Margaret Baguley, University of Southern Queensland and Martin Charles Kerby, University of Southern Queensland

The success of Disney’s 1964 movie Mary Poppins has often obscured the fact the popular series of books describing the experiences of the enigmatic nanny were in fact written by the Australian born author P.L. Travers.

Travers’ own sense of ownership of her creation in turn obscured the contribution made by the illustrator Mary Shepard. Despite a 54 year collaboration, Shepard is regularly ignored in discussions of the books: the 2013 movie Saving Mr Banks, which detailed the genesis of the film, did not even mention Shepard or the pivotal role she played in the books’ success.

Shepard was born in Sussex on Christmas Day in 1909, the only daughter of Florence Chaplin, a painter, and E.H. Shepard, who illustrated Winnie the Pooh and the Wind in the Willows. Her mother died suddenly in 1927, and that same year Mary was accepted into the Slade School of Art where she studied painting and drawing.

Even as a new author, Travers was never one to sell herself short, wanting E.H. Shepard to illustrate the first Mary Poppins story. He declined, too busy with other drawing commissions, but fortuitously Travers saw Mary’s artwork on a Christmas card and felt her whimsical style was well suited to her vision for Mary Poppins.

Shepard had recently graduated and was invariably humble about her talents. Travers was ten years her senior and far surer of herself. She saw the illustrations as servants of the text rather than artworks in their own right.

Read more: How Australia's children's authors create magic on a page

This view would colour their whole working relationship.

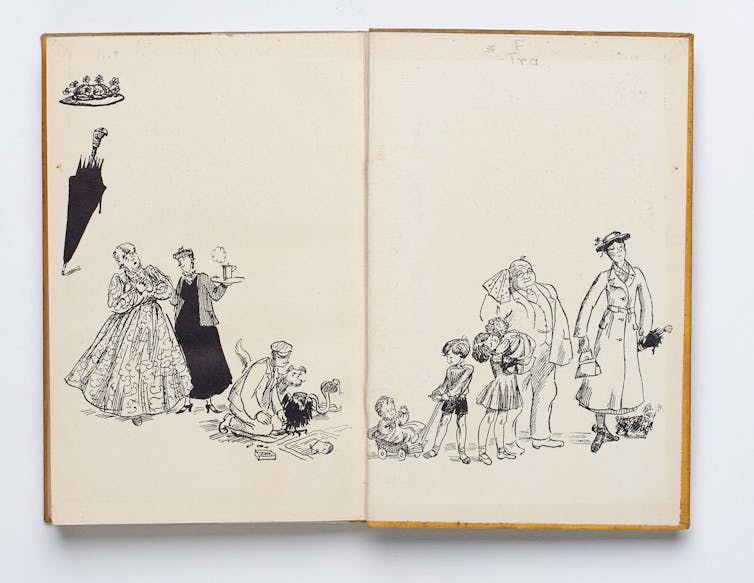

Years later, Shepard recalled the struggle to create an appropriate “Mary Poppins”. In her typically self-effacing style, Shepard wrote in her unpublished biography it was finally achieved “after some effort and a lot of help and advice from Pamela.”

The inspiration for Shepard’s initial sketches was a wooden Dutch doll owned by Travers.

Travers did not want Mary Poppins to be beautiful: Shepard wrote she was directed to make Mary Poppins “totally bosomless, as flat as a board, which as a character seemed to suit her best!”

But in later drawings there is a visual change, perhaps reflecting Shepard’s growing confidence. Poppins becomes prettier, more feminine, and eventually Shepard goes so far as to transpose her own features onto Poppins’ face.

A difficult relationship

Shepard’s family background and her humility were perhaps the main reasons why the long collaboration with the notoriously prickly Travers was even possible, with Shepard illustrating all eight Mary Poppins books from 1934 to 1988.

But Travers’ desire to exert artistic control is evident in letters and notes on Shepard’s preliminary sketches.

Writing about their relationship in 1980, Travers said: “the word, as it appears in print, needs to be served by both writer and artist, mutually and in harmony”. But closer to her real view was expressed in a letter to her agent, Harriet Wasserman: “what counts most is text, not picture”.

Ultimately, this ensured this long and financially successful collaboration with Shepard was often an unhappy one. Closer to the truth than Travers’ self-serving assessments is publisher Frank Eyre’s observation, that, because the character of Mary Poppins is so important:

Mary Shepard’s illustrations are of the first importance too, for they present Mary Poppins to us visually in a way that establishes her for ever.

The £1,000 feet

The relationship between Shepard and Travers came under particular pressure with the release of the Mary Poppins film.

Disney spent decades trying to reach an arrangement with Travers, and though Travers hated the film, it was – for her and Disney at least – financially very lucrative.

Shepard did not initially receive any financial benefit from the film, nor was Travers supportive of her efforts to do so.

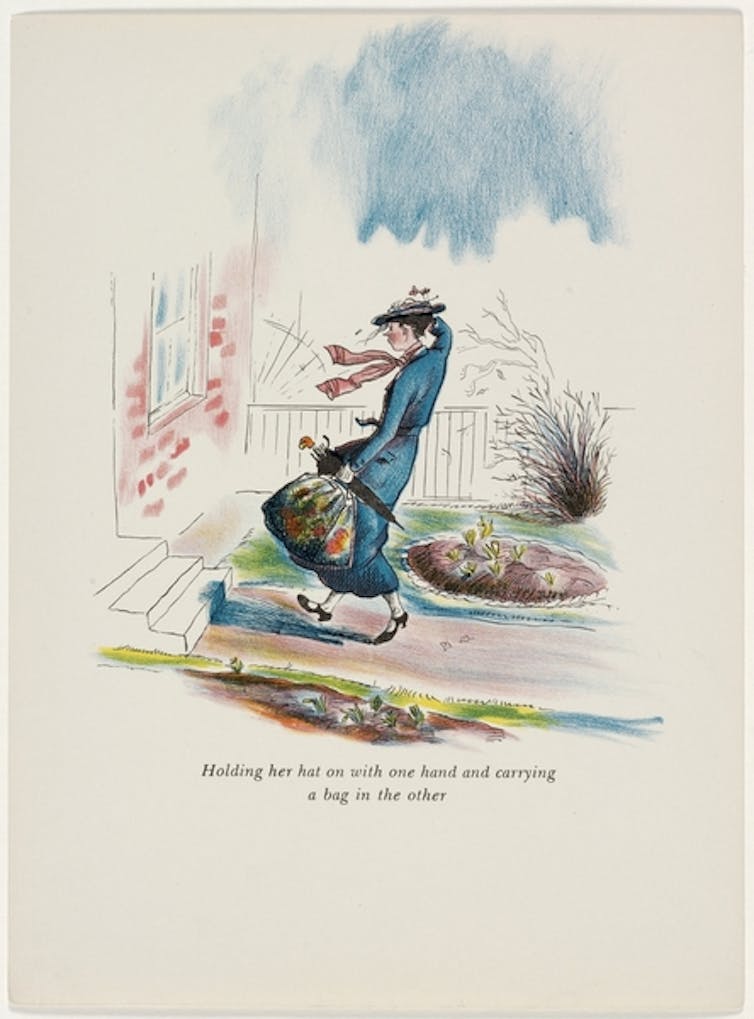

Her agent A.S. Knight finally succeeded in winning Shepard £1,000 for the unique portrayal of Mary Poppins’ feet in the first ballet position as she descends from the sky.

The placement of the feet, which Shepard described as portraying the “firm implacable stance which seemed to indicate Mary Poppins herself”, was inseparably associated with her creation of Mary Poppins’ image.

I’ll stay till the wind changes

Shepard was a talented artist who also illustrated Ruth Manning-Sanders’ Adventure May be Anywhere (1939) and A. A. Milne’s Prince Rabbit and The Princess Who Could Not Laugh (1966).

In 1937, she married E.V. Knox, the editor of Punch magazine who her father worked for as an illustrator and political cartoonist. It was a happy union, with Knox often standing in as a model for Mr Banks in Shepard’s drawings.

Mary Shepard died in September 2000, and her grave is beside her stepdaughter the writer Penelope Fitzgerald, who was only seven years younger and to whom she was very close.

Fitzgerald’s headstone depicts a hand with a pen. Shepard’s has a hand holding a paintbrush. A fitting tribute.

Margaret Baguley, Professor in Arts Education, Curriculum and Pedagogy, University of Southern Queensland and Martin Charles Kerby, Associate Professor Curriculum and Pedagogy, University of Southern Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.