David Hunter, University of Oxford

The fight against COVID-19 has launched a thousand military metaphors in the British press. The “greatest challenge since the Second World War”, “the frontline”, the virus is an “invisible enemy”, and so forth. Us citizens feel besieged and under threat as we retreat to our foxholes.

If this is a war, how is Britain doing? The frontline troops are running out of protective gear (PPE), ammunition (beds) and heavy equipment (ventilators). Supply lines are stretched thin. Meanwhile, the country’s leadership – the prime minister, secretary of state for health and the chief medical officer – are self-isolated in their bunkers where they cannot be functioning at 100%.

The enemy moves among us unseen. In the fog of war, we are relying on case counts to track its movements – as if the Royal Observer Corps are spotting planes and calling in their locations. We should have radar to look over the horizon (routine testing for the virus) to tell us where it is massing and will strike next.

The phoney war is over – the Battle for Britain is well under way.

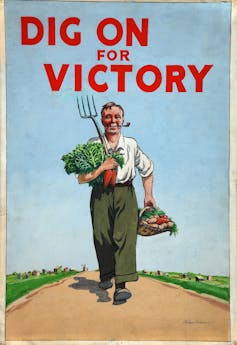

What do we need? We need the PPE and ventilators to reach the troops at the right time. But we also need reliable intelligence on the enemy’s movements – we need to be able to test for the virus, and to test for past infection and current presumed immunity. We need these tests at the front line to work out who should be, and who should not be, in the trenches. We need the tests for the civilian army – to decide who can safely supply the elderly and infirm, staff the nursing and care homes, who can “dig on for victory” by maintaining the chain of food and essentials, and who should continue to isolate at home.

The technologies exist, but confusion reigns: “3.5 million tests for virus exposure will be available within days”. Well, no, “But health officials said … that it could be several weeks before testing can begin”. “Ten thousand tests today”? We did less than 8,000.

A single PCR machine can test 350 people in a matter of hours. Even with only two shifts a day, 20 such machines could provide 14,000 tests a day. Many of the big labs in the UK have a battery of 20 or more machines. What has gone so badly wrong?

No answer

The same thing that has so often gone wrong after a surprise attack. Blurred lines of command, inadequate equipment stockpiles, unclear jurisdictions, supply lines cut off. Public health professionals are asking what the plan is to expand testing, and who is in charge and accountable to ramp it up? There seems to be no answer.

Since we are engaged in military metaphors, why not go all the way? What do we need in this time of crisis? We need someone in charge whose expertise is commissioning, or commandeering supplies, and delivering those supplies under fire.

It could be a real general – with actual experience in provisioning the frontline troops. It could be a captain of industry – maybe someone who has spent years ensuring that deliveries reach tens of thousands of shops every day, or that chemists do not run out of stock. Ideally, it would be both.

We are told the reagents cannot be imported because other countries are keeping them, but the reagents are relatively simple to manufacture – South Korea asked its biotech companies to make them in late January and had tests made and approved in three weeks.

Appoint a commander

If we are in a war, appoint a commander and give them powers to requisition equipment and laboratory space and to second personnel. Get the tests up, running and available. Make a battle plan on who should be tested first (the frontline troops and their patients, then nursing home workers and carers), and then how to implement national surveys so we know where the virus is and will appear next.

Many public health professionals are urging that we do not stop there. The way out of a locked-down economy may be frequent testing of everyone in the country who is not antibody positive, so we can turn a second attack wave into a series of skirmishes.

A prominent epidemiologist has invoked the “Dunkirk spirit” to recruit “every lab in Britain with a PCR machine to do COVID-19 testing”. We should be guided by scientists, but be aware that scientists have little expertise in supply chain management. We need the boffins to design the weapons, but we need logistics officers to manufacture and deliver them, and an information system to return the results.

One thing has no place in this war – censorship. We need a daily report not just on the casualties, but on the progress in implementing the plans and delivering the goods. We don’t need propaganda about armies that don’t exist or bringing the troops home by Easter – as US president Donald Trump suggested recently. If truth is the first casualty of war, we need to fight this one by new rules. Report the facts, keep the generals honest. Careless talk costs lives. These are testing times – we need to test!

David Hunter, Richard Doll Professor of Epidemiology and Medicine, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.