Padmashree Rida, Georgia State University and Ritu Aneja, Georgia State University

White women in the U.S. are slightly more likely to develop breast cancer than black women – but less likely to die of it. There has been a 35 percent decrease in breast cancer mortality rate from 1990-2012. The breakdown by race over this period, however, shows a different story. Death rates for black women decreased by 23 percent, while the death rates for white women declined by 42 percent.

A big, but not the only, reason for this is that white women tend to more frequently get two subtypes of breast cancers, called ER-positive or HER2-positive, for which we now have very effective targeted treatments.

Black women, however, are two to three times more likely than white women to get an aggressive type of breast cancer called triple negative breast cancer, for which there are still no approved targeted treatments. Researchers do not yet know all the reasons why this is so, but are looking for answers.

Research has vastly improved breast cancer treatments and survival rates over the years, with a five-year survival rate for localized breast cancer at 98.9 percent, but the gap in mortality rates between black and white women has stubbornly persisted.

We study breast cancer, with a special emphasis on health disparities. Here are some of the trends we see.

Disturbing numbers

First, some statistics that lay out the extent of the problem. About 1 in 8 American non-Hispanic white women, and about 1 in 9 African-American women will suffer from breast cancer in their lives.

While breast cancer is slightly less prevalent in African-American women, it is much more likely to be diagnosed at a later stage in them. About 37 percent of white patients and about 47 percent of black patients will have cancers that have spread from their breast to nearby lymph nodes at diagnosis. When the disease has spread, it typically presents a greater treatment challenge. In fact, the five-year survival rate for breast cancer patients with distant metastasis, or disease that has traveled to another organ such as the liver or bone, is 26.9 percent, as compared to 98.9 percent for those with a localized disease.

In addition, the aggressive triple negative type of breast cancer accounts for 12-20 percent of tumors in white women, but about 20-40 percent in black women. Triple negative breast cancer is particularly hard to treat because it does not respond to targeted treatments that have proven to be effective in treating breast cancers that test positive for certain receptors on cancer cell surfaces.

Internal environment

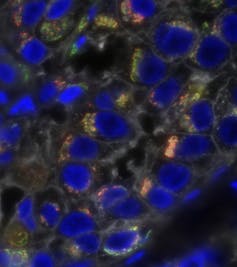

Beyond triple negative cancer itself, there also seem to be racial differences in what we call the tumor microenvironment of the cancer cells. Tumor microenvironment is the immediate cellular environment of the cancer cells, including surrounding blood vessels, immune cells, signaling molecules and the tissue matrix that surrounds tumor cells (i.e., the extracellular matrix). Since the tumor microenvironment can affect behavior of the tumor cells and their response to treatments, these racial differences could impact tumor biology and disease progression. Studies have also uncovered racial differences in gene expression patterns of cancer cells, in which genes are over-expressed or under-expressed in the tumor cells of black versus white women.

One of the common abnormalities found in cancer cells proliferating within tumors is that they often gain or lose stretches of DNA, which could include multiple genes, or even whole chromosomes that carry hundreds of genes. As a result, cancer cells may harbor higher-than-normal or lower-than-normal copies of genes compared to healthy cells. Daughter cells that arise from such cancer cells form a “clone of cells” that could be genetically different from other such clones within the tumor.

When this gain or loss occurs at a fast rate, it results in a tumor with astounding clonal diversity. Such tumors are more likely to harbor clones that can spread very efficiently through the body or resist treatments very staunchly, resulting in a higher risk of death for the patient. Scientists have discovered that breast tumors in black women tend to be more clonally diverse, and therefore harder to treat, than those in white women. The discovery of these biological factors is fairly recent, and research is still ongoing.

Beyond tumor biology

Having other diseases, such as diabetes, also could be not only a risk factor for developing breast cancer but also for poorer outcomes, research has shown.

Some statistics point to problems outside of the sphere of medicine, however.

In the U.S., about 23.1 percent of black women live in poverty, compared to 9.6 percent of white women. Studies have shown that a lack of resources makes a huge difference in survival rates, treatment responses, and progression of disease. Poor women are less likely to have good quality health insurance, to get as much information on early detection and screening, and to have access to the best health care and latest treatments.

Another factor, that is both biological and environmental, is obesity. According to the National Cancer Institute, fat tissue actually makes the hormone estrogen. Exposure to high levels of estrogen over a lifetime increases the risk of breast cancer.

Further, in the U.S., obesity is strongly linked to poverty, according to the National Institutes of Health. In other words, since black women are more likely to be poor, they are more likely to be obese – which makes them more likely to develop breast cancer.

The higher incidence of poverty among African-Americans also affects access to high-quality, timely care compared to white women.

The search for advances

In future years, we hope we will find specific mechanisms that explain the observed racial differences in breast cancer mortality. Eventually, we believe it will be possible to give each patient customized targeted treatments based on their genetic profile and other factors.

There are many factors that will need to be addressed to create racial equity in breast cancer outcomes. Bridging the gap will require a wide range of experts: clinicians, bioinformaticians, diagnosticians and epidemiologists from the science side, but also social scientists and public health experts. Only by joining together can we make sure that all breast cancer patients get the treatment that is best for them.![]()

Padmashree Rida, Research Scientist, Georgia State University and Ritu Aneja, Professor of Biology, Georgia State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.