India introduced a national lockdown on March 24 hoping to curb the spread of the coronavirus pandemic. As April 2020 begins, the country has registered over 1,500 cases of COVID-19, the disease associated with the new coronavirus, according to the latest data available.

These numbers translate into surprisingly low prevalence rates compared to the rest of the world due to the delayed arrival of the virus. But it is possible the scenario could get much worse, while experts are warning that India is at grave risk notably due of the vulnerability of its health system.

Personal hygiene and more specifically handwashing practices have come under scrutiny as millions of India’s poorest do not have access to basic amenities. We are social demographers and have specifically investigated the data about handwashing practices in India for this article.

In India, research has shown how good hand hygiene reduces the risk of diarrhoea, pneumonia, or stunting – prime factors of high infant and child mortality.

Read more: Coronavirus: what might more hand washing mean in countries with water shortages?

Unfortunately the focus on handwashing was not included in the large Swachh Bharat Mission, or Clean India programme, launched in 2014. The spread of the coronavirus has brought back this issue to the fore as hand hygiene is one of the easiest ways to avoid both catching and spreading the virus.

Hand hygiene in India

There is a debate about the reliability of surveys on handwashing and how statistics are captured. According to a national survey in 2011-12, 63% of households reported usually washing their hands with soap after defecation, a low figure for a country where toilet paper is rarely used.

More recent research conducted in India has, however, shown that the most reliable statistics about hygiene practices are derived from an environmental check in which fieldworkers inspect the house for the presence of a water source with soap where people wash their hands.

This is how information was collated in India’s last national demographic survey coordinated by the International Institute for Population Sciences in 2015-16, from where the data for this study was drawn. It found that 39.8% of households had no soap or no water, a situation often explained by the absence of soap during the survey.

Huge geographical variations

India’s proportion of households without soap or water is lower than the 71.4% of people in Bangladesh or 52.9% in Nepal lacking such amenities. But Indian households fared worse than Pakistan (31.4%) or Myanmar (16.4%) during the same period.

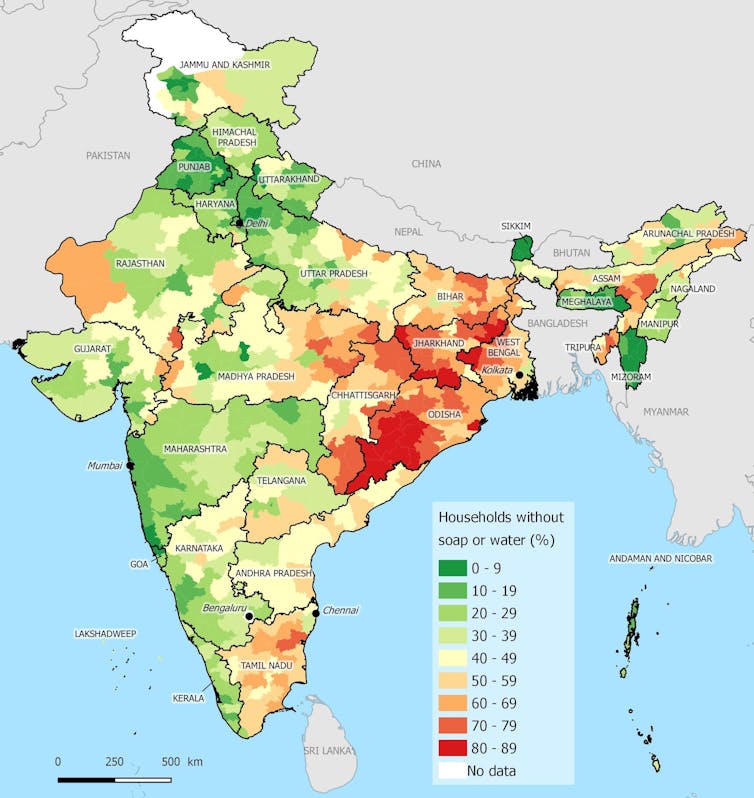

When the data is broken down, we found that 20% of households in urban areas, where access to running water is more common, had no handwashing facilities, compared to 51% in rural areas. Regional disparities are even wider: ranging from below 10% in Delhi to above 60% in the entire state of Odisha. As the map below shows, the best hand hygiene can be found in Northwest India, in coastal Western India, as well as in many states of the Northeast. In contrast, districts where handwashing facilities are the least common are clustered around Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and Jharkhand.

The map also highlights another pocket of poor hand hygiene in the more developed Tamil Nadu state in southern India. In fact, while spatial patterns of hygiene are very pronounced, the map of lower use of soap and water does not exactly correspond to the least developed regions of India.

Socioeconomic inequalities

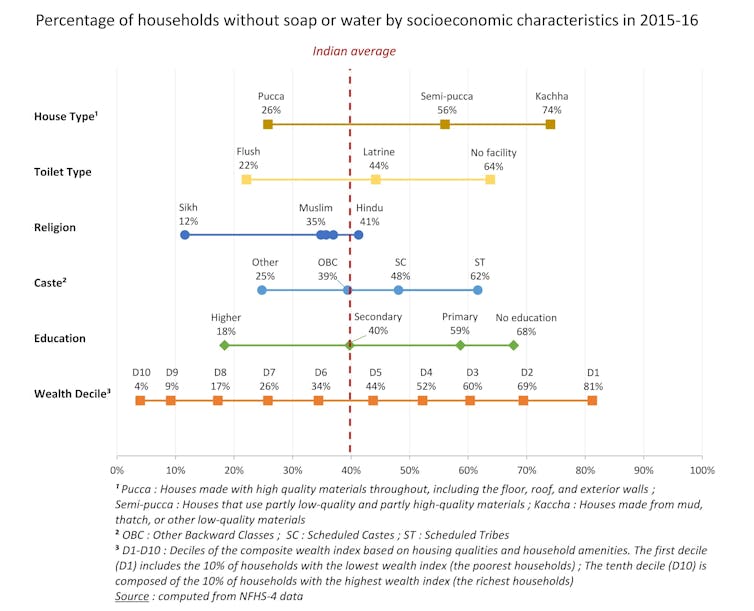

Our research also looked at social and economic characteristics of households. We found that only 4% of the richest households didn’t have handwashing facilities, compared to 80% of the poorest households. The worst levels of hand hygiene were observed in houses with an absence of toilet facilities (64%) or in illiterate families (68%).

The implications of these inequalities may be considerable for the transmission of the disease within the country and the impact on vulnerable groups.

Labourers, maids, cooks, drivers, daily wagers, people working in small businesses in towns and cities are now losing their livelihoods. With no economic plans to support them, they are going back home generating the largest sudden migration India has seen since Partition in 1947.

Very soon they may carry COVID-19 back to their neighbourhoods and native villages and transmit the virus further across the country. The situation is particularly worrying in households composed only of old people above 65 years, with less than half of them having access to soap and water.

The benefits of handwashing in India extend well beyond the coronavirus since it reduces the spread of pathogens of all types. In 2017, researchers estimated the annual net costs to India from not handwashing were US$23 billion, stressing the considerable gains relating to decreases in diarrhoea and acute respiratory infection for India from behavioural changes. Local initiatives have already emerged to encourage the population to wash hands frequently.

Experts also point out that although handwashing should be more widespread, lack of access to water – particularly clean water – in India may be another challenge for the poorest communities to protect themselves from coronavirus.

In this context, handwashing campaigns during the crisis will be crucial for public health in India – alongside an increase in access to basic amenities for all.![]()

Christophe Z Guilmoto, Senior fellow in demography, Institut de recherche pour le développement (IRD) and Thomas Licart, Doctorant, démographie, Université de Strasbourg

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.