Joseph McQuade, University of Toronto

We are currently experiencing the worst environmental crisis in human history, including a “biological annihilation” of wildlife and dire risks for the future of human civilization.

The scale of that environmental devastation has increased drastically in recent years. Mostly to blame are anthropogenic, or human-generated factors, including the burning of fossil fuels like coal and oil.

Other industries like gem and mineral mining also destroy the world’s ecological sustainability, leading to deforestation and the destruction of natural habitats. Much of this traumatic exploitation of natural resources traces its origins to early colonialism.

Colonialists saw “new” territories as places with unlimited resources to exploit, with little consideration for the long-term impacts. They exploited what they considered to be an “unending frontier” at the service of early modern state-making and capitalist development.

To understand our current ecological catastrophe, described as “a world of worsening food shortages and wildfires, and a mass die-off of coral reefs as soon as 2040,” we need to look at the role of colonialism at its roots.

This exploration is not a debate over whether colonialism was “good” or “bad”. Instead, it is about understanding how this global process helped create the world we currently inhabit.

Clear-cutting rainforests for industrial rubber

Since the 15th century, the Indian Ocean has been the site of global trade. Colonialism built upon local economic systems but also profoundly built up and shaped many of the massive industries and processes that are currently at play in the region.

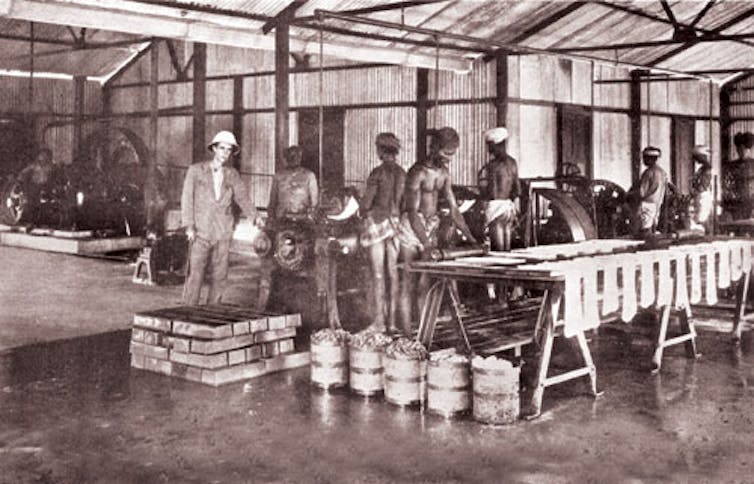

For example, British colonialists transformed the Malay peninsula into a plantation economy to meet the needs of industrial Britain and America. This included the expanding demand for cheap rubber during the industrial revolution.

Exploitative colonial policies in Singapore and the peninsula limited the economic options of poor Malays, Indians and Chinese. These workers were increasingly forced to clear cut vast swathes of rainforest to literally carve out a living for themselves at the expense of local ecosystems.

Meanwhile, more than half a century after the end of colonial rule in the Malay peninsula, the over-exploitation of local resources through extensive logging continues apace. Once numerous, Malayan tigers are now classified as a critically endangered species due, in part, to habitat loss from logging and road development.

Deforestation in Malaysian Borneo also continues to accelerate, mainly due to the ongoing global demand for palm oil and lumber.

Exporting for global markets

In Myanmar (formerly Burma), trade in raw commodities goes back centuries. Under colonial rule, the export of minerals, timber and opium expanded enormously, placing unprecedented strain on local resources.

The integration of regions north of the Irrawaddy River basin into the Burmese colonial state drastically increased economic integration between upland areas rich in natural resources and larger flows of European and Chinese capital.

Today, despite generating billions of dollars in revenue, these regions are some of the poorest in the country and are home to widespread human rights abuses and environmental disasters.

Extracting Africa’s gemstones and minerals

The human cost of the diamond trade in West and South Africa is relatively well-known. Less known are the devastating effects on Africa’s environment that the stripping of natural resources such as diamonds, ivory, bauxite, oil, timber and minerals has produced. This mining serves a global demand for these minerals and gems.

The intensive mining operations required to deliver diamonds and other precious stones or minerals to world markets degrades the land, reduces air quality and pollutes local water sources. The result is an overall loss of biodiversity and significant environmental impacts on human health.

From 1867 to 1871, exploratory digging along the Vaal, Harts and Orange rivers in South Africa prompted a large-scale diamond rush that saw a massive influx of miners and speculators pour into the region in search of riches. By 1888, the diamond industry in South Africa had transformed into a monopoly, with De Beers Consolidated Mines becoming the sole producer.

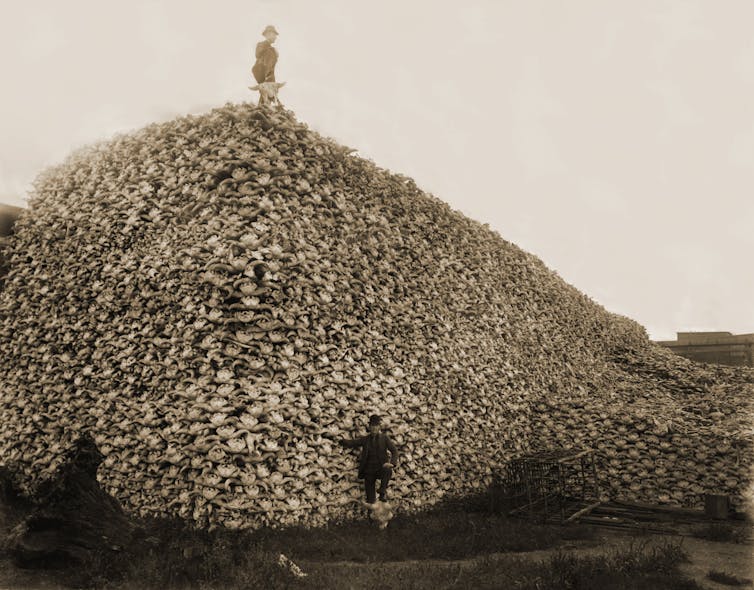

Around the same time, miners in nearby Witwatersrand discovered the world’s largest gold fields, fuelling the spread of lucrative new mining industries. As European powers carved up the continent in the so-called “scramble for Africa” during the late 19th century, commercial exports came to replace slavery as the primary economic motivation for direct colonial occupation.

New transportation technologies and economic growth fuelled by the industrial revolution created a global demand for African exports, including gemstones and minerals that required extensive mining operations to extract.

From 1930 to 1961, the diamond industry in Sierra Leone played a crucial role in shaping and defining colonial governmental strategies and scientific expertise throughout the region.

Nearby Liberia was never formally colonized and was established as a homeland for freed African-American slaves. But American slaveholders and politicians saw the republic primarily as a solution to limit the “corrupting influence” of freed slaves on American society.

To “help” Liberia get out of debt to Britain, the U.S.-based Firestone Tire and Rubber Company extended a $5-million loan in 1926 in exchange for a 99-year lease on a million acres of land to be used for rubber plantations. This loan was the beginning of direct economic control over Liberian affairs.

Unequal power relations

A report suggests that Africa is on the verge of a fresh mining boom driven by demand in North America, India, and China that will only worsen existing ecological crises. Consumer demand for minerals such as tantalum, a key component for the production of electronics, lies at the heart of current mining operations.

Our understanding of colonialism is often limited to simple ideas about what we think colonialism looked like in the past. These ideas impede our ability to identify the complex ways that colonialism shaped and continues to shape the uneven power structures of the 21st century, as anthropologist and historian Ann Laura Stoler argues in her book, Duress.

Unequal power relations between and within developed and developing countries continue to define the causes and consequences of climate change. A clearer understanding of where these problems came from is a necessary first step towards solving them.

People in prosperous countries are often unaware that the garbage they throw out every day often gets shipped around the world to become somebody else’s problem.

While people debate whether climate change should be taken seriously from the comfort of their air-conditioned homes, hundreds of thousands of people are already suffering the consequences.![]()

Joseph McQuade, SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow, Centre for South Asian Studies, Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.