Tania Das Gupta, York University, Canada

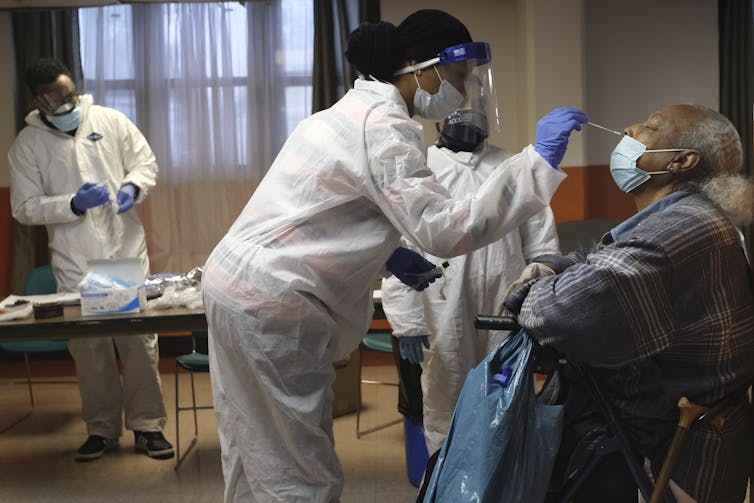

COVID-19 has most severely affected elderly residents and their caregivers in long-term care nursing homes. In Ontario, coronavirus has claimed the lives of well over 1,400 people, both residents and caregivers, in the long-term care system. Although many issues have been discussed in relation to this crisis in long-term care, one crucial factor has not been discussed as much: the issue of race.

Why is race important here? Nursing homes and long-term care in Canada are predominantly staffed by immigrant women, migrants and refugees — mostly women of colour. In Montréal, up to 80 per cent of the workers in long-term care are racialized women.

Many of us have recently learned that long-term care homes are increasingly funded by the private sector animated by profit-making. This business model has created challenging conditions within which COVID-19 and other infections rapidly spread.

A team of researchers led by Pat Armstrong at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) said the high incidence of deaths in long-term care homes are an indication of the lack of value placed on two groups of people: the elderly and their caregivers.

Having a conversation on racism is a challenge in an environment where race talk is often seen as an indication of racism. Even the collection of race-based data has been controversial.

The reluctance to speak about race in long-term care homes may be contributing to what appears to be race-blind reporting of the way the pandemic is impacting communities.

Essential workers earning low pay

In general, long-term care workers are so poorly paid that many have to survive by combining multiple jobs in different care homes. As a result, they can inadvertently become potential carriers of infection. But they often have little choice.

Many are not unionized, which means they do not have sick leave benefits. Even if they are not feeling well, some would hesitate to stay home because of lost income.

British Columbia recognized this issue and acted quickly. The province restricted caregivers to one nursing home, topped up their wages and made them full-time workers. If we were not in the middle of a pandemic affecting elderly residents would these reforms have been made? Probably not.

To make profits in these privately owned and operated care centres, owners have relied on a racialized and gendered workforce of immigrant and migrant women, assumed to be both cheap and disposable. Their cheapness and disposability are predicated on societal assumptions about their inferior quality of labour, lack of skills and unavailability of better employment opportunities.

Despite the fact that they are considered “essential” workers, they earn low wages, are insecure and even subjected to workplace violence. Expendability becomes synonymous with long-term care workers.

Research conducted by the Canadian Union of Public Employees and Ontario Council of Hospital unions concluded that about 90 per cent of long-term care staff in Ontario have suffered physical violence, while around 70 per cent of racialized and Indigenous staff have experienced related harassment. This culture of violence is due to their social vulnerability as women of colour and as immigrants.

Lack of personal protective equipment

The perceived disposability of these workers is perpetuated not only by their insecure status as part-time, temporary and contractual workers, but also due to their status as newcomers and non-citizens.

Most importantly, society has marked their disposability on their brown and Black bodies.

It seems that “this government chose who lives and dies” as Sharleen Stewart, president of the Service Employees International Union, aptly commented at the funeral of a personal support worker. Stewart was referring to the lack of PPE for workers in long-term care and nursing homes.

Recently, the Ontario Nurses’ Association went to court seeking orders against a number of long-term care homes that had restricted or not provided protective equipment for its members and residents. Many failed to provide N95 respirators to workers looking after residents. These were homes where a significant number of deaths had already taken place from COVID-19.

The association alleged that in some cases workers had been ordered not to wear masks lest it frighten the residents. Nurses and caregivers were in close contact with coughs, sneezes and spit up food from elderly patients with trouble swallowing. The Ontario Superior Court ruled in the association’s favour.

Ensuring human rights

Despite their essential service, nursing home workers and personal support workers are often portrayed as being unskilled, untrained and even neglectful in their conduct. Indeed, they have sometimes been portrayed as being responsible for the spread of COVID-19 in nursing homes.

Recently, the Ontario government announced a plan to establish an independent commission into Ontario’s long-term care system. As we contemplate the terms of reference of such a commission, the issue of race in long-term care work is important to address.

As Armstrong and her team at CCPA succinctly said, the “conditions of work are the conditions of care.” COVID-19 related deaths in long-term care homes have made visible not only the neglect of the elderly in our society but also the neglect of support workers — many of whom are migrant and immigrant women — providing essential work in these centres.

Both are vulnerable to infections, illness and death. The question of race in long-term care is not only important for ensuring the best care for seniors but also to ensure their human rights and those of their caregivers. This requires that we acknowledge and open up a conversation about race on the job.![]()

Tania Das Gupta, Professor, Department of Equity Studies, York University, Canada

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.