Each year more than 24,000 Australians experience a sudden cardiac arrest. This means their heart unexpectedly stops beating. A cardiac arrest leads to loss of consciousness and will result in death if not recognised and treated immediately.

While survival rates vary depending on the exact cause of the cardiac arrest, the person’s age and other factors, survival invariably depends on early cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and defibrillation. Each minute of defibrillation delay significantly decreases the person’s chance of survival.

So in the instance of a cardiac arrest, in the time before emergency services arrive, help from members of the public can be critical in saving a person’s life.

Anyone can have a cardiac arrest

Many cases of cardiac arrest occur in older people due to underlying heart disease. But cardiac arrest can occur with little or no warning in people who were previously well, including children and young adults. This can be due to heart disease or cardiac rhythm disorders that may be undiagnosed.

Immediate treatment involves CPR. CPR is not the cure, but can save a person’s life by maintaining some blood flow to vital organs until the underlying cause of the cardiac arrest can be treated.

Most cases of cardiac arrest are a result of heart disease that can produce a sudden disruption to the heart’s normal rhythm. Resuscitation in these cases depends on the use of a defibrillator to deliver a calculated electrical current or “shock” through electrodes applied to the patient’s chest. This aims to return the heart to a normal rhythm, which is essential to restore blood flow from the heart.

Defibrillators in public places

A paramedic or other first responder has traditionally performed defibrillation. But there can be a delay from the time of the emergency call to the arrival of emergency service personnel, due to factors like the location of the incident and traffic conditions.

Public health initiatives to reduce the time to defibrillation have installed automated external defibrillators (AED) in public places. These devices are designed to be used by members of the public without prior training.

The number of AEDs in public spaces has increased significantly in the past few years. AEDs are now commonly found in workplaces and public spaces such as airports, casinos, sporting venues, and shopping centres. Both Woolworths and Coles have recently installed AEDs in stores across Australia.

Bystanders can save more lives

Research shows a marked improvement in survival from cardiac arrest in the past two decades. One study reviewed cases of cardiac arrest in adults attended by Ambulance Victoria from 2000 to 2017 to examine trends in the number of survivors.

This research found an eight-fold increase in patients shocked by bystanders where the cardiac arrest occurred in a public place, from 2.9% in 2000-2002 to 23.5% in 2015-2017. Compared to patients in cardiac arrest shocked by paramedics, those shocked in the first instance by bystanders had double the chance of surviving to hospital discharge (55.5% versus 28.8%).

These results are consistent with international research, which shows defibrillation by members of the public using AEDs is associated with significantly improved chances of survival.

Read more: How Australians Die: cause #1 – heart diseases and stroke

Mobilising trained volunteers

The Heart Foundation found 70% of adults would be willing to use an AED to help someone in an emergency. But only about one-third of respondents would feel confident doing so.

The need to reduce time to CPR as well as the need to quickly locate and operate AEDs in an emergency has led to the development of smartphone apps that enable members of the public to register as volunteer responders.

One of the most widely used apps in Australia and New Zealand is GoodSAM (Smartphone Activated Medics), which Ambulance Victoria has recently integrated with its emergency call-taking and dispatch system.

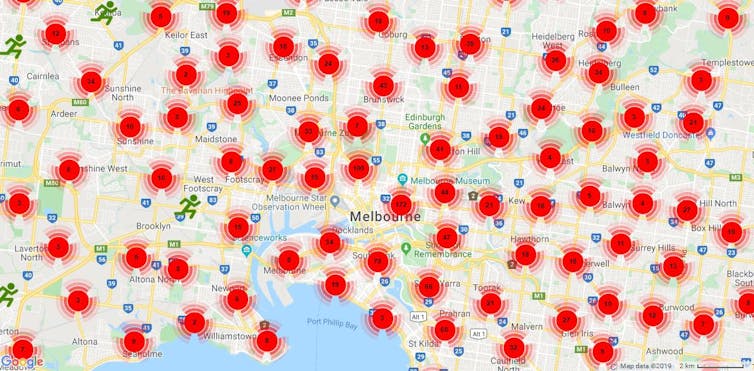

This app allows people with approved first aid or emergency health-care qualifications to register as a responder. Ambulance services that have integrated GoodSAM within their dispatch systems can alert a registered GoodSAM responder at the same time an ambulance is dispatched. So the responder receives the location of the suspected cardiac arrest – as well as the location of the nearest AED – often enabling care prior to the arrival of emergency services.

Ambulance Victoria and the Victorian government have been active in promoting GoodSAM, and the large number of responders currently available in Victoria makes this state one of the safest places in the world to have a cardiac arrest.

Both the South Australian Ambulance Service and NSW Ambulance Service are planning to follow Victoria and integrate the app into their operations. In order to save more lives, all state ambulance services should fully integrate GoodSAM with their ambulance dispatch systems.

And what can you do? Everyone who is able to should undertake first aid and CPR training. If you have the relevant training, I would urge you to sign up to GoodSAM. You never know when you may be able to save a life.

Read more: When is it OK to call an ambulance? ![]()

Bill Lord, Adjunct Associate Professor, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.