Stephen Rocks, University of Oxford and Apostolos Tsiachristas, University of Oxford

In 2016 the then health secretary, Jeremy Hunt, declared child mental health services the “biggest single area of weakness” in the NHS. He might have added that it is also vastly underfunded. The mental health of children and young people accounts for less than 1% of all NHS spending.

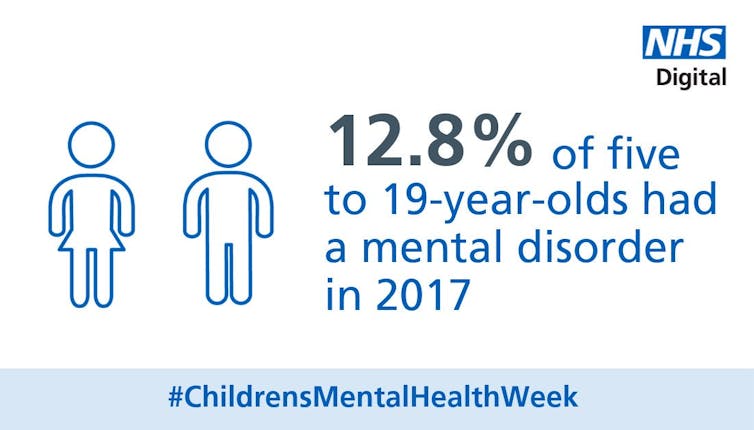

That is despite the significant burden that mental health problems impose on individuals, their families and society; despite one in eight young people having a mental health disorder; despite rising rates of self-harm and the fact that suicide is the leading cause of death among young men; and despite problems being serious enough to prompt the UK government to introduce a minister for suicide prevention in 2018.

Effective treatments exist, such as cognitive behavioural therapy and family therapy, and the sooner treatment is started, the more effective it is likely to be. Yet most young people don’t get help.

Read more: New ways to treat depression in teenagers

In England, two in three young people with a mental health problem do not receive support from specialist services. There are long waits for child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) and thresholds for entering care are high.

There is a clear disparity between the needs of young people and the resources dedicated to their mental health. Indeed, CAMHS accounts for around 7% of the NHS mental health budget even though children under 18 account for 21% of the population.

Why child mental health loses out

England has a decentralised system for providing healthcare, which means local areas commission most of their own health services, such as emergency services, hospital care, rehabilitation and mental health. NHS England assigns a budget based on how much it estimates an area needs, but it is up to local organisations called “clinical commissioning groups” to decide how to spend it.

Clinical commissioning groups spend widely different amounts on CAMHS, even after differences in population are accounted for. Our latest research shows that differences in spending can be explained not only by variation in the needs of young people but also by spending decisions in other areas.

Simply put, there are trade-offs. The NHS, like many health systems across the world, is under pressure. To increase spending on one area (CAMHS, for example) commissioners must decrease spending in another. That might result in someone waiting longer for surgery or to be seen at A&E. These are difficult decisions.

But CAMHS has been called the “Cinderella of the Cinderella” services, with many convinced that it is consistently overlooked. We think there are several reasons why child mental health may lose out to physical health when commissioners take spending decisions.

Rule of rescue. Spending decisions may be biased towards the “rule of rescue”, which predicts that spending will go towards immediate, life-threatening cases and away from prevention or early intervention – such as resolving a mental health disorder at a young age.

Lack of data. NHS targets have traditionally focused on things like A&E waiting times. With little data and, until recently, no targets for CAMHS nationally, commissioners have had less of an incentive to invest in these services.

Stigma. A lower level of awareness or stigma around mental health may have contributed to lower prioritisation of CAMHS in the past, and today’s decisions are constrained by the previous pattern of spending.

New technologies. Patients, doctors, private companies and even researchers may all have reasons to want new technologies to be adopted in healthcare. The lobbying for and adoption of new technologies may favour innovations, such as surgical instruments and drugs, over treatments that are labour intensive, such as talking therapy.

Read more: Key to lifelong good mental health – learn resilience in childhood

More, please

Things are improving. NHS England has started to collect new data, introduced a target to increase the number of young people receiving help and allocated extra funding to help local CAMHS transform (we are also trying to understand how much of a difference the transformation of local services makes). But a target of 35% of people in need receiving support is alarmingly low and many young people are still waiting too long for help.

Meanwhile, austerity in the UK is known to have hit children and lone parents particularly hard. Many services previously available to young people, such as children’s centres, have been cut following substantial reductions in local government budgets. This is expected to result in more young people needing support from specialist services.

The chance to intervene early is fleeting. Doing so requires a sea change in funding for young people both from within the NHS and other budgets.![]()

Stephen Rocks, Researcher, Health Economics, University of Oxford and Apostolos Tsiachristas, Senior Researcher, Health Economics, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.