Poco Kernsmith, Wayne State University; Erin B. Comartin, Wayne State University, and Sheryl Kubiak, Wayne State University

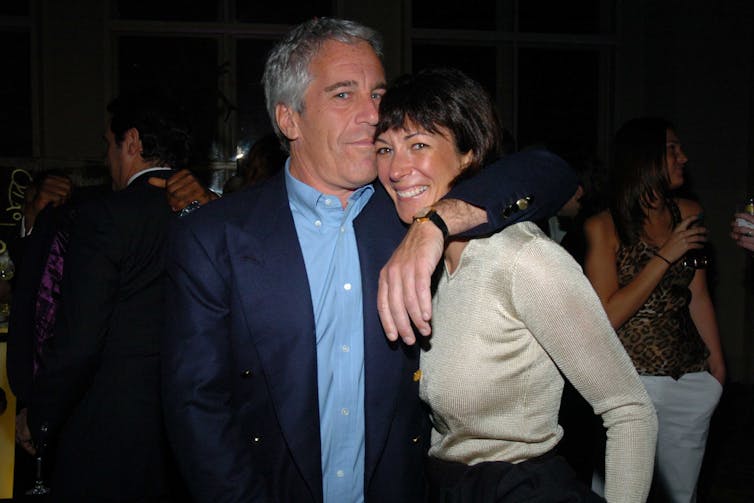

British socialite Ghislaine Maxwell has been convicted for her role in luring and grooming girls to be sexually abused by the American financier Jeffrey Epstein.

In a court in lower Manhattan, Maxwell – a close friend of Epstein’s – was found guilty of five counts including sex trafficking a minor. She now faces a maximum sentence of 65 years behind bars.

The verdict comes more than two years after Epstein took his own life while in jail awaiting trial on charges including conspiracy to traffic underage girls for sex.

Maxwell’s trial provided an opportunity for victims of Epstein and Maxwell to give court testimony about the abuse they experienced. The case also highlights the importance of understanding sex offenses perpetrated by women.

Maxwell was convicted on charges including trafficking a minor for sexual purposes and conspiracy to transport an individual under the age of 17 across state lines with the intent of engaging in illegal sexual activity. To date, Maxwell is the only person to stand trial for the abuse of these girls.

We have studied women who have been convicted of sexual assault, abuse and human trafficking, as well as public attitudes toward sex offenders. Our research, and that of others, shows the similarities and differences between male and female sexual offenders.

How common are sex offense charges against women?

The majority of sex offenders are believed to be male. Charges lodged against women may include sexual abuse of children but often involve grooming or trafficking girls without engaging in the act of sexually abusing the child.

Estimates of the proportion of sexual abuse committed by women range from 1% when based on conviction rates to 40%, according to some surveys of people who are survivors of sexual abuse.

But arrest and conviction rates may underrepresent the actual number of female sex offenders because those who have been assaulted by a woman are less likely to report the abuse. It is believed this results from social norms that define sexual assault as being perpetrated by men, and rape myths that say boys should always want sex or could not be overpowered by a woman.

Female offenders are also less likely than men to be arrested and convicted. And, if they are convicted, they typically receive shorter sentences than male offenders.

Women as co-offenders

Women who commit sexual offenses differ from male offenders in many ways. Female offenders are more likely to offend in a caregiving role, such as babysitter, teacher, parent or guardian of the victim.

The victims of female offenders are often younger than those of male offenders, and female offenders are equally likely to offend against female and male victims.

However, the most striking difference is that female offenders are six times more likely than male offenders to have a co-offender, meaning two or more people participate in the abuse of the same victim.

Elements of this profile of a female offender fit what we now know of Maxwell. She participated with Epstein, a male co-offender several years her senior. In court, victims portrayed Maxwell as someone whom they initiallybelieved they could trust, viewing her like a friend or an older sister.

In testimony and interviews, Epstein’s victims report that the presence of Maxwell before and during the assaults made them feel that they were safe. The victims questioned their feelings that what was happening was actually rape or sexual assault. They report ignoring red flags because they felt that if Maxwell acted as if the situation were normal, they must be wrong in feeling violated.

Maxwell a ‘sophisticated predator’

Research shows that women may be involved by recruiting and manipulating the victims into dangerous situations and helping to provide a sense of safety for the victims. They may coerce or manipulate the victim, or behave in sexually abusive ways in front of, or at the same time as, the male abuser.

Victims of Epstein have said that the financier’s female co-offenders – including Maxwell – engaged in all of these forms of abuse.

In the Maxwell trial, the court heard how she pressured victims into sexual acts with Epstein, would talk to the girls about sex and sexually touch the victims.

Women co-offend for many reasons. Some may abuse victims for reasons similar to male offenders – for example, to gain power, to retaliate against someone or because of sexual deviance.

However, many are coerced or forced by the male co-offender.

During the closing argument in Maxwell’s trial, both these pictures of the female sexual offender were presented. Assistant U.S. Attorney Alison Moe characterized Maxwell as a “sophisticated predator who knew exactly what she was doing.” “She ran the same playbook again and again and again,” Moe said.

Defense attorney Laura Menninger framed Maxwell as a victim of Epstein’s manipulation, stating, “It was clear Epstein was a manipulator of everyone around him. Someone like Jeffrey Epstein is always trying to control the people around them – use his position to manipulate people and play them off against one another.”

What should be done?

If there is one positive outcome of the high-profile trial of Maxwell, it is that it has shown that perpetrators of sexual abuse can be women.

In our experience, many sexual violence prevention programs, materials and public service announcements universally depict perpetrators as men only. This not only teaches children to fear men but also may make potential victims more likely to trust a woman, even when her behavior is coercive, manipulative or abusive.

Prevention programs can be designed to specifically address women as potential perpetrators to prevent abuses, such as those alleged in the Maxwell case.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on Sept. 24, 2019 .![]()

Poco Kernsmith, Professor of Social Work, Wayne State University; Erin B. Comartin, Assistant Professor of Social Work, Wayne State University, and Sheryl Kubiak, Dean and Professor of Social Work, Wayne State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.