Gaelle Planchenault, Simon Fraser University

The visual effects in Marvel’s Dr. Strange in the Multiverse of Madness don’t disappoint, but the treatment of the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) lead female villain does.

Wanda Maximoff (Elizabeth Olsen) hasn’t been given much positive character development. In contrast to Marvel’s notorious villains, Wanda has no grand design, no desire to rule or destroy humanity. Her goal is limited to her self-created picture of domestic happiness: she fights to reunite with her two sons.

Such treatment is an illustration of the separate spheres’ sexist doctrine: to men, the world is a stage, while women must limit themselves to the private sanctum of the house.

But more problematic is the representation of one particular aspect of Wanda’s character: her anger. In the film, references to mythological and popular culture figures of female anger are allusions to stereotypical expectations associated with women’s conduct.

Female demonstrations of anger

Mainstream media images contribute to drawing emotional norms of what is considered appropriate behaviour. Female demonstrations of

.Such rhetoric plays an important part in maintaining a gendered social order. By preventing agency, it also contributes to gate-keeping positions of power.

Wanda appeared in several instalments of the MCU franchise where her character experienced important changes: first as a villain, then as a rehabilitated ally to the Avengers. She then became the complex character of the WandaVision mini-series.

Alter-ego: The Scarlet Witch

Wanda’s rage fuels her actions and gives her the will to kill anyone who stands between her and her sons. And killing she does throughout the film — superheroes and civilians alike. With the aid of her alter ego, the Scarlet Witch, and the control of the Darkhold, she seems unstoppable.

This anger-fuelled behaviour is depicted as stereotypical female anger: over-emotional and irrational.

The lack of rationality in Wanda’s acts is exposed in her second encounter with Dr. Strange (Benedict Cumberbatch) when he tries to bring her to reason: an offer she rejects by stating “This is me being reasonable.” She then draws a trail of death in Kamar-Taj.

A modern Medusa

In this same scene, Wanda leaves bodies literally petrified: a reminder of the fate of Medusa’s victims, the female monster of Greek mythology that turned to stone the men who dared to look into her eyes.

As noted by professor of English Elizabeth Johnson, “Medusa has haunted western imagination, materializing whenever male authority feels threatened by female agency.”

Wanda wears her anger on her sleeve, or rather in her hands, from which she shoots lethal balls of fire, an extension of her unbridled emotion. This may strike viewers as an allusion to the powerful fairy Maleficent who in Disney’s 2014 film commands the growing of thorns from the palm of her hands.

As writer Hephzibah Anderson suggests, such thorns are another powerful symbol of woman’s rage towards men who try to breach boundaries too hastily.

Blood rage

In another key scene, Wanda proceeds to systematically massacre the Avengers and appears dressed in a white shirt covered in blood, her face stained by red streaks. Viewers are unsure whose blood it is, and no explanation is given.

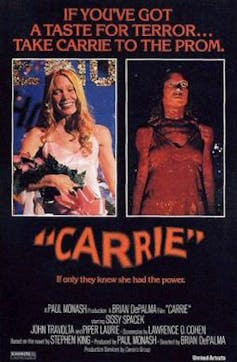

This scene refers to the cult horror film Carrie (1976) where Sissy Spacek’s character’s power and her subsequent killing spree is triggered by her menses and the shaming that she experiences as a result.

This is a reminder that menstrual blood has long been associated with female irrational anger, but also that female rage has often been pathologized, sometimes linked to hysteria.

Anger: Noble or stigmatized?

Since the foundation of the western heroic mythology — and as far back as Homer’s Iliad (that begins with Achilles’ righteous anger) — literary tradition has given men the right to make productive use of their anger while negatively representing the angry woman.

When expressed by the powerful, emotions are received as appropriate, noble even. The same emotions expressed by minoritized groups are stigmatized. Women’s anger can also be racialized: for example, research about the reactions to Black women’s expressions of anger at work finds that “expressions of emotion are evaluated differently depending on demographics” and that racial stereotypes affect how people perceive anger in Black women.

As cultural critic Roxane Gay asks: “Who gets to be angry?”

Victims of oppression feel pressurized to let go of their anger to appease discussions. According to professor of political and social theory, Amia Srinivasan, this is injustice through the policing of emotions.

Dr. Strange seems to recognize an emotional double standard at the beginning of the film when Wanda makes the following comment to Dr. Strange:

“You break the rules and become a hero? I do it and become the enemy. That doesn’t seem fair.”

Yet even when there is no doubt that the cause of their emotion may be valid (rape for Medusa, while Wanda was forced to murder her own partner), victims’ anger is depicted as a threat to social peace.

Reclaiming feminine power

For centuries, witch hunts realized male desire to control women’s bodies and social role. The function of witches is today defended by feminists who reclaim feminine power and women’s political role.

But the MCU franchise’s representation of the female villain clearly ignores this dimension.

Spectators might wonder whether the scarlet linked to Wanda’s character refers to the blood that she sheds, to the colour associated with rage — or to the stigma that was attached to the letter in the classic 19th-century novel by Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter.

Disgrace befalls the woman who endeavours to carve her own path.![]()

Gaelle Planchenault, Associate Professor of French Media, Culture, and Applied Linguistics, Simon Fraser University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.