Julie Dunne, University of Bristol

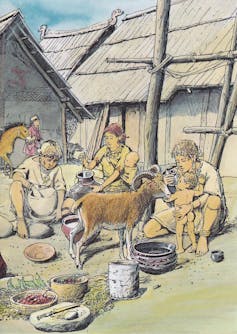

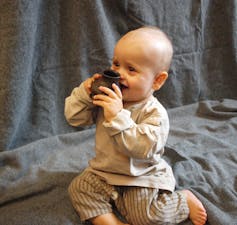

How did people look after their children in the Stone Age? It turns out that prehistoric parents may not have been so different to modern mums and dads. Clay vessels that have been found in Germany could have been used to supplement breast milk and wean children more than 5,000 years ago. They became more common across Bronze and Iron Age Europe and are thought to be some of the first-known baby bottles.

Analyses of child skeletons from this period suggest that supplementary foods were given to babies at around six months and weaning was complete by two to three years of age. These bottles are often stray finds on dig sites of ancient settlements and come in all sorts of shapes, but are always very small and have a spout through which liquid could be poured or suckled.

Sometimes they take the form of very cute mythical animals with feet and heads, perhaps made by the parents to entertain their children. Archaeologists have suggested that they were used to feed infants, but they might also have fed the sick or elderly. Until now, no one knew their true purpose, or what types of food they might have contained.

Parenting through the ages

In our study, we decided to investigate these objects using a technique called organic residue analysis. We found three in European child graves and two of them were complete. Normally we’d grind up broken pots, but we couldn’t possibly do this to these very small and precious vessels.

Instead, we did some very delicate drilling to produce enough ceramic powder and then treated it with a chemical technique that extracts molecules called lipids. These lipids come from the fats, oils and waxes of the natural world and are normally absorbed into the material of the prehistoric pots during cooking, or, in this case, through heating the milk.

Read more: What ancient footprints can tell us about what it was like to be a child in prehistoric times

Luckily, these lipids often survive for thousands of years. We regularly use this technique to find out what sort of food people cooked in their ancient pots. It seems they ate many of the things we eat today, including various types of meat, dairy products, fish, vegetables and honey.

Our results showed that the three vessels contained ruminant animal milk, either from cows, sheep or goat. Their presence in child graves suggests they were used to feed babies animal milk, as a supplementary food during weaning.

This is interesting because animal milk would only have become available as humans changed their lifestyles and settled in farming communities. It’s at that time – the dawn of agriculture – that people first domesticated cows, sheep, goats and pigs. This ultimately led to the “Neolithic demographic transition”, when the widespread use of animal milk to feed babies or as a supplementary weaning food in some parts of the world improved nutrition, contributing to an increased birth rate. The human population grew significantly as a result, and so did settlement sizes, which eventually became the towns and cities we know today. By holding these ancient baby bottles, we’re connected to the first generations of children who grew up in the transition from hunter-gatherer groups to communities based around agriculture.

This research gives us a greater insight into the lives of mothers and babies in the past and how prehistoric families were dealing with infant feeding and nutrition at what would have been a very risky time in an infant’s life. Child mortality would have been high – there were no antibiotics in those days – and feeding babies with animal milk would have come with its own set of risks. Although it may have provided a valuable source of nutrition, today we know that unpasteurised milk carries the risk of contamination from bacteria and can transmit disease from the animal.

Like all good research, this begs a range of new questions. Both the ancient Greeks and the Romans used very similar vessels and we know of a small number in a prehistoric site in Sudan. It would be interesting to see how these generations of children were fed and raised elsewhere in the world. It’s perhaps Comforting to know that despite the vast distance of time, these people loved and cared for their children in much the same way that we do today.![]()

Julie Dunne, Postdoctoral Researcher in Archaeology, University of Bristol

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.