Don Drummond, Queen's University, Ontario and Duncan Sinclair, Queen's University, Ontario

Canada’s population is rapidly aging, but is it aging well? In our November 2020 report “Ageing Well,” we found both good and bad news.

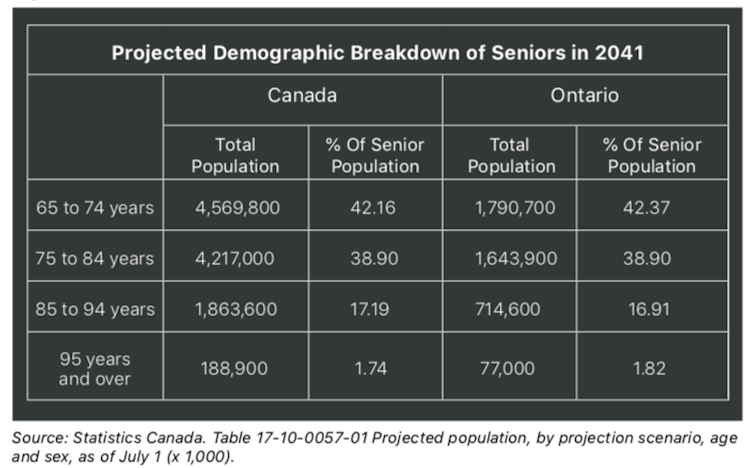

The good is that Canadians are living longer. Back when medicare became the backbone of our health-care system about 60 years ago, seniors made up 7.6 per cent of the population. They now constitute 17.5 per cent and will be almost 25 per cent in 2041 — 10.8 million people whose average age will be in the low 80s just over 20 years from now. They should all age happily and well.

The bad news is that they don’t want to live in old-folks’ homes where current policy tends to put them. Also, ensuring they have the support services they need to age well will require major changes to how, where and by whom those services are provided, and change can be difficult to implement in any dimension of health care.

Providing those services will also cost each of us more, both individually and as taxpayers. Canada is heading into a less robust economic period, in part due to the need to pay down our COVID-19 debt — and we may be hard-pressed to pay that bill.

Long-term care (LTC) in all Canadian provinces has become more or less synonymous with the care and services provided in nursing and retirement homes owned and operated by private for-profit and not-for-profit companies, charities and municipalities.

Relative to many other developed countries, the foundation of Canadian policy to meet the needs of the elderly is aptly described as “warehousing,” housing designed primarily to optimize the efficient provision of nursing and personal care. Most if not all such care homes also do their best to provide other services too, but it’s fair to say that meeting seniors’ social and recreational needs plays second fiddle to meeting their personal and health-care needs.

What seniors need to age well

What do our seniors want? It’s not to live in an institution, the possible exception being the poor soul who has lingered too long in an alternative level of care bed: no longer in need of intensive in-hospital care but still requiring some services not readily available in most Canadian provinces other than LTC facilities.

To age well, seniors have four interrelated needs:

Housing appropriate to their needs and preferences. For most, their strong preference is for the family home in the same community with familiar neighbours, surroundings and amenities. They want to age in place and remain there as long as they possibly can, receiving the care and support services they need at home.

Flexible health and personal care, and household support appropriate for each individual or elderly couple as their needs wax and wane. These needs usually increase as they age, but not always. Evidence shows clearly that if the well-being of seniors is supported in all its dimensions, and if the delivery of services begins “upstream” at the first sign of trouble, the prevention and slowing — if not reversing — of the onset and progression of both dementia and other manifestations of frailty can be achieved.

Socialization is another of the four key needs of aging well, a need met best by enabling seniors to remain in their own communities with their families, friends and neighbours and recognizing their familiarity with the range of the services their community provides.

Meeting seniors’ lifestyle and/or recreational needs is also vital to aging well, especially as they’re integrated with the individual’s or couple’s social needs. Sadly, data indicate that seniors, like too many other Canadians in our contemporary online society, are succumbing to “couch potato” tendencies that erode the beneficial effects both of social interactions and regular exercise.

With respect to the money we spend to help our seniors age well, Canada is an outlier among developed countries. We spend less overall (in 2017, 1.3 per cent of Canada’s GDP) on long-term continuing care and services; only Spain spends less (0.7 per cent). Implementing the likely recommendations to come out of several provincial COVID-related LTC reviews will likely take us to the OECD average, or slightly above it.

However, our outlier status will remain accentuated by our remarkably imbalanced spending of $1 on home care for every $6 spent on institutional LTC. Most others spend roughly equal amounts, and those most highly regarded for the high quality and happy outcomes of enabling seniors to age well — Denmark and the Netherlands, for example — do the reverse. They spend more on home and community services than on institutional care.

Four factors that must change

Given our foreseeable demographic and economic circumstances, continuing with the same policy choices defies comprehension.

First, as COVID-19 has clearly demonstrated, care homes are dangerous places in which infectious diseases can spread easily; some 80 per cent of deaths in the first wave in Canada were in LTC homes.

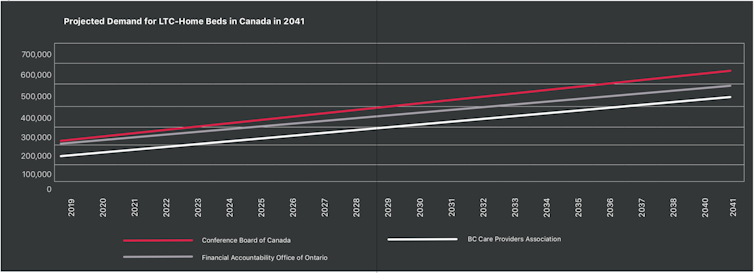

Second, given the increased number and advancing age of the baby boomer generation, continuing with our warehousing propensity is doomed to failure. The number of care-home beds that would be required is simply beyond what we could afford. This is compounded by the fact that such beds were already subject to long waiting lists even before their post-COVID-19 downsizing to eliminate shared rooms and washrooms.

Third, to reiterate, few seniors want to live in long-term care, preferring strongly to remain in their own homes and communities or in various alternative forms of communal housing in which they have access to home and community services.

And fourth, the cost of institutional accommodation and care — to residents, their families and the public purse — exceeds by far what it would cost to provide an extended range of seniors’ needs through beefed-up home and community support services. That would be expensive too, but it’s an approach to helping our seniors age well that our country could afford.

Substantial change to Canada’s long-term support service systems is long overdue. It’s time to get at it.![]()

Don Drummond, Stauffer-Dunning Fellow in Global Public Policy and Adjunct Professor at the School of Policy Studies, Queen's University, Ontario and Duncan Sinclair, Professor of Health Services and Policy Research, Queen's University, Ontario

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.