Russell Cobb, University of Alberta

For only the second time in a century, the world’s attention is focused on Tulsa, Okla. You would be forgiven for thinking Tulsa is a sleepy town “where the wind comes sweepin’ down the plain,” in the words of the musical Oklahoma!.

But Tulsa was the site of one of the worst episodes of racial violence in American history, and a long, arduous process of reconciliation over the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 was jarred by President Donald Trump’s decision to hold his first campaign rally there since the COVID-19 pandemic began.

The city is on edge. Emotions are raw. There’s anxiety about a spike in coronavirus cases, but lurking even deeper in the collective psyche is a fear that history could repeat itself. Tens of thousands of Trump supporters will gather close to a neighbourhood still reckoning with a white invasion that claimed hundreds of Black lives.

A Trump rally near a site of a race massacre during a global pandemic already sounded like a recipe for a dangerous social experiment. But then there was the matter of timing. The rally was to be held on Juneteenth (June 19), a holiday commemorating the day slaves in the western portion of the Confederacy finally gained their freedom.

Normally, Juneteenth in Tulsa is one big party, the rare event that brings white and Black Oklahomans together. But fears about spreading COVID-19 led organizers to cancel the event. Then came the protests over the murder of George Floyd. During those demonstrations in Tulsa, a truck ran through a blockade of traffic, causing one demonstrator to fall from a bridge. He is paralyzed from the waist down.

COVID-19 cases surging

To make a bad situation even worse, the city is witnessing a surge in coronavirus cases. Local health officials have acknowledged that the increase in new cases, mixed with close to 20,000 people packed into an arena, is “a perfect storm” that could fuel a super-spreader event.

Some of Mayor G.T. Bynum’s biggest supporters began pleading with him to cancel the event. Bynum is of that rarest of species, a Republican who has staked part of his political legacy on combating racism. It was Bynum who shocked the white establishment by ordering an investigation into potential mass grave sites from the 1921 massacre, even as many Republicans accused him of opening old wounds.

Faced with the prospect of provoking a fight with Trump, however, Bynum equivocated.

Bynum found himself under attack from former friends and allies who urged him to do something. Then, on June 13, the Trump campaign announced that it would change the date of the rally to June 20 “out of respect” for Juneteenth. It was a small victory for protesters, but some were further enraged by Bynum’s moral equivalence between the protests over Floyd’s murder and a Trump campaign rally.

Reminiscent of another mayor

The mayor’s impotence has also brought back memories of 1921. The mayor then, T.D. Evans, found himself unable — or unwilling — to stand between an angry white mob ginned up over fears of a “Black uprising” and a Black community demanding racial equality.

Evans saw the rising influence of the Ku Klux Klan in Oklahoma politics and quietly voiced his displeasure. As the Tulsa Tribune cultivated white paranoia about a Black invasion of white Tulsa, Evans, and many like him, did little. “Despite warnings from Blacks and whites that trouble was brewing,” Tulsa Word reporter Randy Krehbiel wrote in a book about the massacre, “(Evans) remained mostly silent.”

One historical parallel with 1921 stands out above the rest: the power and influence of “fake news” to mobilize alienated voters.

While much has been made of a revolution of social media and YouTube to undercut the gatekeepers of traditional media, a false news article was the most proximate cause of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921.

The Tulsa Tribune published an article on May 30, 1921, with an unproven allegation that a Black man, Dick Rowland, had tried to rape a white woman in a downtown elevator. The dog-whistle came through loud and clear. No evidence was presented and charges were later dropped. But the news was enough to set off calls for a lynching of Rowland.

Hundreds killed

A mob formed around the Tulsa courthouse. The Tribune had been stoking fears of a “Black uprising” for months, running stories of race mixing, jazz and interracial dancing at Black road houses.

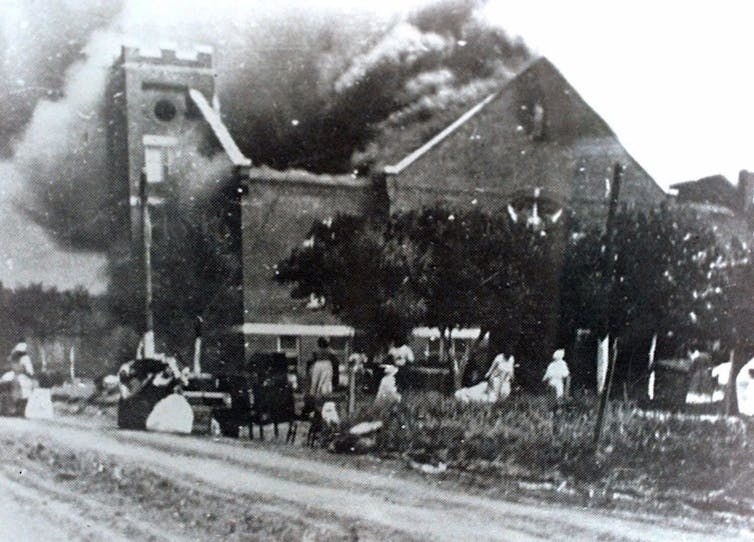

A few Blacks armed themselves and tried to stop the lynching. The sight of armed Blacks made the white mob direct its fury at a bigger target — the Black section of town, Greenwood.

By the dawn of June 1, 1921, Greenwood lay in ruins, with hundreds dead and thousands interned in camps. The devastation did not come as a surprise to those who had watched the rise of xenophobia during the First World War and the second coming of the KKK, an organization that received a boost after the screening of the racist film The Birth of a Nation in 1915 at the White House.

Tulsa, and the nation, had been primed for racial violence by a white supremacist media and presidential administration. Many well-intentioned people stood idly by, hoping the trouble would soon blow over. It did not.

Karl Marx wrote that history repeats itself, the first time as tragedy, the second as farce. During the spring of 1921, Tulsa got the tragedy. With Trump rallying tens of thousands of his supporters near Greenwood amid a deadly pandemic, the best we can hope for this time around is farce.

Russell Cobb, Associate Professor of Latin American Studies, University of Alberta

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.