Ahmed I Samatar, Macalester College

There are many attributes that capture Somali identity, however none seem so deep and abiding as these two: constant hyper anxiety over scarce rainfall, and uncommon talent in poetic composition and artistic performance.

The first underscores the ecological brittleness of the Sahel landscape; the latter points towards Somali aesthetic creativity.

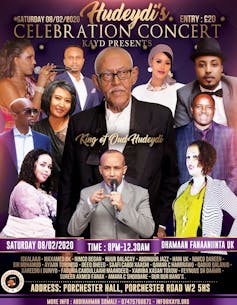

One of the most towering of these creative figures has passed – Ahmed Ismail Hussein, popularly known as Hudeide, commonly spelled ‘Hudeydi’ in the West.

Hudeide was a cultural icon, creator of songs loved by the nation and a touchstone in the making of modern music in Somalia. He died at 91 in London, after complications from contracting COVID-19.

I was fortunate to interview him in 2007, and immediately saw why Somalis everywhere found the man enchanting: tall and handsome, a deep voice, a mixture of playfulness and seriousness of artistic purpose.

Nation of bards

The composer and performer took an eminent place in a long tradition.

Historically known as a ‘nation of bards’, iconic Somali poets include the likes of Raage Ugaas, an erudite composer in the 1800s versed in local folklore.

In the 1900s, figures such as Mohamed Abdille Hassan, Abdillahi Sultan “Timacade” and Abdullahi Maalin Ahmed “Dhoodaan” were exemplars of bold nationalist perspectives, supremacy in vocabulary, and storytelling rich in analogic thought and imagery.

Equally outstanding are the country’s musical talents. Among the greatest was the oud maestro Hudeide. The oud or kaman is a string instrument common in the Middle East, North and East Africa, and it’s sound is found at the heart of both classical and popular Somali music.

It was when Hudeide discovered the oud that his musical journey really began.

Early life

He was born in 1928 in the port of Berbara on the British protectorate of Somaliland into a family of low-level workers in the colonial administration. He started school in Aden, the bustling main port of the British colony of Yemen. 'Hudeide’ was a nickname given because he had come to Aden from a brief stay at Hodeida on the Red Sea coast.

Hudeide had always been attracted to the beat of the drum, partly from watching and following parades of colourful colonial soldiers, with their drums, that took to the streets of Aden. One day, a young Somali oud player came to town.

Hudeide was mesmerised by the skill and sound of the troubadour and at once became fixated. He bought an oud and began to pick up lessons here and there, followed, to the chagrin of his parents, by full absorption in the instrument.

He told me that his parents died in relative old age, still in great disapproval of his devotion to music.

Virtuoso of the oud

By the late 1950s, Hudeide moved to Hargeisa, the small headquarters of what was Somaliland.

Radio Hargeisa employed him. The only station in the territory, it was established by the colonial authority. Hudeide was a member of the official band that was assigned to arrange musical scores for songs submitted by distinguished composers and sung by elite singers. Within a few years he found himself in an archipelago of excellence among the senior musicians, loved by the oud players in particular.

There were a number of unique dimensions to his creativity that catapulted him to the forefront of the music world – and kept him there for decades. Perfect communication between his fingers, the strings and his ears; sheer dedication; and the audacity to strive for originality. They would produce what became the ‘Hudeide technique’, a new brand of oud playing. He inspired many generations and directly taught a few in the course of his long life.

Hudeide’s other rare artistic gifts included the composition of searing ballads that immediately became household phenomena. But his creative production had a wide range. It included political critique and patriotic messages. The famous Haudow Magaca is a moving nationalist composition accompanied by riveting manipulations of his oud strings that urges Somalis of the Ogaaden region to join the new Somali Republic. But it could just as easily include themes like sibling love or peace on earth.

A translation of his 1967 poem Uur Hooyo (Mother’s Womb) is a heartbreaking expression of the bond between brothers:

At the time of my death

It’s you who’ll place me

In the grave, and your hand

Throw the final soil.

My human inheritance

The one closest to me

The trials of the world

Have brought us apart.

I cannot endure

Being on my own

I sway with melancholy

I am no better off

Than a lone son.

Grounded cosmopolitan

In 1993, with the Somali republic in the midst of horrendous civil war, Hudeide settled into the secure but melancholy condition of the diaspora experience in London.

Once in a while, he met with other noted artists in exile, living in different parts of the city. He performed on special occasions and taught a few keen students, but mostly kept to himself.

In one of Hudeidi’s final creative moments, he ruminated on what it meant to be a citizen of a new country (Britain) and the larger global society – a kind of a grounded cosmopolitan. Meditating on the ugliness of possible nuclear war, the old oud maestro turned to writing apocalyptic poetry. A translation of Dhulka (Earth) opens with, “The Earth, the earth, the earth, the earth” and warns of global disaster. It ends with the lines

Don’t make the trumpets sound

Don’t bring the day of Judgment near.

Given the cruelty of COVID-19 isolation, Hudeide died alone.

But he left behind a reputation for the ages: durable and multifaceted talents, humane dispositions, enlightened engagement with others, and a universalist ethos.

He was an artistic pioneer of lasting and distinctive gifts, and bottomless stamina. He gave us over 70 years of high-octane performances.

We are grateful.

Ahmed I Samatar, James Wallace Professor of International Studies, Macalester College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.