Johannes Petry, University of Warwick

Relations between London and Brussels have been better. While Brexit dominates the headlines, another cross-channel development has recently captured the attention of financial institutions. It concerns the the London Stock Exchange’s proposed US$27 billion (£21 billion) acquisition of US financial company Refinitiv, into which the European Commission is carrying out an in-depth anti-trust investigation.

With a ruling due in October, the commission is likely to reject the deal in its current form. To win approval, the LSE recently declared it was selling either the whole of Borsa Italiana or its bond-trading platform, MTS.

Why does the EU care about the LSE’s acquisition of a US financial data company? And why would the LSE sell the Italian stock exchange to quell these concerns? The answer lies in the fact that stock exchanges have transformed fundamentally over the last 25 years, as I demonstrated in a recent paper. This has largely gone unnoticed and public perception clings to an outdated understanding of what exchanges are.

How exchanges changed

Stock exchanges are often still viewed as quasi-public marketplaces – icons embedded within nation states and crucial for national economic development. But they have in fact become powerful global corporations which actively shape the development of capital markets around the world – with important implications for investors, companies and states.

As an article in The Banker put it a few years ago: “Until the 1980s, exchanges would … have been recognisable to a merchant who was trading in the 14th century – the time of their inception.”

Exchanges used to be non-profit organisations, controlled by their members, with little agency of their own. They usually monopolised trading in their area, and were physical trading locations, such as the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, pictured below.

This has changed in various ways. Financial liberalisation reforms such as the EU Investment Services Directive (1993) created competition between exchanges. No longer monopolies but a marketplace for marketplaces, they were forced to modernise and become more efficient and customer-focused.

Most demutualised and converted into listed companies. As one exchange official noted, they were now independent actors “fully in charge of their own destiny”. At the same time, they also became profit-driven companies.

The shift towards globalisation also meant more cross-border financial integration. Alongside the growing competitive pressures, there were opportunities to scale up, acquire competitors and venture into new markets. From Chicago to Singapore, futures exchanges started buying stock exchanges and vice versa, plus trading venues for bonds, carbon emissions and commodities. Former NYSE CEO John Thain had once observed that “every country has an army, a flag and an exchange”, but now exchanges were forming huge organisations spanning the globe.

Finally, exchanges turned from physical trading locations into financial technology companies. Face-to-face interaction on trading floors was gradually superseded by electronic markets. The manager of one exchange noted in an interview: “We are of course known as a US exchange but that’s only about 10% of our revenue.” Digitisation had fundamentally changed the game as market technology, data and indices increasingly drove exchanges’ profit.

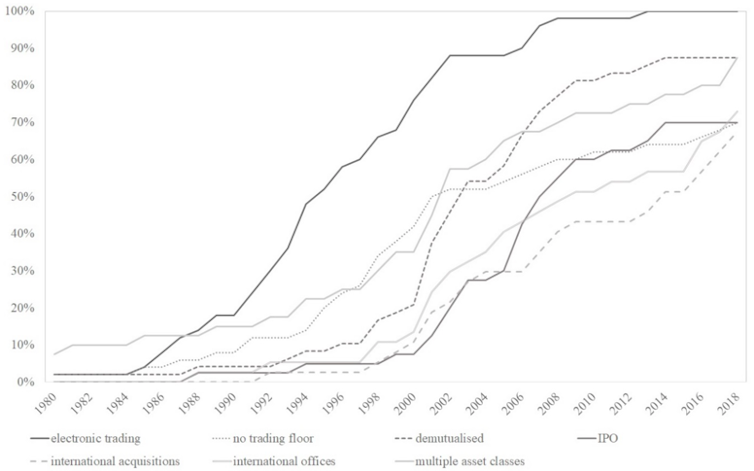

The transformation of exchanges, 1980-2018

Exchanges are now actively creating, regulating and shaping markets around the world. They control the very infrastructure of global finance - data, indices, financial products, trading platforms and clearing, essentially deciding how markets work for companies, investors and states.

Why LSE-Refinitiv matters

A hierarchy has also emerged, with LSE one of a handful of global players that now dominate capital markets, along with CME, ICE, Cboe, Nasdaq and Deutsche Börse. These groups run the largest, most prestigious and profitable markets, and own the most important products, indices and technological know-how. While there are over 100 exchanges worldwide, these six companies account for over 50% of industry profits, and trading in stocks, futures and options.

LSE is now a central node in global and, importantly, European capital markets. It owns FTSE Russell, one of the leading index providers that steer investments by deciding which companies and countries are included in the indices tracked by global investors - essentially acting as a gatekeeper for global finance.

LSE owns LCH Clearnet, the world’s largest clearing house. Clearing houses act as middle men (or

countries’ refinancing operations as some government bonds were no longer deemed safe.LSE also owns several European trading platforms for stocks, bonds, derivatives and exchange-traded funds – including Borsa Italiana and with it the MTS platform. As Bloomberg recently noted, MTS is a critical piece of European bond-market infrastructure with average daily trading volumes exceeding €100 billion (£90 billion). It is a key venue for trading Italian and other European countries’ government debt. Refinitiv (previously the financial unit of Thomson Reuters) owns Tradeweb, an even larger bond-trading platform.

Together with the MTS bond trading platform, FTSE Russell’s bond indices and LCH collateral rules, LSE’s acquisition of Refinitiv would have created a quasi-monopoly in the European government-bonds trading infrastructure. With European sovereign debt already highly politicised in recent negotiations on the EU’s coronavirus recovery fund, an institution with the power to shape this market that will probably be outside of the EU’s regulatory reach come December is hardly acceptable for EU regulators. The EU already blocked a proposed merger between LSE and Deutsche Börse in 2017 for similar reasons.

With the threat of LSE’s market dominance averted, the EU might allow the LSE-Refinitiv deal to go through after all. But what this episode demonstrates is that as crucial building blocks of global finance, exchanges have become important counterparts to states. What they own and what decisions they make have become matters of international political importance – and has added an extra layer of complexity for governments trying to set the rules for global finance.![]()

Johannes Petry, ESRC Doctoral Research Fellow in International Political Economy, University of Warwick

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.