Weed, spliff, cannabis, joint, blunt, Mary Jane, ganja, reefer, marijuana, pot: no matter what you call it, it is almost legal in Canada. Many will benefit from the new right to grow, sell or smoke legally and freely.

Before we celebrate, let’s take a moment to remember the Black and Indigenous peoples who have been overrepresented in Canada’s cannabis-related arrests, despite similar rates of cannabis use across racial groups. According to a 2017 Toronto Star report:

“Black people with no history of criminal convictions have been three times more likely to be arrested by Toronto police for possession of small amounts of marijuana than white people with similar backgrounds…”

A Vice report filed by Rachel Browne looked at statistics from 2015-17 and found that:

“Indigenous people in Regina were nearly nine times more likely to get arrested for cannabis possession than white people during that time period.”

The Cannabis Act (Bill C–45), informed by the recommendations of the Task Force on Cannabis, creates a legal framework for “controlling the production, distribution, sale and possession of cannabis in Canada.”

The act, however, does not discuss cannabis amnesty. Cannabis amnesty is the clearing or turning over of previous convictions of cannabis “crimes” that occurred before the legislation took effect.

Cannabis has a long history of being used to criminalize African, Indigenous and racialized peoples in Canada and globally. The lack of redress in Canada’s Bill C-45 for those convicted of marijuana charges indicates Canada’s continuation of these racist policies and processes.

While there are some critical discussions among African or Black scholars, lawyers and activists, the history of who has been criminalized has largely been ignored or silenced in the current legalization debates.

A continuum of colonial tragedies

Despite the absence of race in the legal debates, some media and academics have linked racism and the decriminalization of cannabis in Canada.

Robyn Maynard’s book Policing Black Lives: State Violence in Canada from Slavery to Presenteloquently discusses the historical and current realities of anti-Black racism (and Black resistance) through state-sanctioned violence. Maynard connects drug incarcerations with child incarcerations (in the form of Children Aids Society apprehensions) and other racist systemic practices that continue to harm mostly African and Indigenous families.

In addition to the Toronto Star and Vice reports, articles in the National Post and the Guardian question why the new legislation does not address past and more recent marijuana convictions and criminalization.

Other news stories that link racism to the criminalization of cannabis have come out of the CBC, Macleans and Now. But much more research and discussion about the impacts of both the criminalization and the decriminalization of cannabis on Black and Indigenous communities is needed.

There has been a deliberate campaign to criminalize racialized groups in Canada and the United States, and the criminalization of cannabis use has been part of this.

Many members of the Black and Indigenous communities feel outrage, anger and distress at the historically racist legislation. They now feel excluded from its possible resolution.

How long shall they kill our profits?

Despite a few good articles, the news media has mostly focused on the cannabis market.

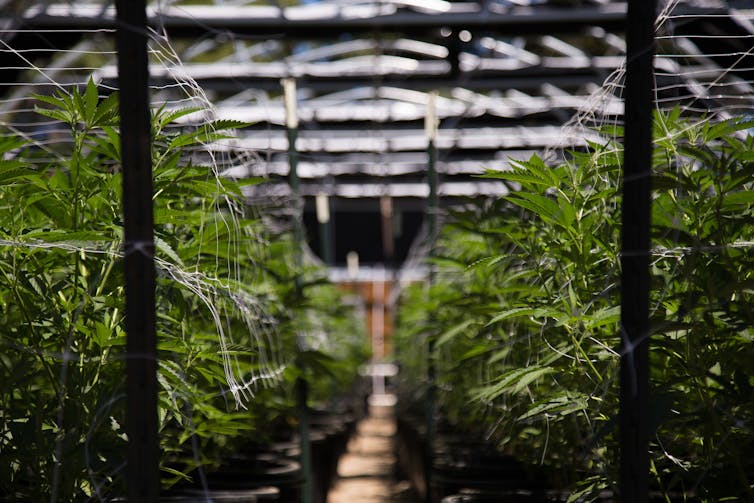

Cannabis is a plant that has been used globally for thousands of years for spiritual, recreational and medicinal purposes. In many communities, cannabis is a cultural marker. For example, Rastafarian communities use cannabis in spiritual ceremonies.

The Cannabis Act does not specifically discuss the market possibilities of this gentrified industry, but the links between white male elites and the business of cannabis can already be seen. Now reports that while there are exceptions, “almost all of the country’s 80-plus licensed producers (LPs) are run by white men” and only “five per cent of board members of publicly traded weed companies in Canada are female.”

By focusing mainly on the money to be made from the “new legitimized” growers and sellers, these stories of potential success ignore the permeating racist ideology, structures and practices that were created to systematically steal resources (including people) from Indigenous communities globally. In the conversations about money, there are few discussions about reparations for past violence and diminished opportunities.

Evidence from the U.S. shows that in states where cannabis is legal, racialized folks continue to be arrested at higher rates than whites for weed possession.

Therefore, racialized people are still criminalized for cannabis, punished and isolated from their families and communities, leaving opportunities for big cannabis business in the hands of white elites.

Why Canada banned pot

The ban on drugs, including cannabis, in the early 20th century has links to racism and curtailed immigration. For example, the 1908 Opium Act and the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act are both connected to anti-Asian sentiments, under the guise that opium would be brought by Chinese immigrants to “Canadian (white) youth.”

Emily Murphy’s 1922 book, The Black Candle helped to connect the fear of “the other” to cannabis. Soon after her book was published, cannabis was added to the restricted list of drugs in the 1923 Opium and Narcotic Drug Act. That act and the later Narcotics Control Act of 1961 led to marijuana convictions and incarcerations.

The Canadian state was built on Indigenous genocide and apartheid, sanctioned by the ruthless Indian Act and the viciousness of the “enslavement of African peoples” whereby enslavement “was a legal instrument that helped fuel colonial economic enterprise.” This history shaped the environment where Black and Indigenous peoples were deemed to be criminalized.

Marijuana legalized today: Racism here to stay?

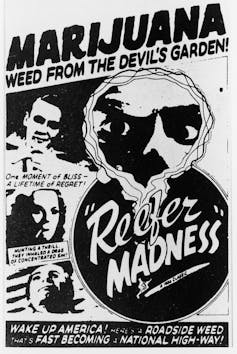

Similarly, in the U.S., Mexican and Black people were blamed for cannabis use. These racist ideas were popularized by a 1936 propaganda film Reefer Madness, which spread racialized notions of the harm Black and Mexican users had on “good (white) folks.” The passage of the Boggs Act in the U.S. in 1952 set mandatory sentences for marijuana convictions.

For the cannabis movement to be truly effective, it must address amnesty, anti-Black racism and other intersectional violence inherent in our justice system. But history has taught us that colonial violence is insidious and continuous.

The lack of accessible race-based data on the criminalization of marijuana in Canada supports the theory that discussions of racial surveillance, profiling, carding and arrests that target Black and Indigenous communities have been silenced.

The redress of marijuana-related convictions on African/Black and Indigenous peoples are not emphasized in Bill C-45. Instead, the Cannabis Act expansively outlines the behaviour that is prohibited and punishable under the new legislation.

This emphasis ensures that the impact of cannabis amnesty will be limited and that Black, racialized and Indigenous communities will continue to face criminalization in Canada and globally, proving that old colonial rules, new elites and continuing violence still sanction the selling and use of cannabis.

We continue, however hopeless it sometimes feels, with the weight of thousands of ancestors behind us, resisting, persisting and demanding — for real freedom. This struggle includes the fight for amnesty for “crimes” from which others can now freely economically and socially benefit.

Author: Roberta K. Timothy Assistant Lecturer Global Health, Ethics and Human Rights School of Health, York University, Canada

Credit link:https://theconversation.com/as-cannabis-is-legalized-lets-remember-amnesty-103419<iframe src="https://counter.theconversation.com/content/103419/count.gif?distributor=republish-lightbox-advanced" width="1" height="1"></iframe>