Nancy Kang, University of Manitoba

In Mules and Men (1935), anthropologist, creative writer and Harlem Renaissance upstart Zora Neale Hurston relays the evocative folktale “Why the Sister in Black Works Hardest.” Fatigued after the work of Creation, God casts a massive bundle onto the earth. Intrigued by the mysterious object, a white Southern woman during the antebellum era asks her husband to retrieve it. Reluctant to tote the load himself, the master instructs a slave to fetch it.

Soon wearied of the task, the slave then commands his wife to shoulder the burden. She does so, excited at the prospect of exploring the contents. When she opens the package, however, what leaps out at her and Black women for all posterity is none other than hard work.

African American women writers have tackled the hard work of representing a diverse spectrum of lived and imagined experiences, including and especially their own. This labour occurs against the backdrop of centuries-long struggles with racist oppression and gender-based violence, including — but not limited to — slavery’s culture of endemic rape, forced or interrupted motherhood, infanticide, concubinage, fractured families and egregious physical and mental abuse.

Hard work as groundwork

Renowned abolitionist Frederick Douglass recalls in his 1845 slave narrative how witnessing the serial whippings of his Aunt Hester impacted him “with awful force.” He explains, “it was the blood-stained gate, the entrance to the hell of slavery, through which I was about to pass. It was a most terrible spectacle.”

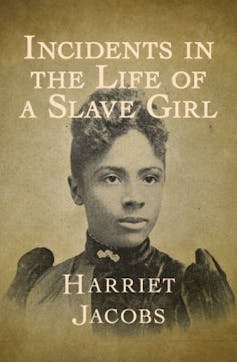

These ordeals also emerge in slave narratives by women. Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861) emphasizes such travails. A target of relentless sexual harassment by her much-older master, Jacobs laments, “When they told me my new-born babe was a girl, my heart was heavier than it had ever been before. Slavery is terrible for men; but it is far more terrible for women.”

Once emancipated, African American women still faced staggering impediments when pursuing educational, entrepreneurial and employment opportunities. Political participation meant restrictions on voting rights both as women and as people of colour. Racist caricatures impugned everything from a woman’s intelligence and moral capacity to her skin color, texture of hair and body shape. Stereotypes like the docile Mammy, the Tragic Mulatta, the clownish Topsy, the oversexed Jezebel, the greedy Welfare Queen, the amoral Hoodrat and the Mad Black Woman (still prevalent today) remain testaments to a history of disrespect and erasure.

Hurston’s tale symbolizes the enduring social struggles Black women have faced living in what feminist critic bell hooks has termed white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.

In addition to influential autobiographers like Maya Angelou, dramatists like Lorraine Hansberry and poets like Gwendolyn Brooks, fiction writers have consistently demonstrated how imaginative art can simultaneously inform, persuade, entertain, catalyze social change and address individual as well as collective concerns.

Here is a short list of pivotal texts by African American women from the past century. These writers are but a small sample of the artists and intellectuals whose output resisted the force of what contemporary feminist critic Moya Bailey has termed misogynoir, or the corrosive fusion of anti-Blackness and misogyny prevalent in popular culture today. These women have completed the groundwork — and hard work — of envisioning a more just, inclusive society going forward.

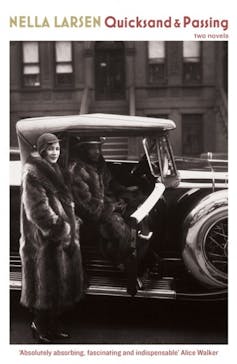

Quicksand (1928) and Passing (1929) by Nella Larsen

These novellas follow mixed-race women whose uneasy status on the colour line (including the lure of passing as white) complicates their lives in dangerous, even fatal ways. Passing is revolutionary for its depiction of homoerotic tension between two upper-middle-class Black women. Quicksand offers insight into the exoticization of African American women abroad and the contest between art and domesticity as viable avenues for a fulfilling life.

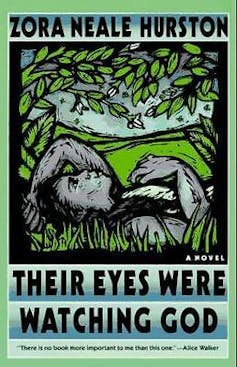

Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937) by Zora Neale Hurston

This story is the lyrical account of thrice-married Janie Crawford who finds a mature vision of love and fulfillment amid incessant gossip and a difficult family history. The all-Black township of Eatonville, Fla., and the rich “muck” of the Everglades contribute to a portrait of community health, daily striving and resolute self-awareness.

The Street (1946) by Ann Petry

This social realist novel follows single mother Lutie Johnson as she attempts to make a life for her young son in a predatory urban space. Weathering sexism, racism, classism, poverty and intense personal frustration, Lutie attempts to resist the brutality of the environment that gives the novel its loaded name.

The Bluest Eye (1970) by Toni Morrison

This book is a searing portrait of a young girl’s coming-of-age and eventual undoing in the years following the Great Depression. Tumultuous family dynamics, psychological trauma and incest, the quest for compassion and self-love, and the toxic myth of Black ugliness coalesce in this first novel by the Nobel Laureate and author of neo-slave narrative Beloved (1987).

Kindred (1979) by Octavia Butler

Oscillating between the 1970s and the early 19th century, this science fiction odyssey (re)connects a contemporary Black woman writer and her white husband with her ancestors on a Maryland plantation. The novel is buoyed up by the dramatic tension of time travel and the juxtaposition of the pre-civil War Antebellum-era with Civil Rights-era racial attitudes, including those about interracial love and allyship.

The Women of Brewster Place (1982) by Gloria Naylor

Structured like a narrative quilt, these interconnected experiences of seven women span different generations, professions, class backgrounds and understandings of their place in the world. The eroded apartment complex that links them is the backdrop for unbearable pain as well as the promise of transformation and reconciliation.

The Color Purple (1982) by Alice Walker

A tale of two sisters, Celie and Nettie, this novel constellates their love and longing via letters and imagined conversations across the Atlantic. Unsparing in its critique of domestic violence and toxic masculinity, yet tender in its treatment of various human weaknesses, the novel underscores Black women’s need for self-regard and mutual care. Not only are these acts revolutionary, but they also offer a glimpse of the divine.![]()

Nancy Kang, Assistant Professor of Women’s and Gender Studies and Canada Research Chair in Transnational Feminisms and Gender-Based Violence, University of Manitoba

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.