Catherine Clase, McMaster University; Charles-Francois de Lannoy, McMaster University; Ken G. Drouillard, University of Windsor, and Scott Laengert, McMaster University

Early in the pandemic, mask-wearing policies were consistently associated with decreased transmission of SARS-CoV-2. At that time, the masks worn were generally made of cloth and often improvised.

The highly-transmissible Omicron variant focused attention on mask performance.

Although most provinces are lifting official mask mandates, we agree with public health authorities in recommending that people wear the best mask available. We have been working to improve and test reusable masks for community use.

We are an interdisciplinary group of engineers, scientists, a doctor and a community mask-maker. We test novel personal protective equipment (PPE), advocate for mask use and summarize the best available evidence at clothmasks.org.

Hierarchy of mask performance

There is an accepted hierarchy of mask performance based on mask materials, certification standards and use, confirmed by a 2022 California population health study. The best protection is obtained by wearing a respirator such as an N95, CAN95 or CAN99, or in Europe, an FFP2 or FFP3. Performance is typically lower for KN95s, KF94s and certified medical masks meeting ASTM levels 1 to 3. (ASTM is an international standards organization.)

The materials used in all these masks offer similar, excellent, aerosol filtration, but the masks differ in their fit and seal on the face, with KN95s and KF94s fitting better than certified medical masks.

Cloth masks are typically ranked lower in their performance and may or may not be certified (for example, meeting ASTM-F3502 standard). However, we recently showed that well-fitted cloth masks comprising high quality two-ply cotton material can perform as well as Level 1 medical masks.

Fabric types

When health-care professionals are issued N95s or other certified respirators, they are fit tested to verify mask performance on the wearer. But fit testing is typically not an option for the public.

Our research, explained in plain language here, underscores that fit can be achieved by good design and is as important as mask materials. For our research, we adapted the same method used in quantitative mask fit testing: a PortaCount fit tester that counts particles inside and outside the mask.

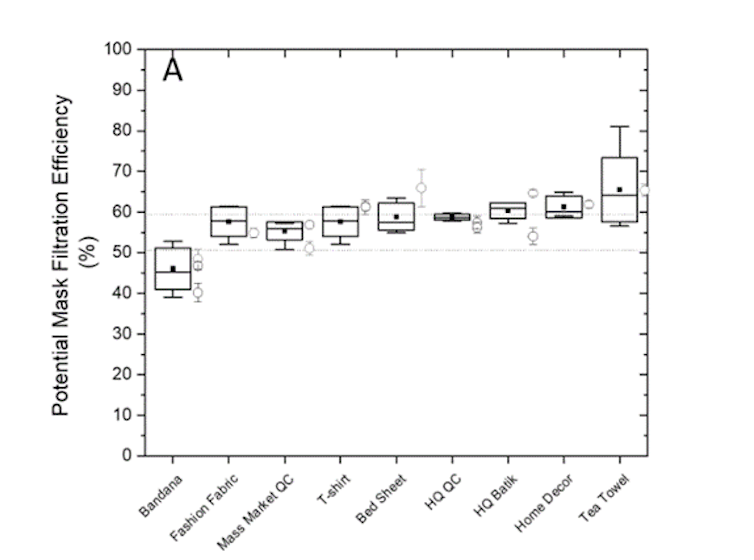

We tested 16 different cottons from nine recognizable categories. All except bandana cotton showed filtration equivalent to a medical mask. These findings apply to the carefully designed two-layer cloth mask with ties we used — other masks that fit less well will not provide the same protection.

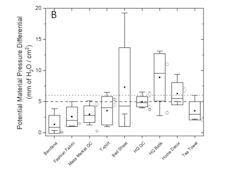

Our results show that two-layer cotton masks made from quilters’ cotton, fashion fabric and T-shirt fabric filtered 55 to 60 per cent of aerosol particles measuring one micron or smaller, the size relevant for infectious aerosol particles. This was similar to the performance of a Level 1 medical mask. The breathability of the two-layer cotton masks was also acceptable as per medical mask standards.

Filtration in the same range was provided by batiks, home décor fabric and bed-sheet fabric, but some examples of these materials failed the breathability testing. Tea towel fabrics also filtered well, but some were too thick to sew. Bandana fabrics performed worst at 46 per cent filtration.

Fit and design

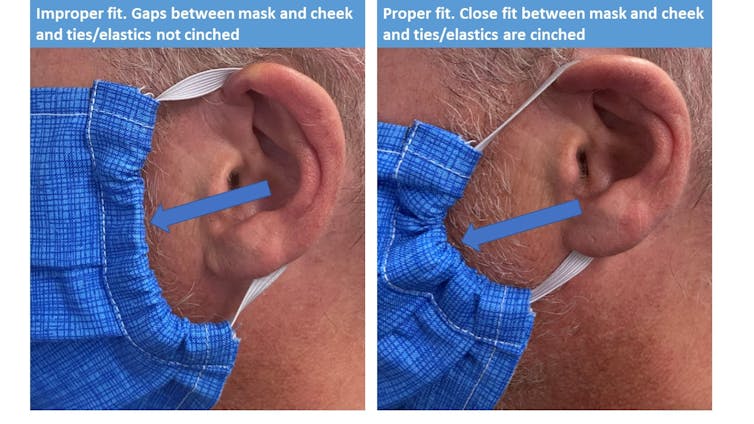

Our research showed that cloth masks performed similarly to medical masks because they fit better, were designed thoughtfully and had overhead ties. Although medical masks are composed of materials with better filtration performance, they exhibit greater leakage, with completely unfiltered air passing around the mask.

The cloth masks included in past studies may have been haphazardly selected: their filtration, using the same methods that we used, was found to be between 23 and 52 per cent. A thoughtfully designed two-layer T-shirt mask with overhead ties, tested on human volunteers, filtered 50 per cent of aerosols, in keeping with our study, and again highlighting the importance of fit.

To compare like with like, when we looked at other studies, the filtration percentages that we quote above were taken from studies using a similar design: protection of a human wearer, using particles 0.02 to 3 microns, 0.02 to 1 microns and 0.02 to 0.1 microns. Other studies examining source control, using mannikins and using larger particles come to similar conclusions.

Good masks fit well, with minimal obvious leaking at the edges. Nosewires, overhead ties or earloop adjusters all contribute to fit. Two layers or more, and a middle layer of non-woven polypropylene improve overall filtration.

Masks meeting the new U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention standard for community masks, ASTM-F3502, are likely to filter well, though generally not as well as respirators.

N95 masks

Hospitals report that the current supply of N95-type masks meets but doesn’t exceed demand, and supply of these masks is insufficient for the general population. Access and cost issues require public health and economic solutions along with consideration of environmental impact of disposable PPE.

If buying respirators for personal use, we recommend buying only what you need and practising extended reuse. If buying KN95s and equivalent certified medical masks, we advise paying close attention to the fit of the mask. We recommend double masking medical masks or using minor modifications or mask hacks that enhance fit and reduce leakage.

Carefully designed, well-fitting, multilayer reusable cloth masks still have an important ongoing role in reducing transmission of SARS-CoV-2, especially in lower risk settings.

Protection is highest and transmission is lowest when everyone wears masks, because masks both protect the wearer while also reducing the number of contaminated particles reaching the environment (source control). There are important reductions to individual risk from wearing any mask, which have been observed in the community and quantified in the lab. We can protect ourselves, others and vulnerable people. Let’s all wear the best mask available.

Rebecca Rudman, co-founder of the Windsor Essex Sewing Force and member of McMaster’s Cloth Mask Knowledge Exchange, and Amanda Tomkins, an undergraduate student in engineering at McMaster University, co-authored this article.![]()

Catherine Clase, Physician, epidemiologist, professor, McMaster University; Charles-Francois de Lannoy, Assistant Professor, Chemical Engineering, McMaster University; Ken G. Drouillard, Professor, Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research, University of Windsor, and Scott Laengert, PhD Student, Chemical Engineering, McMaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.