Julia Petrov, University of Alberta and Gudrun D Whitehead, University of Iceland

“Beauty is pain,” goes the famous adage. The phrase suggests that in order to fully understand what a society considers beautiful, you must explore ugliness. Enter the horror movie.

Horror often examines “the dread of difference” seen in society, and cinema scholars like Barry Keith Grant have studied how horror films explore gender roles.

Women’s violent struggles as perpetrators and victims of horror — in the pursuit of sexual freedom, social empowerment and fulfilment of desire — are reflections of the concerns of a conflicted and changing society.

In the book we edited, Fashioning Horror: Dressing to Kill on Screen and in Literature we explored how horror literature, film and folklore are expressed through fashion and costume. Our approach was informed by our background in fashion studies, folklore and literature, as we investigated the central importance of clothing to the horror genre.

Here, we demonstrate how common fears around femininity are expressed through costume and roles in the movies.

The ghost

The well-known popular image of a haunting woman in white is a classic gothic and horror trope rooted in European folklore dating back to pre-Christian and pagan times. Whether dressed in the white of a burial shroud, or the white of mourning, “the White Lady” often appeared by moonlight.

The film The Ring (2002) based on the Japanese horror film of the same name derived from the novel by Koji Suzuki, shows a contemporary reading of the ghost as related to anxieties about new technology, social change and family relationships. The ghost in white is not seen by moonlight but by the blue glow of a television screen. Naomi Watts portrays a journalist who investigates a cursed videotape that seemingly kills the viewer seven days after watching it.

In 2008, designers Kate and Laura Mulleavy took inspiration from the white shirtdress worn by Sadako, the vengeful video ghost in the 1998 Japanese original film, for their Rodarte fall show.

The bride

In horror, the figure of the bride represents the thwarted promise of the virginal woman abandoned or killed before she was to be wed and is related to anxiety about domesticity. Bride of Chucky (1998) shows the depths to which two murderous dolls will go to turn human again.

Dolls have traditionally been used to instruct girls into their future roles as mothers and wives, and fashion dolls herald new trends. The doll in this movie presents quite a different set of possibilities for those who dare to play with her. Bored by expectations of conventional womanhood, both as a sex symbol and as a housewife, Tiffany (Jennifer Tilly) transforms herself into a Martha Stewart in the kitchen and a crazed serial killer outside the home. Barbie, eat your heart out.

The mother

Mothers subverting expected norms is a common theme in folklore and horror. In the film Ma (2019), actor Octavia Spencer plays a traumatized and psychopathic mother who locks up and drugs her daughter to keep her close. In the film, veterinary assistant Sue Ann (Spencer) is called upon by a group of (mostly white) teenagers to buy them alcohol; the teens nickname her Ma.

Spencer has noted that due to systemic racism, Black women in Hollywood have faced limited dramatic opportunities for roles that push the stereotypes of Black women as caregivers. The actor said one appeal of starring in Ma was pushing beyond that mould and subverting the idea of Black people dying at the beginning of horror films.

Read more: I am not your nice 'Mammy': How racist stereotypes still impact women

Viewers learn Sue Ann experienced humiliating teen years and what begins as apparent friendly support soon spirals out of control.

The film mines the hidden depths of Sue Ann’s resentment and fears for her own daughter as she seeks to avenge her own past. A classic transformation scene sees Sue Ann change from wearing mostly scrubs, a reference to self-effacing caregiving roles, into a glamorous outfit. Ma sits at her mirrored vanity table applying lipstick surrounded by red candles. “Pow,” she says to her reflection before heading downstairs to kung-fu kick a pyramid of beer cans.

Her retro looks include acid-washed denim, black lace, and leopard print. Through the lens of the teens who laugh at her and find her “uncool,” these outfits suggest society’s discomfort with women stepping out of their roles as matrons and caregivers to maintain an equal place in society.

The vampiress

The female vampire turns the notion of female sexuality on its head in horrifying ways. So popular was the archetype of the man-eater in early cinema, that the “vamp” became a recognizable look for fashionable silent film actresses like Theda Bara, Musidora and Nita Naldi.

The undead female vampire costumes herself for seduction and disguise. Consumption therefore takes on a dual role, unlocking anxieties about capitalism. The stylish film Only Lovers Left Alive (2013), featuring fashion icon Tilda Swinton, played with this by costuming her character in a mixture of old and new fabrics, with an emphasis on loungewear.

Swinton’s shock-blonde hair was supplemented by yak wool, further hinting at the not-quite-human nature of the vampire. Vogue even encouraged readers to “get the look.” Swinton presents a new type of vampiress; one not reliant on her sexuality to stand out. She has style.

The witch

Fears that women will escape patriarchy, particularly through sexual independence, underpin this mythology, and stories of witches can be both terrifying and empowering.

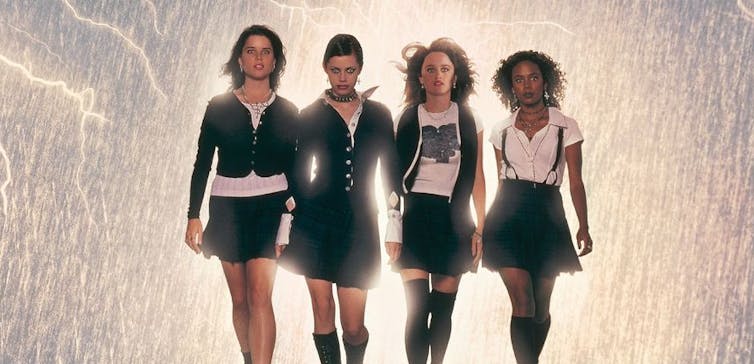

The 1996 film The Craft inspired a generation of teenage girls and included frank explorations of teen suicide, depression, racist bullying, sexual harassment and slut-shaming. Fairuza Balk plays the iconic teen witch Nancy Downs, an aggressive, angry goth girl, at odds with everyone outside her own small circle. As she gains in power, her appearance becomes wilder.

Films about witches remind viewers that alternatives to the

. The presence of chokers, chains, dark lips and short hair in the trailer demonstrates the continued relevance of punk and goth influences for rebellious teens.

The monster

The fear of a woman’s appearance hiding something monstrous is an ancient trope. From the ancient Greek gorgon, to the folk tales of many cultures featuring seductive female shape-shifting demons, female beauty has the potential to kill onlookers.

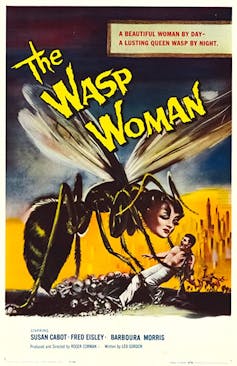

However, beauty may also come at a cost to the fashion victim, as seen in the morality tale of female vanity in Wasp Woman (1959).

The fear of female aging, as well as the perceived arrogance and aggression of female executives, underpins this story which is an imaginative take on the of royal jelly in cosmetics, still a cosmetic ingredient today.

The character Ms. Starlin (Susan Cabot) is depicted as one with an intemperate desire for youthful good looks, but she is inadvertently transformed into a hideous wasp woman. How similar is this tale, at its core, to the gleeful take-downs of women who have undergone botched plastic surgeries?![]()

Julia Petrov, Adjunct professor, Human Ecology, University of Alberta and Gudrun D Whitehead, Assistant Professor of Museology, University of Iceland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.