Donald Trump is no Richard Nixon.

Nixon was a bully, a cynic and a crook who did all kinds of damage to American politics and society, not to mention to Cambodia and Vietnam, too. And yet he had a sense of obligation to his office — and to the Republican Party, a venerable institution that got its start in the 1850s by opposing the spread of slavery.

And so in August 1974, after the congressional leadership of the Republican Party told him that they wouldn’t stand for the Watergate cover-up, Nixon got on a helicopter and flew out of history.

This is not how the Trump era will end.

Moving right

The year 1977 marks a watershed in the modern history of the American right, a moment of departure from the kind of Republican Party that eventually rejected Nixon.

That year, the Cato Institution was formed in Washington to peddle free-market fundamentalism as the answer to America’s ills. Also that year, a group of fundamentalist Christians built Focus on the Family to uphold traditional patriarchy as God’s command. And a fringe group within the National Rifle Association turned what had been an apolitical hunters’ organization into a hyper-aggressive lobbying group for arms manufacturers and their most angry customers.

These groups shared a grand narrative of America, in which rugged individualists and virtuous families built the country with Bibles in one hand and guns in the other. The protagonists in this story were of course white, just like the great majority of the people in these movements.

From Reagan to Bush

During the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan drew these forces into an upbeat nationalism. America’s mission, he told the faithful, was to defeat godless Communism at home and abroad.

The subsequent collapse of the Soviet empire vindicated his take-no-prisoners approach — and the more extreme voices on the right, whose “think tanks” and pressure groups now formed a vast echo chamber impervious to political debate.

When Bill Clinton came to office in 1992, he hoped to appeal to centrist Republicans as a pro-business “New Democrat” from a southern state. Instead, a new wave of right-wing figures in Congress and beyond accused the Democrats of all kinds of perversions and impeached Clinton over his unseemly sex life, resulting in some bizarre political theatre.

Although these tactics narrowed the Republicans’ appeal, the party returned to the White House when George W. Bush squeaked out an electoral victory in early 2001. This kept the extremists within the party, for the moment.

Off the rails

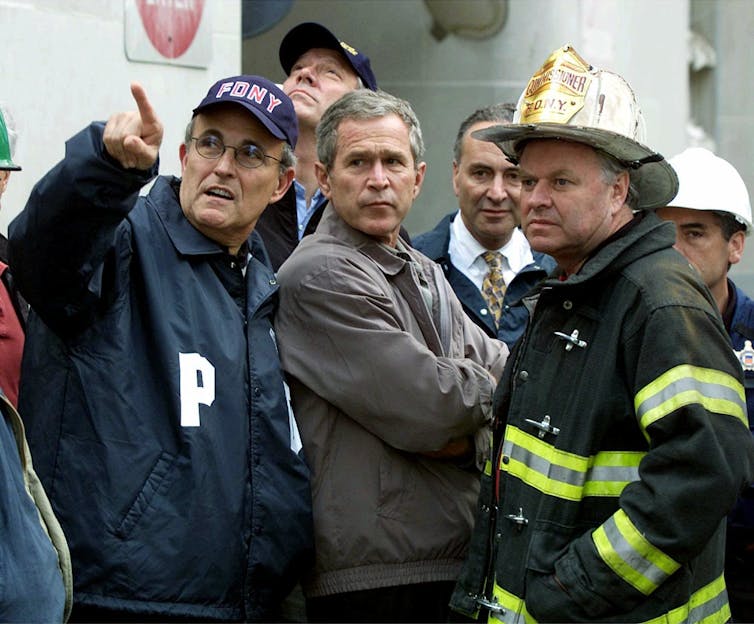

In the wake of terrorist attacks later that year, Bush briefly rose to Reaganesque stature with the economic and religious right, even though he scolded and disappointed white nationalists.

But while Reagan’s crusade against Communism had ended in global victory, Bush’s war in Iraq ground to a bloody stalemate. And as the recession of 2008 cast a dreary pall over America, Barack Obama rose to power by promising hope and change.

Although he, too, was a New Democrat in economic terms — his signature health-care law stemmed in part from another conservative think tank — Obama embodied the liberal vision of a multi-racial nation within a complicated world.

As president, he described his views on touchstone issues such as gay marriage as “evolving” and sought middle grounds with old enemies like Cuba and Iran.

In response, the far right took over the Republican Party, using not only think tanks and radio shows but also alt-right websites and chat rooms that became safe spaces for virulent racism.

Moderates were targeted

Extremists in the so-called Tea Party movement, which paved the way for today’s Make America Great Again supporters, targeted moderate Republicans while Fox News hosts and “shock jocks” called Obama a Marxist and terrorist sympathizer.

When Obama cruised to a second term against Mitt Romney, millions of Republicans turned to a helter-skelter politics of rage and paranoia — and into the arms of Trump, a vulgar demagogue of huge appetites and thin scruples.

Once again, this shrank the Republican Party’s field of voters to older, whiter and more conservative audiences. Against the uninspired campaign of Hillary Clinton, however, Trump stumbled into the White House with 46.1 per cent of the popular vote.

Toward November

Although most Americans don’t like him, Trump has an 80 per cent approval rating among Republicans. He uses this popularity, along with his Twitter feed, to bully Republican dissidents into silence.

In any case, the Republicans now have little choice but to double down on their far-right vision of America, using voter suppression to eke out more wins in the Electoral College. Having alienated almost every other demographic, they must stick with their Trump-loving base. They have no one else.

Indeed, the contemporary Republican Party has many elements of a cult of personality. Rick Perry, the former energy secretary, even recently likened Trump to the patriarchs of the Old Testament. The party does not even try to control its fringe elements; it is a fringe element, an anti-democratic force of recent history that threatens to consume the world’s oldest democracy.

This means that Trump will survive the impeachment process in early 2020, no matter what malfeasance comes to light. The Republicans will protect their man at all costs. And Trump will do everything he can to win in November, unburdened by any sense of propriety, fairness or facts. It’s not even clear if he would accept defeat.

Read more: Would Trump concede in 2020? A lesson from 1800

Against such a foe, the Democrats’ best chance is to lose their fear of it — and then call on their growing majority to demand a broader, more decent definition of government of, by, and for the people.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]![]()

J.M. Opal, Associate Professor of History and Chair, History and Classical Studies, McGill University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.