Ksenya Kiebuzinski, University of Toronto

Libraries have always been places of knowledge. For many of us, they offer insight into the socio-cultural and political changes happening around the world. I see this regularly as a librarian developing collections in Slavic and East European studies for the University of Toronto Libraries.

The content on library shelves reflects the culture around us. It may mirror changes in ideologies, popular culture and political leadership. Consider the many White House memoirs and exposés that were published during Donald Trump’s presidency. And think about all the fiction, poetry and graphic novels inspired by COVID-19.

Literature also plays a significant role in times of war. It can be used to justify or oppose conflict. Such content can take the form of scholarly analysis, journalistic investigation, fictional musing and even propaganda.

Information as weapon

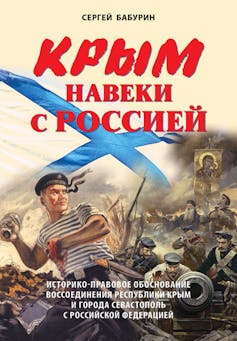

I became acutely aware of propaganda beginning in 2014. Russian books shipped to Toronto brought the faraway politics of Moscow to my desk in a very real way. The university library received works titled Crimea Forever with Russia, Ukraine: Chaos and Revolution as Weapons of the Dollar and The Battlefield is Ukraine: The Broken Trident.

The authors of these books made historical and legal arguments for the reintegration of Crimea with Russian. These publications deny or ridicule the existence of a Ukrainian state and nation with its own distinct language and customs. They blamed the U.S. and NATO for backing the Orange Revolution and Maidan Uprising to break up the “Russian World.”

Ukraine’s State Committee of Television and Radio Broadcasting reviews and restricts content deemed “anti-Ukrainian.” There are currently 300 titles on the committee’s list of publications aimed at “eliminating the independence of Ukraine.”

Chytomo, an online media outlet that covers publishing in Ukraine, has compiled and published a subset of the fifty most egregious examples.

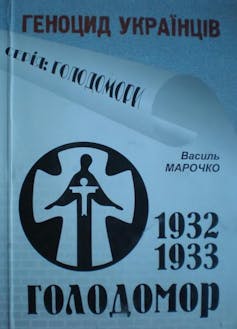

Ukraine is not alone in censoring literature. Russia’s Ministry of Justice maintains a federal list of extremist materials. It includes over 5300 articles, books, songs and other online content. Works considered extremist include texts critical of Russian authorities, publications by Muslim theologians, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Scientologists and content related to Ukraine. Banned Ukrainian books cover topics such as the Holodomor and 20th century Ukrainian liberation movements.

Propaganda in university libraries

The University of Toronto Libraries are not alone in holding copies of books banned by Ukraine or Russia. According to WorldCat, 44 out of 50 titles on Chytomo’s list are held by more than one library in North America. These titles are in the most prestigious academic libraries in the United States, such as Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Stanford, the University of Chicago and Duke.

Additionally, members of the East Coast Consortium of Slavic Library Collections acquire and preserve materials that have been banned in Ukraine and Russia.

Libraries emphasize free and equitable access to information and strive to build balanced collections. The professional code of ethics requires librarians to respect intellectual freedom, which is the right of every individual to seek and receive information from all points of view without restriction. We reject restrictions on access to material based on partisan or doctrinal disapproval, whether by individuals, governments or religious and civic institutions.

Hitler’s Mein Kampf or the collected works of Stalin can serve as primary sources to study society at a particular moment. Inflammatory material of the present serves the same function.

Mel Bach, a librarian at the University of Cambridge, writes that libraries “buy material that is distasteful and worse, from around the world, giving readers present and future the chance to study the extremes that are, devastatingly, part of reality.”

Purchasing such material does not mean that libraries approve of the contents.

Dealing with disinformation

Dealing with propaganda in its most injurious form — disinformation — requires that students and researchers possess information literacy skills. These skills include the ability to locate, critically evaluate and effectively use information to create new understandings of the world around us. Mastering these competencies will help people distinguish valid or trustworthy facts from ones that intend harm or spur violence.

The Russian government’s use of anti-Ukrainian disinformation to justify its war has led to civilian deaths, massive destruction and the threat of nuclear devastation. Numerous libraries, book collections and other cultural sites have been damaged or lost.

Placing propagandist works on bookshelves next to scholarship on similar topics can lend legitimacy to disinformation and war propaganda. People may develop beliefs based on what information is available to them and eventually accept that information as fact.

Laura Saunders of Simmons University succinctly sums up the ethical question of libraries and weaponized information. She asks “whether there are better or more responsible ways of collecting, organizing and making accessible information that is known to be inaccurate or discredited so that it is not being censored but also is not being promoted as a legitimate or authoritative source.”

Librarians have a responsibility to teach their users to evaluate the credibility and validity of information. We should verify that the information added to our library shelves is trustworthy and help introduce healthy scepticism into their critical thinking to uncover the biases and motivations behind the content we offer them.![]()

Ksenya Kiebuzinski, Slavic Resources Coordinator, and Head, Petro Jacyk Resource Centre, University of Toronto Libraries, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.