Jonathan Munemo, Salisbury University

The global economic crisis triggered by the outbreak of the COVID pandemic in 2020 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February this year has intensified the risk of declining trade integration between countries. A process referred to as the deglobalisation of trade.

The pandemic sent shocks through supply chains across the world. As a result, companies in some advanced economies have started to prioritise bringing production that was previously outsourced to Asia back home – or closer to home. The expectation is that this will avert ongoing – and future – supply-chain disruptions, ensuring a steady and reliable supply of goods.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has exacerbated global supply shortages after the pandemic. It is also further fuelling expectations of major reduced reliance on global supply chains by businesses. This is particularly true of companies in Europe and the US.

This trend risks adding additional strain to economies in Africa on top of the current economic pain from soaring food and fuel price inflation imposed by the war in Ukraine. A deglobalising world poses serious risks for Africa. This has been confirmed by findings in a recent World Bank report. It shows that reversing globalisation through reshoring of value chains has the potential to push an additional 52 million people into extreme poverty.

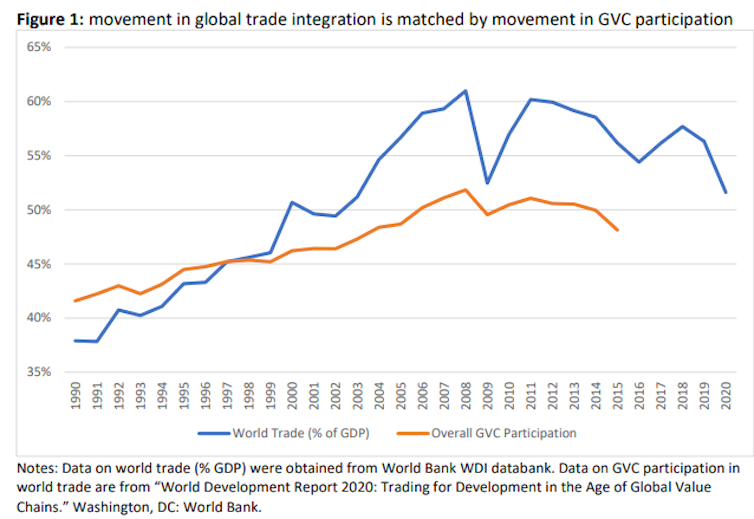

Those living in Sub-Saharan Africa would be the hardest hit. It would make Africa a poorer place. As shown in Figure 1, global trade integration (trade’s share of global GDP) sped up after 1990, and then slowed down after reaching a peak in 2008 when the financial crisis caused an economic downturn. The remarkable rise in global trade integration during the 1990s and 2000s is intimately tied to the rapid growth in global value chain trade.

Why being connected matters

Connecting to the global economy is vital for spurring growth and development on the continent. This is because it creates opportunities for firms to specialise in specific tasks. In turn this allows them to integrate into parts of a global value chain even when they lack the competitive advantage to produce an entire product domestically.

In addition, greater participation in global value chains provides African firms with better access to capital, technology and other inputs needed to upgrade products and become more diversified. This is important to point out, given that African firms face significantly higher costs that reduce their capacity to compete in regional and international markets. These costs are particularly crippling for small and medium enterprises (SMEs), the backbone of many African economies.

Entry into global value chains is therefore crucial for a number of reasons. Firstly to boost the growth of African SMEs, secondly to support the African Continental Free Trade Area in advancing regional trade integration, thirdly in diversifying production and export structures, and finally promoting the pick-up of industrialisation.

Over time, these positive economic outcomes will substantially reduce poverty in Africa. This will be reminiscent of the impact of the second wave of globalisation which rapidly accelerated after 1990. This helped some Asian and emerging economies lift millions out of poverty by supporting their integration into global value chains and narrowed the income inequality gap between advanced economies and the developing world.

The shift

A range of companies are relocating their manufacturing plants.

Among them are the motorbike and electric bicyle manufacturer Pierer Mobility. It is building a plant in Bulgaria so that it’s closer to its main customers in Europe. The German suit maker Hugo Boss has also moved manufacturing closer to home.

In the US, Stanley Black & Decker has expanded its tool making operations in North America. The aim is to support regional development of its supply chains and enable shorter time leads.

Apparel companies in the US also see supply-chain woes as an opportunity to reconsider bringing their supply chains home.

Governments in advanced economies are also reinforcing moves to re-shore production, mainly for geopolitical reasons. The EU now aims to boost its chip production. It has promised to back chip manufacturers such as Intel Corp with subsidies worth billions of dollars. The US is also planning to invest billions of dollars to bolster domestic chip production. And Japan is allocating huge funds to develop its semiconductor industry.

These substantial expenditures reflect the geopolitical significance of cutting-edge chips, which are vital for current and future technological advancement. The US and Europe chip investments are also motivated by competition with China and a desire to reduce reliance on Taiwan and South Korea as major suppliers, as they can be vulnerable to supply shocks and geopolitical conflicts in the region.

In addition to growing geopolitical rivalry and tensions between China and the West, the rise of nationalism in the West after the financial crisis of 2008/9 has also dampened enthusiasm for accelerating global trade integration.

In the US for example, former president Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” agenda was anti-global economic integration in nature and specifically promoted protectionist policies focused on reducing trade between China and the US.

Similar nationalist and anti-global moves were also happening across Europe, and were a major factor behind UK’s departure from the EU in 2020.

What now?

Globalisation is a powerful engine of global value chain integration that is important for Africa’s growth and development. African economies suffered greater scarring from the pandemic. The divergent recoveries between advanced and developing economies in Africa and other regions threaten to reverse gains in poverty reduction.

Absent of any decisive action, reshoring of production implies that trade will be dominated by a few powerful regional blocks in the future. These would likely include an Asian block dominated by China, an American-led block in North America, and an EU block.

If this happens, decades-long progress in global poverty reduction would be at high risk of being further derailed. It would make the world a poorer place and Africa would be the hardest hit by being severed from global value chains.![]()

Jonathan Munemo, Professor of Economics, Salisbury University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.