UOn January 3, 2020, the decades-long conflict between the United States and Iran almost turned into a full-scale confrontation when a US drone assassinated Iranian major general Qasem Suleimani as well as Commander Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis.

Iran and its allies vowed revenge and global markets, fearing a military escalation, anxiously awaited their reprisals. On January 8, however, Iran’s military chose to target two American military bases located in Iraq with missiles that caused material damage rather than human losses. With the United States’ answer limited to imposing new sanctions rather that resorting to the military option, the situation cooled down despite the continued exchange of fiery words.

In this article, we analyse the impact of this conflict on energy markets, especially should a military confrontation result in the closing of Hormuz strait. Who would be the economic winners and losers? What are Iran’s pressure options?

The immediate effects of January’s skirmishes

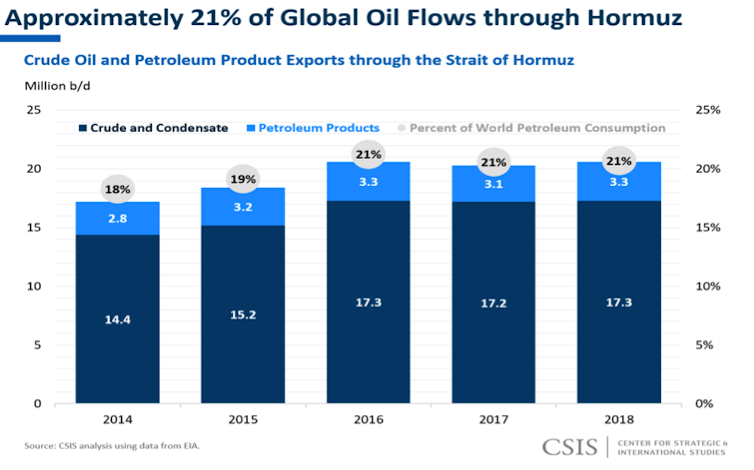

Up to 21% of the world’s oil flows through the Strait of Hormuz, making it a strategic chokepoint – over the course of 2018, an average of 20.7 million barrels of oil passed through it per day. The strait is also crucial for liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports, as more than 25% of the world’s supply, mostly from Qatar, passes through it annually.

The short-term effect of January 3 strike was a rise in the price of oil, which was expected. Brent crude hit US$70.73 per barrel, its highest level since September 14, 2019, when it was US$72.

Goldman Sachs and UBS analysts doubt whether oil prices will keep rallying beyond US$70 because of strong production from outside the Middle East – primarily the United States and Norway – which would prevent prices from surpassing US$70.

Following Iran’s strikes and US decision not to hit back, tensions eased, which resulted in a further drop in oil prices and by January 10, when fell to around US$65.

Possible winners and losers

According to Capital Economics, a war would lead to oil prices more than doubling.

“While the price of Brent could soar to as much as $150 per barrel, the rally may prove short-lived as supply networks adjust and demand falters in the wake of higher prices.”

Defining the winners and losers from this conflict is directly based on their status as oil importers or exporters.

Persian Gulf: Iran, Kuwait, Qatar and Bahrain oil exports pass entirely through Strait of Hormuz, and Qatar also uses it to export LNG. Were the strait closed, they would be hit hard. As for Iraq, 90% of its oil transits through it. The UAE can send part of its production (1.5 million b/d) via a pipeline to the port of Fujairah on the Gulf of Oman. Saudi Arabia has the greatest ability to divert flows, by using a mega-pipeline to an export terminal on the Red Sea. Saudi Aramco said the capacity of that line would be increased to 6.2 million barrels per day by the end of 2019.

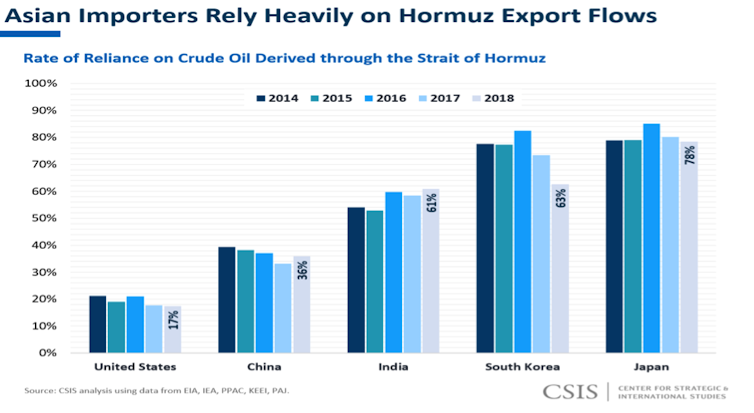

Asia: China, India, Japan and South Korea rely heavily on Middle Eastern oil, as shown in the graph below and their economic performance would suffer in the short term.

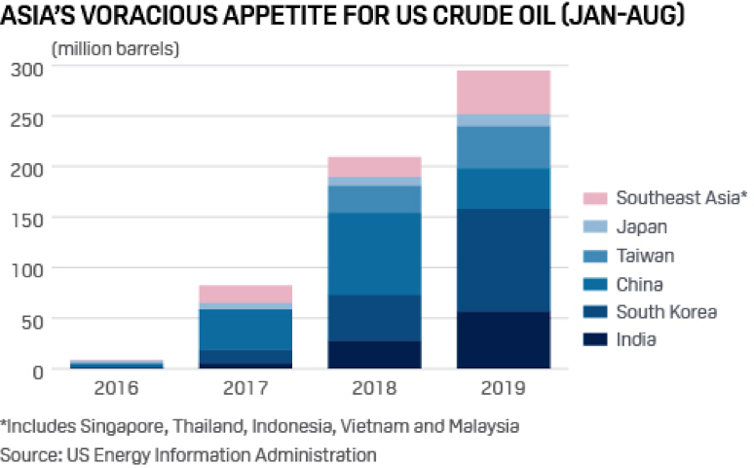

However, since the United States re-imposed sanctions on Iran, and the waivers the US administration provided to certain countries to continue importing Iranian oil ended in May 2019, Asian nations have been pivoting to US imports. The graph below shows a spectacular increase.

European Union: Oil accounts for 35% of the EU’s energy mix. It imports only 20% of its oil needs from the Middle East and therefore its dependence on this source is limited. However, Qatar is Europe’s largest LNG exporter (35%), and any disruption of supplies could leave important consequences for the EU.

United States: According to MoneyWeek Review:

“The fracking revolution means that finding hydrocarbons and getting them out of the ground has never been easier, particularly in North America. When prices jump the frackers are happy to start pumping.”

This being the case, the United States would be an obvious winner of such a crisis.

Russia: The country’s commitment to the OPEC+ deal has allowed it to gain huge amounts of additional revenue. However, that deal resulted in Russia having a spare production capacity of up to half a million barrels per day. Should prices jump, Russia could be tempted to use such an opportunity to fill in its coffers and boost its GDP performance to match President Putin’s desired GDP growth rates.

Iran’s options

Tehran’s economic woes can still make its behaviour unpredictable especially if the harsh sanctions continue. So far, it seems to have used a fraction of the means at its disposal. A measured military response saved face and halted a potential escalation had they incurred human losses on the US military.

Iran still has the following ways that it can strengthen its position, among others:

Encouraging its allies to attack US interests, allowing Iran to avoid the blame. Attacks could spread to US allies such as Israel.

Cyber-attacks against US and allied companies and administrations.

Attacks on or seizure of oil tankers (such as in 2019) or the use of drones against neighbours’ energy facilities.

Iran’s fleet can pursue commercial shipments in the Gulf of Oman, Indian Ocean and elsewhere.

The country’s Houthi allies can target ships in the Red Sea, thus threatening the Suez Canal’s economic viability.

Despite significant loses since the waivers were terminated, Iran chose to not close the Hormuz strait. Why? Because Tehran noticed that relying on “precise, quick and short” actions, especially through allies, proved more profitable. It does not have the capacity for a full-scale war with the United States and finally it does not wish to be seen as an unreliable partner in the post-sanction times.

With the US presidential elections approaching, Iran’s internal troubles mean that both countries need the current “ceasefire”. Perhaps following the short-lived skirmishes, both sides could go back to the negotiation tables and find the necessary compromises to reinstate the nuclear deal. Only time will tell.

This article was written with Ahmad Ismail, an Abu Dhabi–based research consultant specialising in political-economy analysis and geopolitics.![]()

Hassan Obeid, Professor of Finance, European Business School, INSEEC U.

Cet article est republié à partir de The Conversation sous licence Creative Commons. Lire l’article original.