Museum specimens were found among the remains of a sunken ship lying at the mouth of the Mzikaba river in what is today South Africa’s Eastern Cape province.

The remains were long thought to be of the Grosvenor, wrecked in 1782. But in the early 1980s they were identified as the wreck of the São Bento, a 16th century Portuguese vessel. The São Bento sailed from Portugal to India in 1553, where it loaded a new cargo to take on its journey homeward. It departed from the port of Cochin in February 1554 with goods destined for trade into Europe and West Africa.

The ship encountered rough and stormy conditions and was probably too heavily laden – greed and risk played a significant role in the Portuguese trading venture. By April the São Bento was struggling around the south-eastern corner of Africa. It drifted onto a reef-and-island cluster adjacent to the shoreline and broke up in the rough surf.

It would be centuries before the wreck was investigated; in the late 1960s, divers formed an amateur salvage and research group to explore what remained. Numerous items were accessioned into the KwaZulu-Natal Museum’s archaeology collection, including beach finds such as ceramic sherds and carnelian beads, and bronze cannons recovered from beyond the reef.

The cache of money cowries was found during conservation work in the deepest recesses of the barrel of one of the cannons. The shells were packed tightly into the barrel, as if stashed there in secret. They probably represent a small (possibly pilfered) fraction of a much larger shipment that would have been swept away by the current after the accident.

Their presence, as I have outlined in my research, tells a richly layered, unavoidably dark story about the West African slave trade. Through the story of the cowries, at least some small part of this history may become more tangible.

“Human-cowrie conversion”

Money cowries were used for thousands of years as currency across the Indo-Pacific world, but introduced into Atlantic commercial networks relatively late. The Maldives was a major source, with its large-scale, sustainable money cowrie industry.

In the 1550s cowries were still a relatively new commodity for Europeans, and they were destined primarily for trade with West Africa. The Atlantic market picked up swiftly and billions of money cowries from the Indian Ocean were shipped to the Bight of Benin on the West African coast between the 16th and 19th centuries.

Cowries were exchanged directly for slaves throughout all centuries of the sea-borne trade of slaves out of West Africa. Nigerian archaeologist, anthropologist and historian Akinwumi Ogundiran describes this trade in terms of a “human-cowry conversion”.

Exact numbers are impossible to calculate, but at a possible rate of around 6 kg of cowries (5000–6000 shells) for one slave, the São Bento cache could have been used to purchase three slaves.

Read more: A long view sheds fresh light on the history of the Yoruba people in West Africa

The São Bento cowries had another intimate association with slaves: according to the report by survivor and chronicler Manuel de Mesquita Perestrelo, slaves made up around two-thirds of the ship’s 470 passengers. This mention is intriguing because little is known of the transport of slaves around the southern tip of Africa in the 16th century. The Indian Ocean slave trade is far older than the Atlantic system, but it is a neglected area of history.

Read more: Exploring the Indian Ocean as a rich archive of history – above and below the water line

Early Portuguese shipwrecks with oriental cargoes like the São Bento could contribute to our understanding of this deeper history of slavery, and the relationship between the two ocean worlds.

Entanglement

More research might determine where the São Bento slaves came from, and even what it meant to be a slave in this context. Whatever the specific situation for the São Bento slaves, the sinking of the ship might have opened other options up for them. Ultimately only 23 people were rescued by a Portuguese ivory-trading vessel at the end of a gruelling 800 km walk from the wreck site to Delagoa Bay on the southeast coast of Mozambique. Just three of them were slaves.

Despite its sinking, then, the entanglement between slaves and cowries was so fundamental that the São Bento still effected a kind of human-cowrie conversion: three surviving slaves shipped out of Delagoa Bay half a year after the accident for three slaves’ worth of salvaged cowries bequeathed to a museum over four centuries later.

There’s another kind of entanglement at play, too. Cowries were not just currency: they began to serve as a raw material in West Africa for making art. Among the Yoruba, Ori shrines which facilitate the realisation of self-hood came to be constructed from large numbers of cowries. Even in this re-purposed context, the confluence with Ori bound cowries to a person’s destiny.

A vast legacy

Now as museum objects in South Africa, the brightness of the São Bento cowries in their boxes seems at odds with the heaviness they carry from their historical association with human slavery. This unsettling lightness is amplified by the sinister elusiveness of the specifics of this story, reminiscent of histories of slavery more generally. Irrecoverable, hidden, unspoken, and yet such a vast legacy.![]()

Justine Wintjes, Curator, KwaZulu-Natal Museum

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.