With Ontario Premier Doug Ford handing the province’s municipalities the right to prohibit retail cannabis stores in their communities, he has displayed a populist penchant for municipal autonomy.

But prohibiting cannabis retail stores, as Richmond Hill and Markham have done, might not be the best way to avoid the problems many associate with cannabis.

I say this because the idea that a municipality could ban the sale of intoxicants within their boundaries is older than Canada itself, is well-tested and has almost always been fraught with problems.

An 1864 law allowed municipalities to vote themselves “dry” by popular referendum, permitting a simple majority of electors to vote to end the retail sale (but not the manufacture) of alcohol in their communities.

Many dry communities saw little improvement. Others saw increased drunkenness.

And so many communities repealed the local option as soon as they could.

Liquor licensing

After Confederation, other alternatives to deal with drunkenness emerged. In 1876, the Ontario government took over liquor licensing. Although flawed, the law significantly decreased drunkenness in many communities.

But the temperance folks wanted Prohibition, and in 1878 the federal Liberal government passed the Canada Temperance Act. Under this improved version of the 1864 legislation, local options could be implemented at a county or city level, again by a simple majority.

Manufacturing could continue in dry communities, but it could not be sold there. Nothing, however, prohibited residents of dry communities, if they could afford it, from ordering booze from outside their town.

By 1887, 25 counties in Ontario were dry; two years later all dry counties in the province had repealed the Canada Temperance Act.

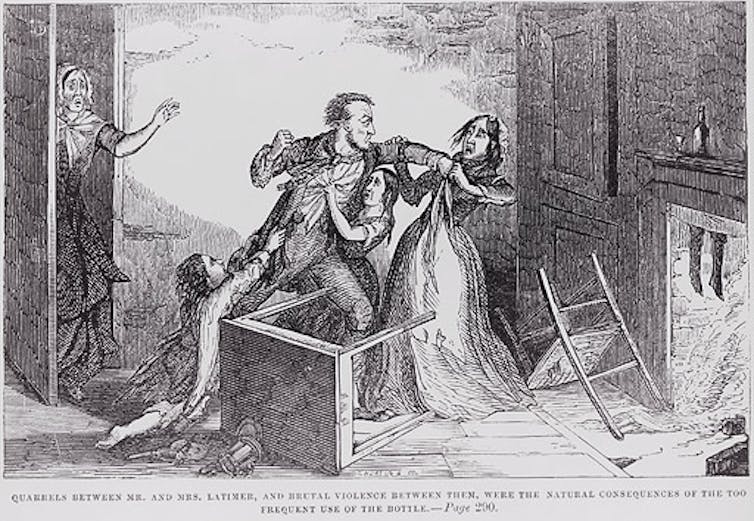

Clearly, the temperance law was a failure. At the Royal Commission on the Liquor Trafficthat toured Ontario in 1893-94, many witnesses —ranging from judges and priests to temperance supporters and liquor dealers —described how drunkenness continued in dry areas. Brewers and distillers provided their account books to show how productivity actually increased with large orders from dry counties pouring in.

Many described the various ways that the local option law was circumvented and how drinking often seemed to get worse.

People who might in the past have had a glass of lager in a tavern turned to whisky because it was stronger and more easily portable. Others ordered a barrel of beer to distribute from the back of a wagon. Some told how children made a game of getting their hands on whisky that had been secreted for later use, turning up drunk and sick. Horror stories abounded, and although there was doubtless exaggeration, many of the witnesses were reliable and respectable and provided their testimony under oath.

The local option a nuisance, not a deterrent

The local option saw a resurgence after the provincial government passed a law in the early 1890s allowing areas smaller than a county to vote themselves dry, but they required a higher proportion of support than a simple majority.

This was an attempt to ensure that only places with strong support for Prohibition could become dry. Many local option laws continued well into the 20th century, notably in places like Toronto’s Junction neighbourhood. But with the car replacing horse power, and the local option being implemented in small communities often adjacent to wet ones, it became more of an inconvenience than a deterrent to drinking.

The local option generally failed for several reasons.

First, booze was profitable and vendors in nearby towns could easily get it to thirsty customers in dry areas. Second, the requirement of only a simple majority to pass the law meant that a large portion of the community would look for ways around the law. Third, this system favoured the rich who could afford to have whole kegs of beer or whisky shipped to them, or could travel to other towns to buy their booze.

It disadvantaged the poor, whose finances and mobility were strictly limited. It became, as commentators argued, “class legislation” discriminating against the poor while only inconveniencing the rich.

With all these problems, even many who supported Prohibition argued that a well-controlled licensing system was preferable.

Cause for pause

This experience with the local option in Ontario should give today’s municipal governments pause before following the path of Richmond Hill and Markham.

When you institute local prohibition, you encourage illegality and inequity.

The product you’re trying to restrict becomes more lucrative. This nurtures the very black market that the Cannabis Act is trying to squash.

Some people will not be able to get legal cannabis. The planned internet ordering system is convenient for people with credit cards and access to computers. It is not as convenient for poorer people.

So some people will have to find other ways to get their hands on cannabis, thereby encouraging the continuation of illegal sales. (Let’s save the elitist debate about whether poor people should be smoking pot for another day.) This could be dangerous, given the rise of synthetic cannabis and weed containing dangerous contaminants that wouldn’t normally be available through legal distribution channels.

Unless a vast proportion of residents in a community support such restrictions, such prohibition could encourage more illegality, more excess and more access to cannabis for those whom the law is designed to protect. Mayors who say that they’ve heard from people who don’t want cannabis shops in their town need to ask themselves if these voices are representative, or just loud.

Banning cannabis retail sales could cause more profound problems than it solves.

Author:Associate Professor, Medical History, Department of Health Sciences, Brock University

Credit link:https://theconversation.com/want-cannabis-stores-banned-in-your-town-read-this-first-101729<iframe src="https://counter.theconversation.com/content/101729/count.gif?distributor=republish-lightbox-advanced" width="1" height="1"></iframe>