Before becoming known as the goddaughter of Queen Victoria, Sarah Forbes Bonetta had a royal life of her own. She was the daughter of an African chief before being captured and presented to the Queen of England as a gift in 1850. Her story is presently being told by English Heritage, a charity that manages over 400 historical sites in England.

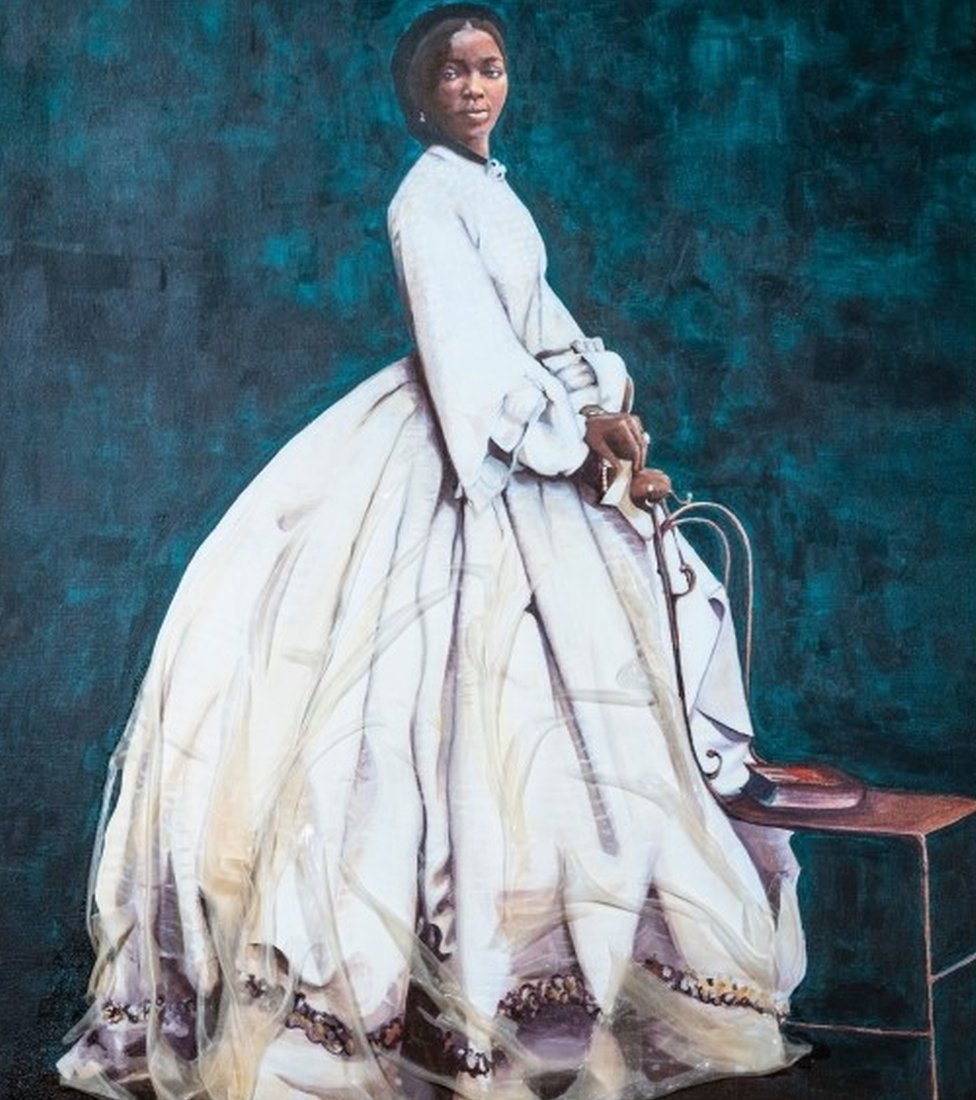

As part of its new project to highlight forgotten Black stories and figures in British history, English Heritage has unveiled a portrait of Bonetta, originally named Aina. The portrait, created by artist Hannah Uzor, was commissioned on Wednesday and is based on a photograph of Bonetta in her wedding dress, which is housed in the National Portrait Gallery in London.

The painting will hang throughout October (Black History Month) in Osborne House — Queen Victoria’s home — where Bonetta spent some time with the monarch before her death.

“To see Sarah return to Osborne, her godmother’s home, is very satisfying, and I hope my portrait will mean more people discover her story,” Uzor said in a statement.

“What I find interesting about Sarah is that she challenges our assumptions about the status of Black women in Victorian Britain. I was also drawn to her because of the parallels with my own family and my children, who share Sarah’s Nigerian heritage.”

Born into a royal West African dynasty, Bonetta was captured by King Gezo of Dahomey during a slave-hunt war in 1848. Her parents were killed in the war, and as a daughter of an African chief, Bonetta was kept in captivity as a state prisoner.

Being the princess of the Egbado clan of the Yoruba people, she was to be presented to an important visitor or sacrificed after the death of a minister or official to become their attendant in the outside world. In June 1850, when she was around eight years old, Bonetta was rescued by Captain Frederick E. Forbes of the Royal Navy whilst he was visiting Dahomey as an emissary of the British Government. Forbes asked the king for the little girl to be given to Queen Victoria as a gift.

“She would be a present from the King of the Blacks to the Queen of the Whites,” Forbes said. The king granted his request and she was brought to England. She was given the names Forbes Bonetta, after the Captain and the ship.

Bonetta initially stayed with Forbes’s family, before being taken to Windsor Castle on November 9, 1850. She was received by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. The Queen handed Bonetta over to the Church Missionary Society and paid for her education.

Bonetta, a year after, developed a cough believed to be caused by the climate of Britain. The Queen made arrangements for her to be sent to Sierra Leone for a better climate. There, Bonetta attended the Female Institution in Freetown. But at the age of 12, the Queen ordered Sarah to return to England, where she was placed under the charge of the Scheon family at Chatham.

Bonetta grew to be very intelligent and developed a particular talent for music. Her academic prowess won the Queen’s admiration to the extent that she gave her welfare allowance and allowed her to pay regular visits to Windsor Castle.

In 1862, Bonetta married James Pinson Labulo Davies, a 31-year-old Yoruba businessman who was living in Britain. The two came back to West Africa and settled in Lagos, where her husband became a member of the Legislative Council from 1872-74. Sarah also began teaching in a school in Freetown. She gave birth to a daughter and was granted permission by the Queen to name her Victoria. The Queen also became her Godmother.

In 1867, Sarah visited the Queen with her daughter and returned to Lagos, where she had two more children. Following the climate change between Africa and Britain, Sarah’s cough returned. She passed away in her 40s in 1880 after suffering from tuberculosis and was buried in Funchal, Madiera.

Her daughter, who was equally brilliant, was taken care of by the Queen and was still allowed to visit the royal household throughout her life.

In her lifetime, Bonetta was described by Captain Forbes as “far in advance of any white child of her age in aptness of learning, and strength of mind and affection.”

English Heritage’s project, apart from featuring Bonetta’s story, will also spotlight other Black figures who have been overlooked including Rome’s African-born emperor, Septimius Severus, and Dido Belle, the biracial great-niece of Lord Mansfield.