Don Pinnock, University of Cape Town

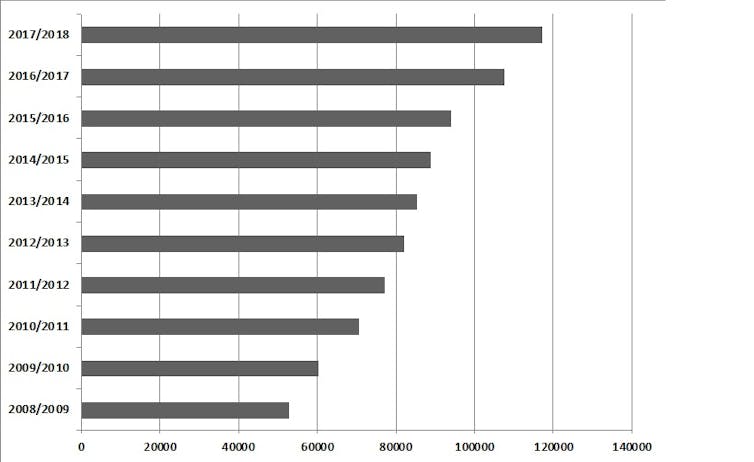

It’s not known exactly how many gangs there are in South Africa’s Western Cape province, but gang membership has been estimated at more than 100 000. Almost all these gangs, most concentrated in Cape Town, make the bulk of their money from procuring and selling illegal leisure drugs such as tik (crystal methamphetimine), heroin, nyaope (a street drug that mixes several illicit drugs) and dagga (marijuana).

Herein lies the conundrum: the criminalisation of possession and use of drugs creates conditions that are conducive for organised crime. This is why understanding the use, misuse and trade of illegal drugs is central to any intervention involving gangs and any policy relating to them.

This discussion is particularly important right now. Soldiers from the South African National Defence Force have moved into various suburbs in what’s known as the Cape Flats – an area of Cape Town racked by gang violence. But it will take more than armed soldiers to solve these seemingly intractable problems.

Criminalisation is a key issue to consider here. While all drugs are potentially harmful, there’s no doubt that criminalisation of possession and use creates enormous harms. Some of these relate directly to drug use. Others are about the production and supply of drugs. Perhaps the greatest harm is that young people are being caught up in the criminal justice system in huge numbers and ending up in jail where they are inducted into fierce prison gangs. Drug arrests are also wasting police time, clogging courts and filling prisons with young people.

It’s clear this present approach to criminalisation has failed. Cape Town – and South Africa’s – drug problem is escalating. At present the country is simply placing a potentially dangerous market into the hands of criminal syndicates and international traffickers.

A recalibration is urgently needed. In fact, the thinking around criminalisation is shifting globally. More than 50 years of prohibition, with more than a trillion dollars spent on enforcement worldwide in that period, have failed to prevent a dramatic rise in illicit drug use.

According to Transform, the UK organisation dealing with drug issues, “this is hardly surprising given that research consistently shows criminalisation does not deter use”.

How could South Africa do things differently?

Mapping drug routes

There are a few reasons that criminalisation simply doesn’t work.

First, illegal drug markets are characterised by violence between criminal organisations and the police; between rival criminal organisations; or both. The intensification of enforcement efforts simply fuels this violence.

Second, it is in the interests of criminal organisations seeking to protect and expand their business to invest in corrupting and weakening all levels of government, the police and the judiciary. These problems discourage investment in affected neighbourhoods. Meanwhile, limited budgets are directed into drug law enforcement, and away from health and development.

Another issue is that squeezing the supply of prohibited drugs in the context of high and growing demand inflates prices, providing a lucrative opportunity for criminal entrepreneurs.

A report by analyst and author Simone Haysom traces a heroin route that crosses Southern Africa from the East African “heroin coast” into South Africa’s cities and on to Europe and the Americas. This is one of three major heroin routes out of Afghanistan, which have their main markets in Europe and North America.

Until recently the southern route was considered to be the poor relation of the Balkan and central routes, which travel overland – and a much shorter distance – from Afghanistan to Europe. However, the southern route has become much more significant since 2000. This is principally because of an increase in opium production in Afghanistan; increased enforcement on the other routes; and persistent “impunity” for traffickers operating in East Africa.

In Cape Town, a significant proportion of street crime is related to the illegal drug trade. Rival gangs fight for control of the market and dependent users commit robbery to pay for drugs. The criminal justice-led approach has also caused a dramatic rise in the prison population of drug and drug-related offenders.

Alternatives

So what might an alternative approach to drug legislation in South Africa look like? International experience and research suggests the goal of any drug policy should be to:

Protect and improve public health;

Reduce drug related crime, corruption and violence;

Improve security and development;

Protect the young and vulnerable;

Protect human rights; and

Base policy on evidence of what works.

In terms of current discussions worldwide, this means retaking control from and disempowering organised crime syndicates which monopolise the drug trade. This requires markets to be legally regulated, availability controlled and drug over-use to be dealt with as a health problem. This would require an end to criminalisation of people who use drugs. A harm-reduction approach would also have to be adopted.

All aspects of such a market can be regulated –- from production through to use. It’s important to note that regulation does not constitute approval. Many of the drugs in question –- such as cannabis, amphetamines, cocaine, and various opiates, including heroin –- are already produced legally for medical uses without significant problems. Medical production models exist that indicate clearly how drug use can be carried out in a safe and controlled fashion.

A framework for regulation

What’s particularly useful about legal regulation, according to research, is that it allows controls to be put in place over everything from products (dose, preparation, price, and packaging) to vendors (licensing, vetting and training requirements); from who has access (age controls, licensed buyers, club membership schemes) to where and when drugs can be consumed.

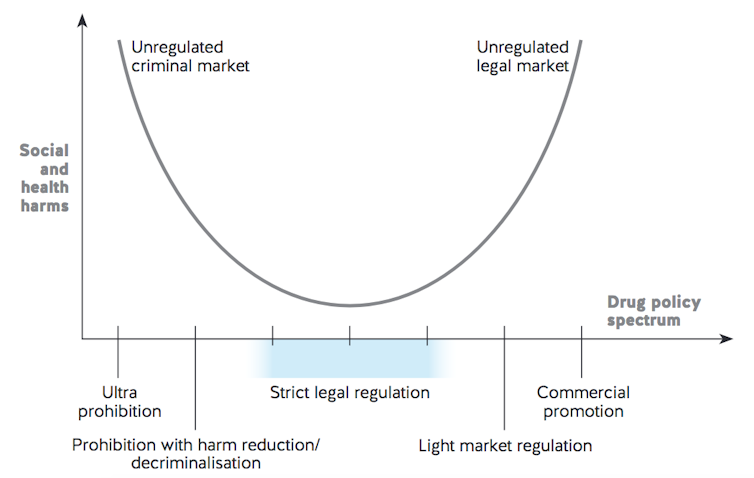

There is also a legal/policy framework spectrum within which the production, supply and use of leisure drugs can be understood.

Either end of this spectrum involves effectively unregulated markets – the criminal markets under prohibition at one end and legal, commercial free markets at the other. At both the prohibition and commercial ends, profit is the main driver; other outcomes are of little importance. In the middle lies an optimum level of government regulation – a point at which policy is both ethical and effective, because it represents where overall harms are minimised. This is true for all leisure drugs, including alcohol and tobacco.

Given the reality of continuing high demand for drugs and the resilience of illicit supply in meeting this demand, the regulated market models found in the central part of the spectrum are best able to deliver the most effective outcomes.

Drug market regulation is a pragmatic position that involves rolling out strict government control into a marketplace where currently there is none. And in Cape Town, it will have far greater positive ramifications than using the army to stop drug wars.![]()

Don Pinnock, Research fellow, criminologist, University of Cape Town

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.