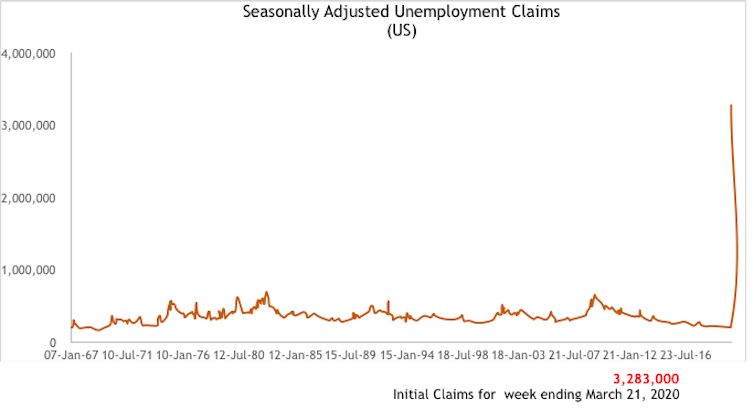

In all my years as an economist, I have never seen a graph like the one below. It shows unemployment claims in the US – observe the spike for the week ending March 21. The global financial crisis, the dot-com crash, Black Monday, oil price shocks, 9/11, none of these historic shocks are even visible in the graph.

The spike in unemployment claims is the proverbial canary in the goldmine. We should expect a swathe of bad economic numbers coming down the pipeline. The head of the St. Louis Fed expects a 30% unemployment rate and a 50% drop in US GDP by summer. More importantly, as the health crisis rises and crests at different times in different parts of the world, the horrifying numbers on GDP growth, unemployment, business closures are not likely to let up in the near term. Multiple countries are in a recession, and eventually, the whole world will fall into a deep recession.

The plunge from prosperity to peril will be as swift as the switch to lockdown protocols in most countries. We cannot even rely on the data we have to reveal the speed and depth of the crisis since this is collected and updated with lags. For instance, the US monthly jobs report for March collects data in the second week of March, failing to capture the massive spike in unemployment claims that appears after March 12.

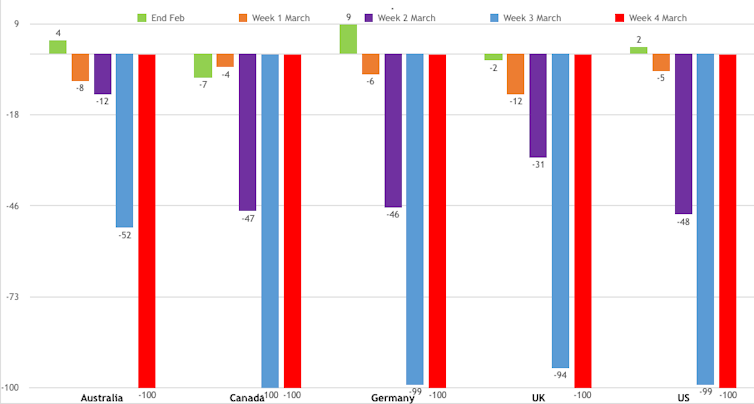

In the meantime, sources such as restaurant booking website OpenTable can offer some insights into the magnitude of things. The figures below show the recent plummet in diners eating at restaurants in four countries. Observe a sudden stop in the entire restaurant industry by the third week of March.

Combine a black swan event with missing data, and it is not surprising that markets are swinging violently.

Deep freeze

The question is not one of whether we are in a recession – we are. The more pertinent questions are: how long it will last? How deep it will be? Who will be impacted the most? And how swift will the recovery be?

These questions are complicated and even top economists must admit a lack of confidence in their answers. We are not experiencing a standard downturn. Nor is it simply a financial crisis, a currency crisis, a debt crisis, a balance of payment crisis or a supply shock.

We have not seen anything like this since the flu pandemic of 1918. Even there identifying the effects of the flu is confounded by first world war that took place at the same time. What we have here is something different. At its heart, we are experiencing a healthcare crisis with various parts of the world succumbing in a staggered fashion.

To slow down this global health crisis (the “flatten the curve” mantra), we have chosen to put the economy into deep freeze temporarily. Production, spending, and incomes will inevitably decline. Decisions to reduce the severity of the epidemic exacerbate the size of the contraction. While the initial decision to reduce labour supply and consumption are voluntary, this will likely be followed by involuntary reductions in both, as businesses are forced to lay off workers or go bankrupt.

Of course, government policies will attempt to mitigate these effects. Some are using traditional monetary and fiscal policies (cutting interest rates, quantitative easing, increasing unemployment insurance, bailouts). Others are trying out non-traditional methods (direct cash transfers, loans to businesses conditional on maintaining unemployment, wage subsidies).

Public health priority

How long the economic impact lasts depends entirely on how long the pandemic lasts. This, in turn, depends on epidemiological variables and health policy choices. But even when the pandemic ends, the resumption of normalcy is likely to be gradual. Countries will persist with a strict containment regime like in China today, and continue to impose travel restrictions to various parts of the world where the disease continues to spread.

The many factors at play in this complex, interlinked crisis that affects both people’s health and the global economy introduces massive uncertainty into anyone hazarding the pace, the depth and the length of the impact. As a result, we should treat any precise estimates (such as “GDP will decline by X%” or “markets have reached their bottom”) with scepticism.

Especially frustrating is the idea that there is a conflict between academic disease modellers and hard-edged economists saying that steps to slow the spread of coronavirus has trade offs. This could not be further from the truth. Among economists there is near unanimity that countries should focus on the healthcare crisis and that tolerating a sharp slowdown in economic activity to arrest the spread of infections is the preferred policy path. In a recent survey carried out by the University of Chicago, respondents universally agreed that you cannot have a healthy economy without healthy people.

The health crisis has naturally created a crisis of confidence. This, in turn, can have damaging long-term effects with continuing uncertainty leading firms and households to postpone investment, production and spending. Restoring confidence requires a singular focus on containing and reversing the spread of COVID-19.

Slowing the rate that people fall ill with COVID-19 is not the end in itself. It is a means to temporarily reduce the pressure on hospitals and give time to identify treatments and a vaccine. In the interim, we must build testing capacity, perform contact tracing, setup the infrastructure for extended quarantines, rapidly expand the production of masks, ventilators and other protection equipment, build and repurpose facilities into hospitals, add intensive care capacity and train, recall and redeploy medical personnel.

All of this is also the way to restore the economy’s health and economic policy must complement it. In the short run, economic policies should mitigate the impact of lockdowns and ensure that the current crisis does not trigger financial, debt or currency crises. It should focus on flattening the recession curve, ensure that the temporary shutdown has only transient effects, and facilitate a quick recovery once the economy is taken out of the deep freeze.

In the meantime, it’s important to also recognise that this is an unprecedented crisis. Everybody has their role to play, but nobody is infallible and uncertainty is inevitable.

Pushan Dutt, Professor of Economics, INSEAD

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.