Ribio Nzeza Bunketi Buse, University of Kinshasa

Arts and culture play an important role in all societies. They contribute not only to the social well-being of people but also to the social and economic development of countries. They generate incomes, as many case studies show, even if the level of informality of the sector in Africa tends to absorb that reality.

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development’s report on creative economy (2018), the global market of cultural goods and services doubled from US$208 billion in 2002 to US$509 billion in 2015. An Ernst & Young study (2015) indicates that cultural industries in Africa and in the Middle East are worth US$58 billion in revenues, employ 2.4 million people and contribute 1.1% to regional GDP.

Like all economic sectors, cultural and creative industries globally have been negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, specifically by the measures adopted by governments to limit the spread of the virus.

The impact has been well documented in advanced economies. However, data on the impact of COVID-19 on African cultural and creative industries is patchy.

According to Ernst & Young, the most lucrative of these industries in Africa are music, visual arts and movies. However, the low internet penetration holds back the rise of a promising sector such as online gaming. This in contrast with the high potential of the market. In fact, cultural policies are lacking or are not well implemented in many countries.

Using my experience in conducting an online survey in the Democratic Republic of Congo, I surveyed participants in the cultural and creative industries in six countries across four regions of sub-Saharan Africa.

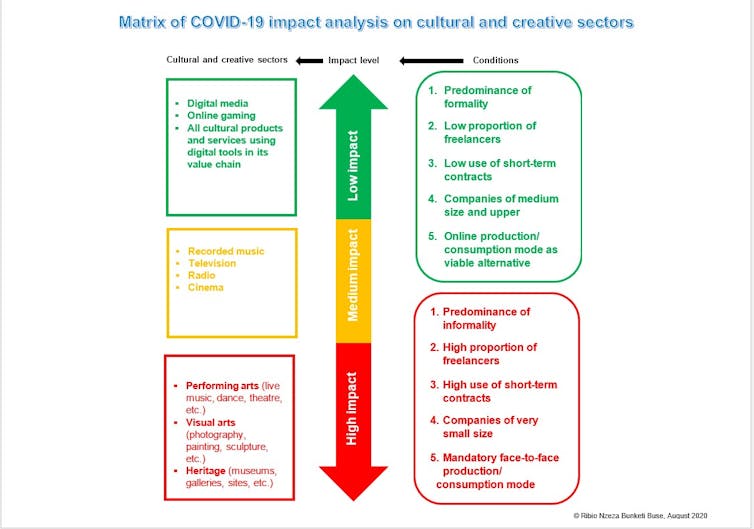

A matrix of economic impact of COVID-19 included in my study reveals there are several factors explaining the harsh impact of the pandemic on the cultural industries in Africa. These range from levels of informality and the size of companies to the types of contracts used and the modes of production and consumption in the industries.

The method

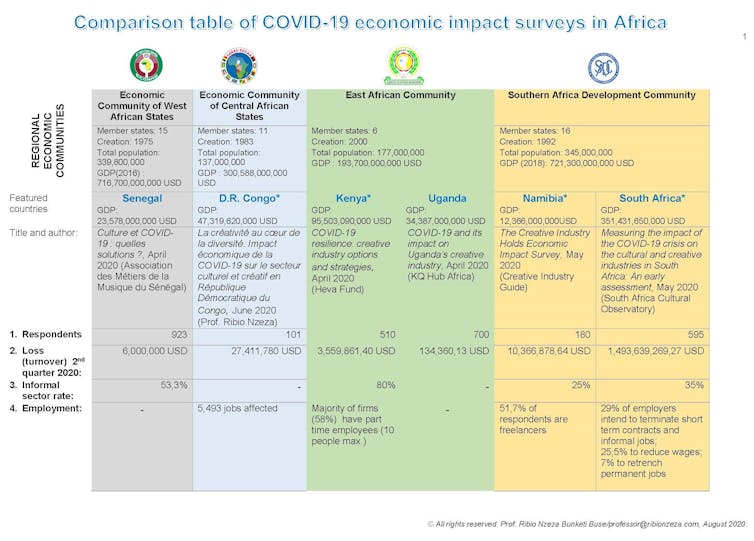

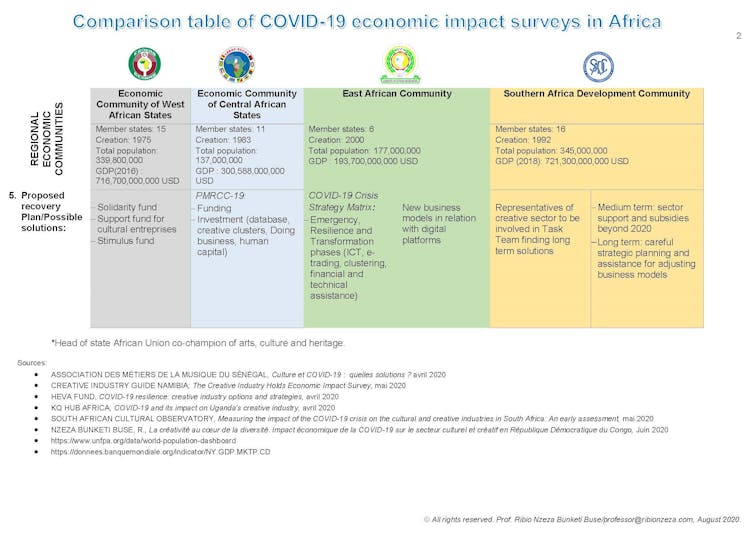

I compared quantitative studies available in four sub-Saharan African economic regional communities in order to map the numbers. These are the Economic Community of West African States (Senegal), the Economic Community of Central African States (DR Congo), the East African Community (Kenya and Uganda) and the Southern African Development Community (South Africa and Namibia). Those countries are the only ones that had available data resulting from completed surveys at the time of writing the research.

All of them were based on online surveys conducted during the various lockdowns that occurred between March and May 2020. Even if questionnaires were not the same in all countries, similar and recurrent entries offered a basis for comparison. They are, of course, early assessments as the pandemic continues.

The authorship of those studies is private (associations, firms, academics), except in South Africa with its South African Cultural Observatory, a public research centre hosted by the Nelson Mandela University.

Our research privileged quantitative data. Nevertheless, the qualitative data available – such as case studies – were mentioned. They have been produced by the Center for Strategic and Defense Studies of Ghana and by Circulador, a travelling research platform for lusophone countries (Angola, Mozambique and Cape Verde). An interactive map allows for visualising data.

Key findings

Financial losses (turnover) in the cultural and creative industries in Africa during the second quarter of 2020 vary significantly from one country to another. Figures range between US$134,360 for Uganda and US$1.49 billion for South Africa, respectively 0.002% and 1.7% as contributions to GDP. The combined turnover during the lockdown period of the six countries in which the online surveys were done comes to a total of US$1.5 billion.

The most affected subsector within the cultural industries in Africa was the performing arts – such as live music, dance, theatre and events. This is explained by the ban on gatherings in these countries due to the pandemic. The content subsector – audio-visuals, cinema, visual arts – came second.

The studies also shed light on the most profitable subsectors during this period. Digital media, online gaming, music and audio-visual content were able to be resilient. Their value chains – from creation to consumption – don’t require a high level of mandatory face-to-face interaction and effective use can be made of online tools.

Vulnerability

My study reveals that the vulnerability of African creative and cultural industries resulted mainly from five factors:

The predominance of the informal sector (53.3% in Senegal, 51.7% in Namibia, 80% in Kenya, 35% in South Africa).

The significant number of freelancers whose resources cannot withstand shocks (68% in Kenya). In Uganda, nearly 700 artists are affected out of 3,000 cancelled events.

The very small size of companies (47% of companies in DRC have between one and five employees; 80% have between one and 10 in Kenya). This is a further handicap because bigger companies are likely more resilient due to better access to financial, human and technological resources.

The prevalence of part-time jobs and short-term contracts (58% of companies in Kenya have part-time jobs).

The mode of production and distribution requires a high level of human interaction, especially for the visual arts (such as painting and photography).

Beginning of a journey

The pandemic has not only negatively impacted the creative sector in Africa, but it has also exposed its shortcomings.

To boost the cultural industries’ contribution to national economies, it is important to first conduct regular field studies to map the sector for oriented and efficient public and private interventions to enable the sector to recover from the setback of COVID-19. Governments have an important role to play in this regard.

It is well worth creating safer legal and business frameworks that will enable creative industries to operate more efficiently. Sound cultural policies along with implementation plans are key towards achieving this goal.

Ribio Nzeza Bunketi Buse, Associate Professor, University of Kinshasa

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.