As a scholar of medieval magic, passing the magazine stand at the checkout counter is like stepping back in time. The women’s magazines promise sex tips that will keep him coming back for more. The men’s magazines guarantee six-pack abs in just six weeks and surefire techniques for getting commitment-free sex.

If these things really were surefire, would they have to publish new techniques every month?

But it’s not effectiveness that sells these magazines. It’s the hope.

Bronislaw Malinowski says that the function of magic is to ritualize optimism, to enhance “faith in the victory of hope over fear.” By this he means that when we perform magic, we ritualize our hopes, even if that ritual itself produces no effects. This only captures one aspect of magic, but it’s an important one.

Perfect sex and other miracles

There is a massive modern industry that leverages our vulnerabilties. Hundreds of scientifically unproven techniques offer not only power over love and sex, but health, wealth, good luck, influence over other people, improving appearance, intelligence and public speaking, assuring happiness and protection of self and family.

Modern books on magic like Starhawk’s The Spiral Dance and New Age handbooks like Shakti Gawain’s Creative Visualization have become classics over the past 40 years and have sold millions of copies. They cover pretty much the same ground. With few exceptions, the goals of medieval magic were identical to these personal growth manuals from the 1970s, and fulfilment in love tops the list.

Surely they figured out this didn’t work!

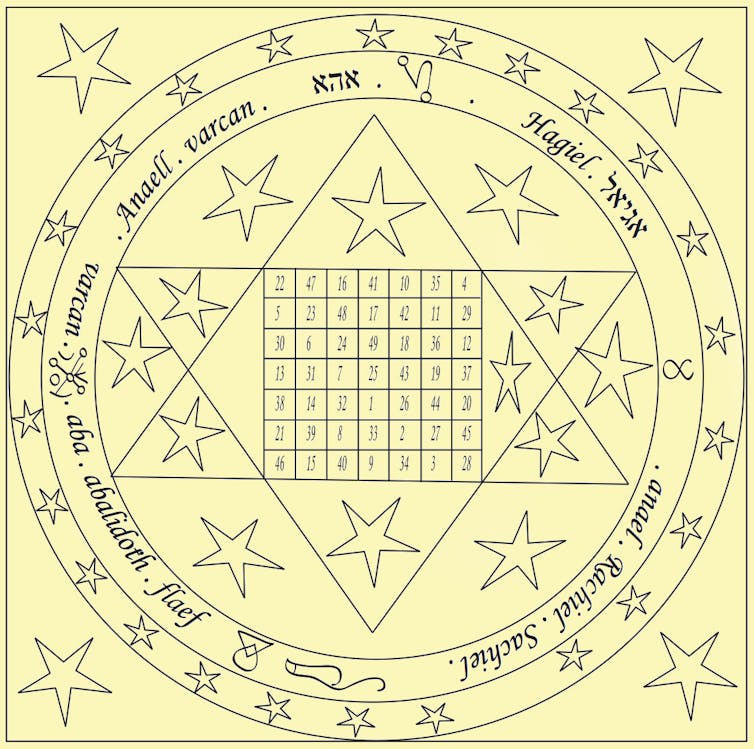

A late 16th century manuscript in the British Library, Sloane 3850, contains a collection of magic clearly meant for a man. There’s magic for success in gambling, hunting, fishing, and, most of all, sex and love.

The compiler and scribe was probably a nerd. He was literate, loved silly ciphers, and fancied himself as sophisticated. Just the sort who probably didn’t get the girl. It includes magic to determine whether a woman was a virgin or if she was being untrue. It also includes scores of charms and incantations to make women fall in love or lust with the magician. He could even conjure up a fairy queen to give him a ring of invisibility and then sleep with her afterwards. Commitment-free!

The thing is, there are a lot of love magic operations in this book and thousands more like them , scattered in various medieval and early modern manuscripts —some more innocent, some less. You wonder: How could they be so silly? Surely they figured out that these things didn’t work.

But then you’re standing at the checkout again, wondering if you could get abs like that.

Yeah. It’s all about hope.

Are we just stupid?

Medieval Arabic and Latin scholars were actually quite critical of magic and superstition. The medieval doctor Qusta Ibn Luqa talked at length about the placebo effect and how doctors should leverage it.

Medieval philosophers expended a lot of ink demonstrating how seemingly miraculous things were just natural effects, like magnetism. In fact, it was a bit of an obsession at the time. All in all, they were pretty skeptical.

To respond to these attacks, writers of medieval magic books often did exactly what their modern counterparts do — they tried to make them look like they were scientific. They used scientific ideas and language.

In comparison, one would think that modern people would be far less interested in magic, particularly given our advanced sense of how the physical world functions and the scientific educations we all get in public school. The fact that we don’t seem to be could be taken to mean that we are actually less intelligent than medieval people.

I don’t make this comparison to make fun of modern people who invest in miracle schemes, but for two other important reasons. First, it challenges the idea that scientific thinking somehow banishes magical thinking. Clearly, it doesn’t.

This gives rise to the second question: Why do we keep coming back to magic?

And that’s a question I can’t fully answer. But to my mind, a good question is always better than delusion, particularly if it helps us understand ourselves better. The historical evidence suggests a few things, at least.

The best things in life are free

As the song goes, the best things in life are free. But the best things are also notoriously difficult to control. Modern science may have helped us live longer but it hasn’t made illness and death any less inevitable. It certainly hasn’t made it possible to make ourselves more wealthy, desirable, charismatic, intelligent or successful in love.

From one perspective, love magic is biological. We are biologically programmed to try anything that might help us reproduce ourselves. Skepticism would just get in the way of that. Hope, on the other hand, keeps us creatively trying things out and doing whatever it takes: The perfect clothes, the right music, giving flowers, perfume, beautiful words, … or magic.

From another perspective, as Malinowski suggested, magic springs from human qualities that we all value very highly: Optimism, hope and creativeness. Where would we be without those? If our ancestors only stuck to the tried and true, things they knew would not fail, we’d still be in the trees. We’d certainly have no love songs.

If magical thinking got us here, then maybe we shouldn’t worry too much about it.

This is a corrected version of a story originally published Feb. 13, 2018. The earlier story incorrectly identified the author of the 1948 book, “Magic, Science and Religion” as Stanislaw Malinowski. The author is Bronislaw Malinowski.

Author: Frank Klaassen: Associate Professor of History, University of Saskatchewan

Credit link: https://theconversation.com/the-magic-of-love-and-sex-91749<img src="https://counter.theconversation.com/content/91749/count.gif?distributor=republish-lightbox-advanced" alt="The Conversation" width="1" height="1" />

The article was first published by The Conversation (http://www.theconversation.com) and is republished with permission granted to www.oasesnews.com