Carl James, York University, Canada

Recent reports of the schooling experiences of Black students in elementary, middle and high school in Toronto tell a story of negligence and disregard. This disregard includes a lack of access to appropriate reading materials and supportive relationships with teachers and administrators.

In conversations about their school life, Black students talk about adverse treatment by their teachers and peers, including regular use of the “n-word.”

These issues contribute to alienating and problematic school days for Black students. And none of this is new: racism in Toronto and Ontario schools has been ongoing for decades.

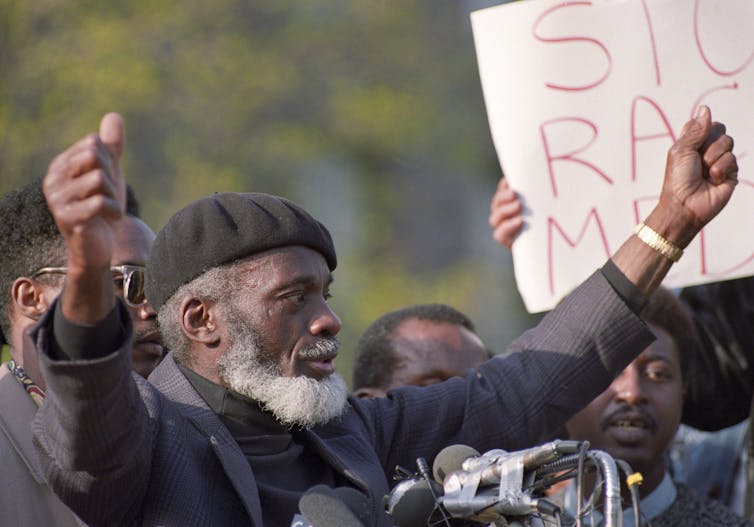

Twenty years ago, former politician Stephen Lewis was appointed to advise the province of Ontario on race relations. The appointment came after a “stop anti-Black police violence” march turned into an uprising in Toronto. Lewis spent a month consulting with people and community groups in Toronto, Ottawa, Windsor and London and then presented a report on race relations.

He wrote:

The students [I spoke with] were fiercely articulate and often deeply moving…. They don’t understand why the schools are so slow to reflect the broader society. One bright young man in a Metro east high school said that he had reached [the end of high school] without once having a book by a Black author [assigned to him]. And when other students, in the large meeting of which he was a part, started to name books they had been given to read, the titles were Black Like Me and To Kill and Mockingbird (both, incredibly enough, by white writers!). It’s absurd in a world which has a positive cornucopia of magnificent literature by Black authors. I further recall an animated young woman from a high school in Peel, who described her school as multiracial, and then added that she and her fellow students had white teachers, white counsellors, a white principal and were taught Black history by a white teacher who didn’t like them…

More than two decades later, reports continue to show that school boards do not meet the educational needs and interests of Black students and parents.

Two years ago, I led a study to examine the schooling experiences and educational outcomes of Black students. We surveyed 324 parents, educators, school administrators and trustees. We talked to Black high school and university students in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) who participated in the five community consultations we held in four school districts.

Participants echoed what students said 20 years ago in the Lewis report. Black students say they are “being treated differently than their non-Black peers in the classrooms and hallways of their schools.” They say there is still a lack of Black presence in schools. There are few Black teachers, the curriculum does not adequately address Black history and schools lack an equitable process to help students deal with anti-Black racism.

Read more: Racialized student achievement gaps are a red-alert

Students spoke about their teachers’ and administrators’ lack of attention to their concerns, interests and needs. They told of differential or “unfair” treatment, and they noted their teachers’ unwillingness to address complaints of racism.

Participants said they perceived a more punitive discipline of Black students. They also said they observed the “streaming of Black students into courses below their ability level.” They said Black students were discouraged from attending university.

Last year, I conducted another study with Black elementary, middle and high-school students in the Peel District School Board (PDSB), a multiracial district in Ontario. This study produced the same list of concerns.

Not belonging

Students reported being called the “n-word,” as they put it, by “people who are not Black.” This use of racial epithets adds to an already alienating educational climate for many Black students.

One middle school student said: “People are getting too comfortable with saying that n-word.”

A high school student shared his reaction to being called the n-word:

“I recall one time where I almost slapped this guy [for using the n-word]; but I was like: ‘Nah! I’m not going to let this happen or let him disturb me like that.”

Like Black students before them, their experiences contributed to their “sense of un-belonging” and a schooling environment that made learning problematic, tough and challenging.

Beyond Toronto, Black students and their parents are similarly complaining about the use of the n-word across Canadian public schools: Several news reports tell of parents in school boards in York, Ottawa, Montréal and Halifax.

One Montréal mother told CTV news that in an argument with his classmate, her son was called “the n-word” by a white student. The mother went on to say: “I’m at war with the systemic racism that occurs at the school.”

CBC Kids News published a story about two Black Grade 12 students in Nova Scotia who gave presentations to their peers across the province about being called the n-word. One of the presenters, Kelvin, said the word is commonly used to “hurt” and put him down.“ He said the word and its implications had not been taught by teachers in any of his classes.

Some parents and educators have connected this ongoing racism to a health and safety epidemic for Black students in Ontario schools.

That the "n-word” brings health and safety implications as well as deep consternation to Black students should be a concern that teachers take up. Teachers need to examine course materials for their content and impact on students’ learning.

Read more: Racism impacts your health

Could a good reading list help?

Based on my research, I recommended the Peel District School Board evaluate their curriculum and assess the usefulness of old texts. Some of these texts repeatedly use the the racial epithet, “ni–er.” As an example, I said the 1960 American novel To Kill A Mockingbird could be re-examined as a core book taught in classrooms.

These are texts that Canadian students might find difficult to relate to their lives. These texts become especially problematic when it is the only time that the lives of Black people are mentioned in class.

All teaching material must be continuously re-assessed in relation to historical, political and social contexts. Materials must also be evaluated for their ability to pertain to the realities of Black students in today’s classrooms.

The experiences of all students must be centred and the knowledge, needs and aspirations they bring into the classroom considered.

This is the same recommendation Stephen Lewis made in 1992.

Responsive learning spaces

As Poleen Grewal, associate director of the Peel District School Board pointed out, it is not just about the texts taught. Teachers who use uncritical texts as a way into discussions about racism are unlikely to benefit Black students already aware of racism. Grewal said teaching must be accompanied by the ability to create “culturally responsive learning spaces.”

Educators need to be aware of how structures of inequities like racism, classism, homophobia, xenophobia and Islamophobia operate in educational institutions to obfuscate student interest in learning.

Recently, a number of school Boards have initiated programs that they claim address anti-Black racism, including anti-racism workshops for teachers. Will these measures help to change the inequitable and racist contexts of Canadian schools and the racism students experience?

Other places have been pro-active with curriculum. In Nova Scotia, To Kill A Mockingbird was removed from the curriculum in 1996, and replaced with the 1998 novel A Lesson Before Dying by African-American writer Ernest J. Gaines.

School boards need to value and draw upon the cultural and intellectual capital of Black students. To do so, they need to encourage the university aspirations of Black students, address racism experienced by students, and use educational materials that enable a relevant and responsive learning environment.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter. ]![]()

Carl James, Professor, Jean Augustine Chair in Education, Community & Diaspora, York University, Canada

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.