Andrew Parkin, University of Toronto

A functioning democracy depends on the support of its citizens. The popularity of specific leaders and political parties may rise and fall, but ideally without affecting the extent to which citizens are satisfied with the political system and have trust in its core institutions, including the executive, the legislature and the judiciary.

In recent years, concerns have been raised about the decline in confidence in democracy in many Western countries.

Read more: Are we witnessing the death of liberal democracy?

In the Canadian context, these concerns appear overstated: on the whole, satisfaction with democracy and trust in the political system in Canada has gradually been rising over the past decade, not falling.

This national trend, however, may disguise divergent trends at the sub-national level. Given the country’s decentralized federal political structure, it’s essential to look deeper by focusing on provinces and regions.

Using data on Canadians from the AmericasBarometer surveys, the Environics Institute for Survey Research examined a variety of questions related to confidence in the political system.

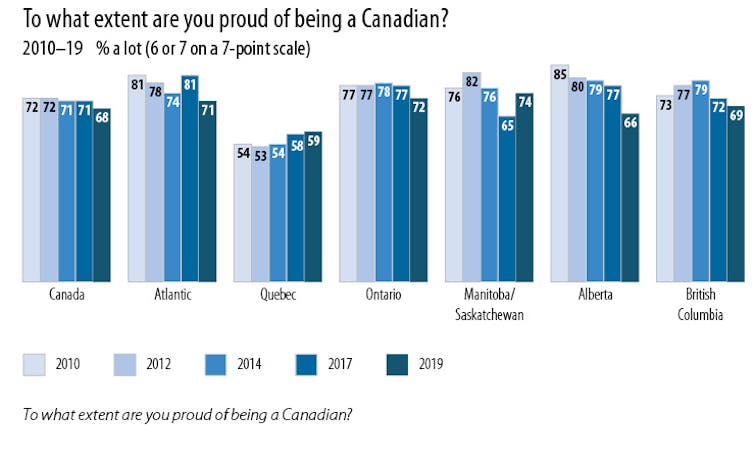

Polls of approximately 1,500 adult Canadians were conducted online five times over the past decade: in 2010, 2012, 2014, 2017 and 2019. These questions asked about satisfaction with, pride in, support for, respect for, trust in and approval of different political institutions or politicians.

In general, the survey results confirm that on these questions, national trends in Canada can be misleading, precisely because they often mask opposing regional ones. The answer to the question of whether Canadians are gaining or losing confidence in their democratic institutions depends in part on which region one is referring to. This can be illustrated in more detail by contrasting the trends in Québec and Alberta.

Québecers satisfied

Those concerned with national unity will find it reassuring that confidence in Canada’s political system in Québec is not significantly lower than average. This is notable given Québec’s status as a minority nation within the larger Canadian federal state — and one whose political leaders frequently contest the extent of the autonomy afforded to the province under the current federal arrangement.

Québecers are now slightly more likely than other Canadians to be satisfied with the way the political system works in Canada, and just as likely as other Canadians to be satisfied with the way democracy works. Québecers are also more likely than other Canadians to have a lot of respect for the country’s key political institutions, and just as likely to feel proud of living under the political system of Canada and to feel that that political system is worthy of support.

They have just as much trust as other Canadians do in elections, in Parliament and in the prime minister. They also have just as much trust in the Supreme Court, which is important since it is, among other things, the final arbiter of the federal-provincial division of powers.

Where Québecers stand out is on questions of identity. They are much less likely than other Canadians to feel a lot of pride in being Canadian (although very few feel no pride at all, indicating that while Québecers do not embrace a Canadian identity as strongly as other Canadians, most do not reject that identity either).

They are also much less likely to strongly agree that Canadians have many things that unite them as a country.

Trouble in Alberta

More worryingly, from a national unity perspective, is the finding that satisfaction with democracy and trust in the political system has declined significantly in Alberta.

Notably, the largest declines did not occur immediately after the start of the recession in the province in late 2014. The data suggest that Albertans initially remained hopeful, but that levels of satisfaction with Canadian democracy faltered after changes of government at both the provincial and federal levels in 2015 proved unable to quickly reverse the province’s economic fortunes.

To illustrate, in Alberta, between the 2017 and 2019 surveys:

• Satisfaction with the way democracy works in Canada fell by 19 points;

• Trust in elections fell by 10 points;

• Strong agreement with the proposition that “those who govern this country are interested in what people like you think” fell by 19 points;

• Strong respect for the political institutions of Canada fell by six points;

• Strong agreement that one should support the political system of Canada fell by 10 points;

• Strong pride in living under Canada’s political system fell by 10 points;

• Trust in parliament fell by eight points

• Trust in political parties fell by five points;

• Trust in the prime minister fell by 18 points; and

• Trust in the Supreme Court fell by 13 points.

In short, in Alberta, a decline was registered on a wide range of measures, and in each case, the decline was greater than that in any other region (in fact, in most cases, confidence in democracy in other regions improved over this period, with the exception of Atlantic Canada, which registered several modest declines).

Importantly, the declines are not limited to questions related to party politics (such as approval of the performance of the prime minister), but also to those related to support for the political system.

Slightly below average

These findings, drawn from a more comprehensive report entitled “Public Support for Canada’s Political System: Regional Trends,” show that these declines leave levels of confidence in Alberta only slightly lower than average.

This is because confidence in democracy was previously higher in Alberta than in the other regions. But even though Albertans don’t yet have significantly lower confidence in the country’s political system than other Canadians, they do stand out as the one region where confidence across a range of measures has declined sharply in recent years.

The main takeaway from this analysis is this: if the trend continues, a significant gap in support for the political system will emerge between Alberta and the rest of Canada.

Andrew Parkin, Executive Director, Environics Instittute / Sessional Lecturer, Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.