Does glitter bring to mind the prospect of shiny, sparkly, Christmassy, harmless fun? I’m afraid it is a bit more complicated than that. The popularity of glitter and the sheer volume used at Christmas presents us with a growing problem. Here are five reasons to rethink your glitter habit.

1. All that glitters is … plastic

Millions of items are adorned with glitter, from baubles to wrapping paper. Christmas is not Christmas without sparkly accessories and flamboyant decorations, but is it really? Modern glitter originated in 1934, when an American farmer named Henry Ruschmann created a way of cutting mylar and plastic sheets into tiny shapes. He formed Meadowbrook Inventions, which today is still one of the main global suppliers of glitter.

The majority of commercial products that contain glitter, whether these are single use items, such as Christmas cards, or more permanent items such as Christmas tree decorations, use inorganic glitter – chiefly plastics such as polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and also polyvinyl chloride (PVC). Glitter is usually layered with other materials, such as aluminium to provide extra sparkle. Underneath the microscope, it is possible to see the huge variation of glitter shapes and sizes: hexagons, squares, rectangles and even hearts and stars ranging from 6.25mm to a truly tiny 0.05mm.

2. Glitter is not fabulous (for marine life)

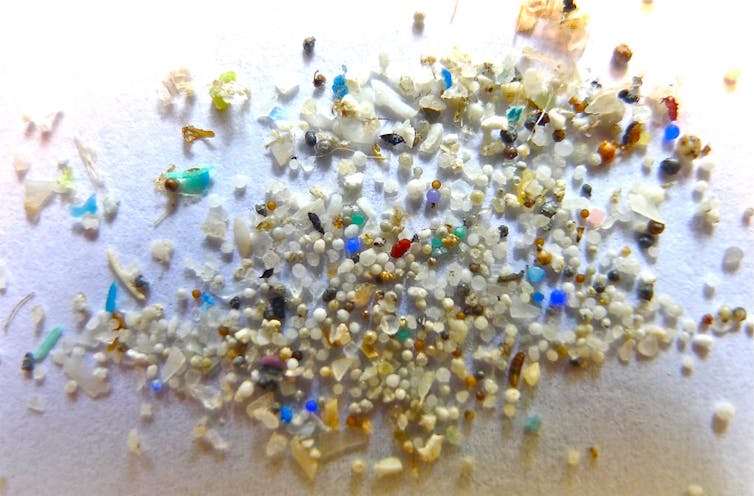

Most people now understand that microplastics, such as fibres from clothes or microbeads in facial scrubs, are dangerous to sea life. Glitter is a microplastic too, classed as a primary type of microplastic as the particles are less than 5mm in size and have been purposely manufactured to be of microscopic size.

Glitter can enter seas and oceans from rivers, via wastewater from our homes and via run-off from landfill sites. Although many microplastics are removed at wastewater treatment plants, a huge amount of microplastics still find their way through to the oceans. The size of these particles means they are easily consumed by small marine organisms, who cannot discriminate between particles of food and plastic.

Microplastic particles attract inorganic and organic chemicals to adhere to them, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB’s, which have been banned since 1979) and toxic heavy metals. A big risk to wildlife comes from the bioaccumulation of these toxins in the food chain – as recently highlighted in the final episode of the BBC’s Blue Planet II television programme on Earth’s oceans, which showed how young dolphins have been found dead, possibly killed by toxins accumulated in their mother’s milk.

3. Glitter is not just for Christmas

Microplastics break down under UV light which changes the structure of the plastic, by the mechanical action of water and by microbes. Some plastics such as PVC contain plasticisers, which can extend the degradation time of plastic. Given that plastics already may take hundreds, possibly even thousands of years to decompose, this is a concern. Glitter, like any other plastic, will degrade in the marine environment into further smaller pieces, called secondary sources of microplastic, but while it may grace your Christmas card only for a few weeks, it will hang around for much longer.

4. Glitter is hard to dispose of

Knowing the problems posed by glitter, you may be wondering what now to do with it all. This is a difficult question to answer, as whichever way you dispose of it there is a chance it will end up in the oceans. Most importantly, do not wash glitter down the sink. Instead, try reusing the glitter (or item adorned with it) for a future festive project. This still does not eliminate the risk, merely potentially prolonging the moment it enters the ocean. So what to do?

Where possible try not to buy cards or paper that features glitter, or make-up containing glitter particles. Nurseries in Dorset have already banned the use of glitter – could you do without it too? Ultimately, the only way to prevent this type of plastic adding to the global microplastic problem is to get rid of it completely, and opt for an eco-friendly alternative.

5. There are guilt-free glitter alternatives

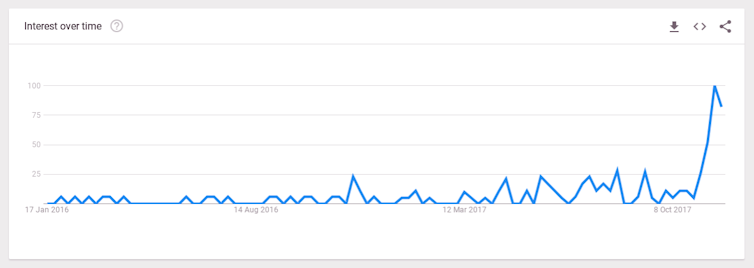

In line with the 2017 ban on microbeads in toiletries, there have recently been calls to ban glitter.. This has been met with some resistance and accusations that this represents scientists “wanting to take the sparkle out of life”. But we don’t have to go all the way from bling to bland.

Just as manufacturers of facial scrubs are looking at using natural exfoliating materials, such as apricot or walnut husks, glitter manufacturers have now started producing biodegradable glitter, available from many online stores (such as Glitterevolution and Ecoglitterfun). Biodegradable glitter is made from the cellulose of plants, such as the eucalyptus tree, grown on land unsuitable for food crops using sustainable forestry initiatives that require little water. On top of that, it is also compostable – truly an eco-glitter.

Even the company where modern glitter was born is getting environmentally friendly: Meadowbrook Inventions also now supplies biodegradable glitter, which means that with such a major supplier on board, there is hope for sparkly yet environmentally friendly Christmases in the future.

Author:Claire Gwinnett: Associate Professor in Forensic and Crime Science, Staffordshire University

Credit link:https://theconversation.com/five-things-to-consider-about-glitter-this-christmas-89519<img src="https://counter.theconversation.com/content/89519/count.gif?distributor=republish-lightbox-advanced" alt="The Conversation" width="1" height="1" />