Jason Yosar, The University of Queensland

Nearly one-third of Australians aged 55 or over (or around 1.5 million people) have an untreated cataract. In 2013-14, there were 229,693 hospital admissions for cataract surgeries, making cataracts one of the most prevalent conditions among Australians.

Cataracts remain one of the leading causes of visual impairment globally; they are responsible for blindness in 20 million people worldwide.

What is a cataract?

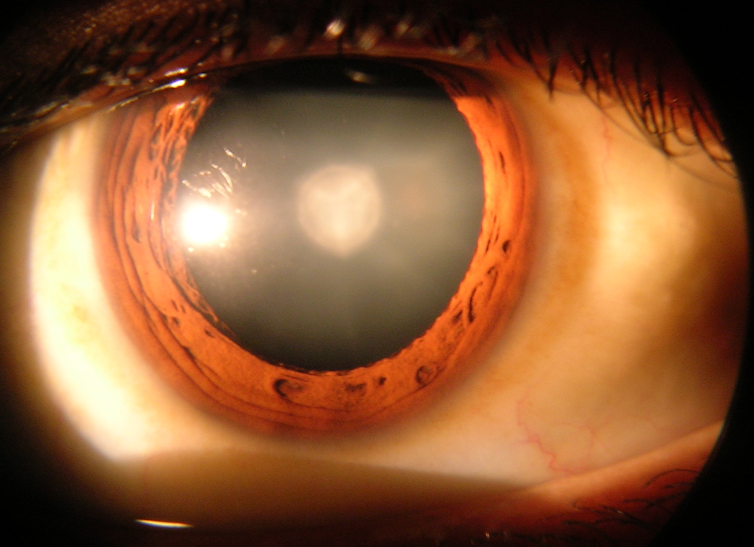

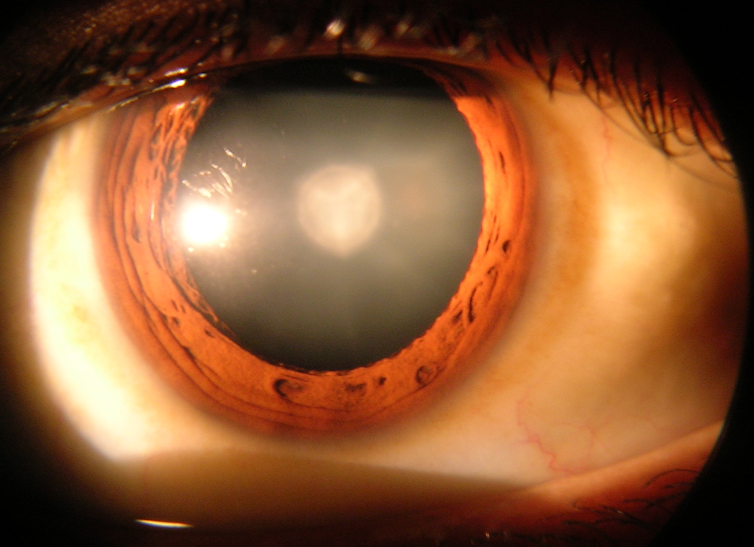

The word cataract comes from the Latin cataracta, which means waterfall. It is a clouding of the normally transparent crystalline lens in the eye.

The lens works together with the cornea to focus light onto the retina, which converts light to electrical signals that are transferred to the brain. This gives us the images we see.

Cataracts commonly cause blurring of vision, glare from bright lights – especially oncoming vehicle headlights – halos around lights, loss of colour saturation and poorer night vision. Affected people may notice they no longer need their reading glasses as a cataract causes a paradoxical increase in the focusing power of the lens.

Because cataracts develop slowly and painlessly, they may progress for many years before being diagnosed. If left untreated, however, they may eventually cause severe visual impairment in the affected eye. Cataracts commonly occur in both eyes but may occur in one eye alone, or progress at different rates in each eye.

What causes cataracts?

Cataract formation is part of the normal ageing process of the lens. More than 70% of men and women aged 80 and above will have a cataract.

The most common type of cataract is age-related, which is thought to occur due to breakdown and degradation of lens proteins over time. This process can be accelerated by smoking, chronic diseases, such as diabetes and high blood pressure, and exposure to ultraviolet light and radiation.

Less commonly, cataracts can occur following prolonged use of steroid medications, such as those taken for rheumatoid arthritis and other chronic inflammatory conditions. They can also occur following trauma or radiation to the eye.

A very small number – around 2.2 per 10,000 babies in one Australian study – are born with congenital cataracts. These usually occur on their own or uncommonly in association with other diseases, such as rubella infection.

How are cataracts treated?

No medications exist to treat a cataract or slow its progression. Stronger spectacles may be all that is needed to manage early cataracts. However, surgery may eventually be required as a cataract progresses and causes troublesome vision impairment.

Cataract surgery has been practised for thousands of years and has involved the same principle: removal of the cloudy lens. The Romans used to do this by inserting a sharp needle into the eye and rotating it.

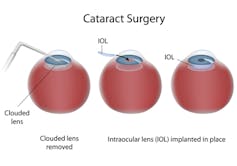

The most common type of cataract surgery performed in Australia is called phacoemulsification. Typically, an uncomplicated surgery lasts just under ten minutes and is done as a day procedure.

Local anaesthetic is used to numb the eye and a small incision is made through the front of the eye; a hand-held ultrasound probe then breaks apart the cloudy lens contents. This material is suctioned out of the eye and a plastic lens is inserted in its place.

Cataract surgery is one of the most frequently performed procedures in Australia and has a very high success rate.

Although very uncommon, complications can occur. These include retinal detachment, infection, incorrect refractive power of the lens, swelling of the cornea and dislocation of the newly implanted lens. These rare complications may require further surgeries or medications and could lead to permanent visual impairment in the affected eye.

Can we prevent cataracts?

The progression of age-related cataract may be slowed by wearing sunglasses when outdoors from an early age, avoiding smoking, carefully controlling blood sugar levels if diabetic, and consuming plenty of fruits and vegetables.

Antioxidant supplements are sometimes recommended for prevention of cataracts. Unfortunately, studies have shown these to be ineffective.

If you experience symptoms of a cataract, the first point of call should be an optometrist who can perform a bulk-billed eye examination and refer you to an ophthalmologist if a cataract is found.

However, wait lists for public hospital clinics may be lengthy (months, to over a year) for minor cataracts not severely affecting vision.

The author thanks Dr Cameron McLintock, ophthalmology registrar at Queensland Health, for his contributions to this article.![]()

Jason Yosar, Associate Lecturer, School of Medicine, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.