Thomas Klassen, York University, Canada

A refrain of American politics is the lack of representation of women, Blacks and Hispanics in the political arena. But almost as striking in 2020 is the exclusion of young people.

Those at the highest levels of the American government have never been older: Joe Biden, the next president, is currently 77 and will celebrate a birthday later this month. Nancy Pelosi, speaker of the House of Representatives, is 80. Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell is 78. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts is young by comparison at 65, but four of his eight colleagues are older than him.

It hasn’t always been this way. John F. Kennedy, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama began their terms of office while in their 40s. In contrast, Donald Trump was 70 when he assumed power in 2016 and Biden will be 78.

The age of those holding executive, legislative and judicial power in Washington, D.C., sends a warning. American politicians are much more generous to the old than they are to the young. After all, the country does have public health care, but only for those 65 and older.

Social Security retirement benefits are the third rail of politics that few politicians dare touch. Among the most feared, fierce and well-funded lobby groups in Washington is the American Association for Retired Persons, known as AARP, which advocates for the interests of those 50 and over.

Banned mandatory retirement

The aging of the political class illustrates how (old) age is now accepted in workplaces and more generally in the public domain. The U.S. was the first country to ban mandatory retirement at age 65. This ensures that workers are judged not on their chronological age but, rather, on their performance.

Like politicians, the vast majority of Americans now work in the services sector where most jobs place a premium on social competencies, knowledge and the ability to continue learning, rather than on physical strength.

Whether in politics or outside it, long careers also mean more experience, connections and opportunities to call in favours. Biden ran for president in 1988 and 2008, served for 36 years in the Senate and was Obama’s vice-president for two terms. McConnell was first elected to the Senate in 1984, and Pelosi to the House of Representatives in 1987.

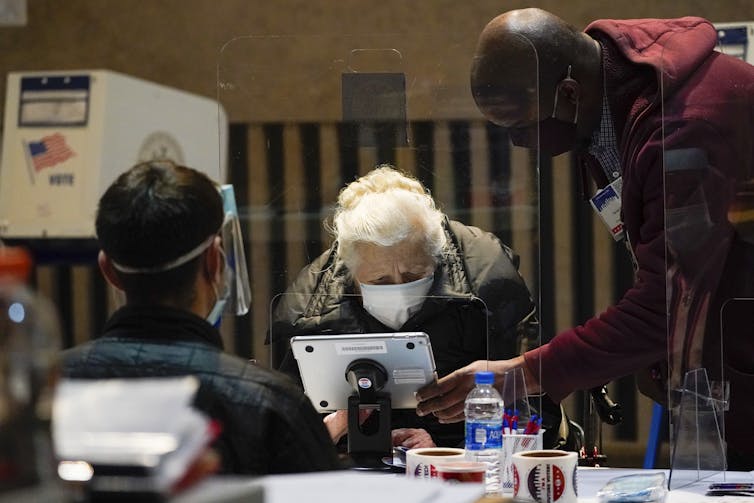

Older politicians have an advantage at the polls because their fellow older citizens are much more likely to cast a ballot than the young. For presidential elections, more than 70 per cent of the electorate age 60 and older casts a vote, but less than 50 per cent of those 18 to 29. This pattern did not change in 2020. Although youth turnout was higher for the 2020 election than in 2016, it is estimated that only half of those aged 18 to 29 cast a vote.

Not only are older citizens more likely to vote, but there are more of them in the United States than ever before. Half of those who vote in elections are over 50.

As such, the abundance of powerful older politicians in Washington comes as no surprise.

‘Sleepy Joe’ slur failed to take hold

Perhaps because older people have been so successful in politics, ageist stereotypes were largely absent from the recent presidential election. Although Trump sought to portray Biden as “Sleepy Joe,” this never gained traction among most of the electorate.

If 65 is the new 55, then in politics, 75 seems the new 65. The very notion of “old,” in fact, is under revision and reconstruction. After all, women regularly give birth in their 40s and in some cases even later.

But intergenerational conflict may nonetheless grow in America in the post-pandemic era when difficult decisions and trade-offs will have to be made. Older voters will fight to protect Social Security and Medicare entitlements, and more generally, the well-being and safety they have earned. Reforms that older voters demand are typically gradual in nature.

Younger voters have different political interests and are less loyal to established traditions. Young people are much more affected by political decisions surrounding drug use, abortion and crime and want to see rapid reforms. America’s young adults will demand action on creating and protecting jobs, ensuring educational opportunities and dealing with injustice.

It remains to be seen if Washington’s gerontocracy, headed by Biden, will be able to reconcile the priorities of the young with those of the old. The president-elect has successfully enticed more young people to participate in politics, but it’s far from certain that he’ll serve their interests.

Thomas Klassen, Professor, School of Public Policy and Administration, York University, Canada

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.