Matthäus Tekathen, Concordia University

These are tough times for business owners due to the COVID-19 crisis. Experiencing substantial declines in sales or even a complete suspension of operations, they face cash-flow insolvency threats.

Indeed, a recent survey of small Canadian companies by the Canadian Federation of Independent Business found that 30 per cent won’t be able to keep their businesses afloat for more than a month if current conditions remain. Why?

The immediate problem

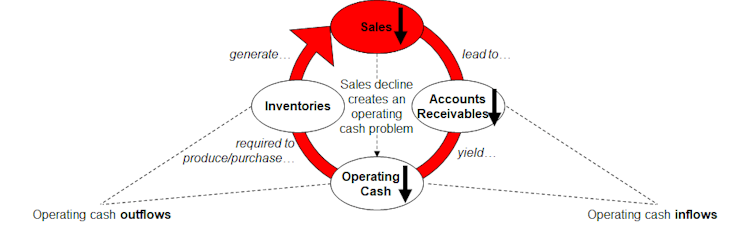

When sales drop, the cash wheel, whose function is to generate the required liquidity to operate the business, slows down or even comes to standstill. See below:

The more sales drop, the more the inflow of operating cash dries up. If business owners cannot slow down, at a similar speed, what are known as cash outflows — payments for salaries, raw materials or merchandise, supplies, interest, rent and the like — eventually cash reserves and subsequently credit lines will be used up. A cash-flow insolvency ensues.

‘No sales without costs’

Business owners know well: No sales without costs.

A retailer needs to purchase merchandise to sell it. That costs money. But unfortunately, the inverse — “no costs without sales” — usually does not hold. Why? For two reasons: fixed costs and a time delay.

Conceptually, there are variable and fixed costs. If sales drop, variable costs drop because lower sales volumes require, in total, fewer materials and labour and therefore fewer payments.

Yet fixed costs remain in place and are more difficult to alter in the short term. Business owners still need to pay rent, even for a closed store. Depending on the company’s cost structure, it will therefore have more or fewer possibilities to reduce cash outflows immediately.

Nonetheless, even variable costs will not disappear. Impacted business owners experience a sharp and rapid sales decline. But to offer goods for sale today, they must already have them in stock. There is a time lag: with payment terms of 30 days, say, last month’s bills must still be paid now and in the next few weeks.

Another large cost factor are labour costs. Wages need to be paid. Even with tough decisions to lay employees off quickly, two weeks of salary might still be owed. And at the end of the month or quarter, more bills come in.

As payments neither automatically nor immediately stop when sales stop, instant action is necessary to prevent cash-flow insolvencies. That’s why federal, provincial and local governments announced massive liquidity support for business owners.

What else can business owners do?

The best scenario for business owners would be if sales returned soon, since they fuel the cash cycle. Wherever possible, business owners search for creative ways to compensate for sales declines by finding alternative sales channels, such as online sales or home delivery options.

However, in many cases the services or products offered don’t allow for this quick shift. And so, besides working on getting sales back, business owners need to flatten or reduce the cash-flow gap to buy themselves some time, as visualized below:

The left side shows a simplified, healthy cash-flow state before the crisis. Cash comes in and out.

The middle illustrates the situation when the sales crisis hits. Cash inflow drops, and if cash outflow does not follow suit, we are in the cash-flow insolvency scenario.

To prevent this, business owners need to reduce the cash-flow gap as depicted on the right through measures that increase cash inflows or reduce cash outflows.

Closing the cash-flow gap

That means collecting payments from customers faster, retrieving financial resources from banks, restocking the cash balance through proprietary capital or obtaining government aid.

Postponing the payment of bills, renegotiating payment terms with suppliers, asking for deferrals, halting discretionary spending, downsizing or even closing the business temporarily are some other measures that can lower cash outflows. But before taking those measures, a quick cash diagnosis helps.

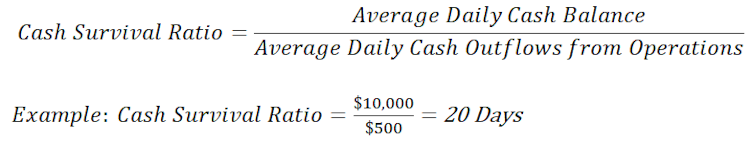

The tool that provides clarity about a situation’s severity is the cash budget, and the indicator that alarms business owners is the cash survival ratio, also know as cash buffer days. It forecasts how many days the business can survive without injecting new cash:

Because cash payouts aren’t evenly distributed from day to day, the cash budget is crucial to identify, proactively, cash bottlenecks before it is too late.

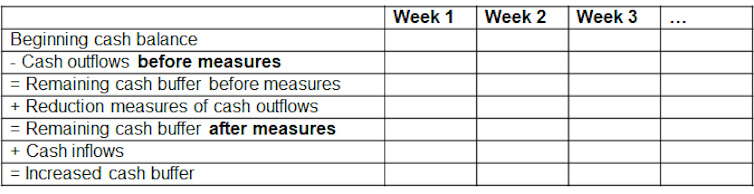

In the current context, modifying the cash budget’s structure, as shown below, makes improvements to increase the cash balance immediately visible. It’s a simple tool to help business owners navigate through the cash crisis by identifying, planning and forecasting their company’s immediate cash situation.

Overall, a company’s cost structure can accelerate cash flow troubles, and the time lag involved in adjusting outflows adds to the financial woes. Furthermore, while usually regarded as an inefficiency to be removed, having large cash buffers serves in these tough times as a valuable safety cushion.![]()

Matthäus Tekathen, Associate Professor in Accountancy, Concordia University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.