Andreas Hougaard Laustsen, Technical University of Denmark; Line Ledsgaard, Technical University of Denmark, and Timothy Patrick Jenkins, Technical University of Denmark

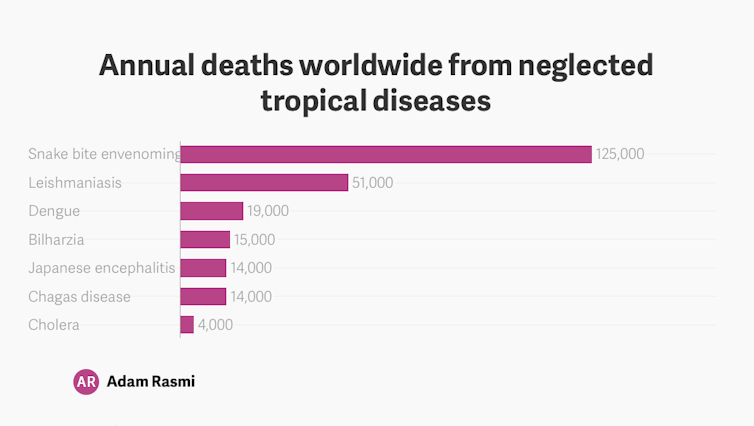

Amid global health crises such as coronavirus, snakebite envenoming is easily overlooked. The disease caused by the toxins that come from a snakebite is not infectious and it can’t spread rapidly and without warning. Nevertheless, it’s found around the world, affects millions of people, and can be life-threatening.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), more than 5.4 million people are bitten by snakes each year, resulting in 2.7 million envenomings, 400,000 permanent disfigurements and 150,000 deaths. The region most severely affected is sub-Saharan Africa, with more than 20,000 deaths annually.

The WHO added snakebite envenoming to its list of neglected tropical diseases in 2009, but removed it in 2013 without any explanation. In 2017 the organisation reinstated snakebite – not because the threat itself had changed but because of campaigning by antivenom producers, researchers, and health-care providers.

Returning it to the list opened the way for the WHO to set four strategic goals to deal with with this issue. These are:

- empowering communities;

- ensuring safe and effective treatments;

- strengthening health systems; and,

- increasing partnerships, coordination and resources.

The goals support a target of halving the deaths and disability from snakebite by 2030.

Empowering communities

The first goal requires research to understand what influences the behaviour of people at risk and what would encourage people to seek treatment for snakebite?

In sub-Saharan Africa, disease caused by snakebite is often treated by traditional healers rather than medical doctors in hospitals. Some of the treatments don’t do harm but still delay the patient from getting to a hospital. But the traditional healers who administer these treatments are often highly revered and respected. So, any medical advice offered to communities must show cultural sensitivity and respect.

The WHO suggests using local champions to lead efforts to introduce “first aid” and help get patients medical help quickly and safely.

Making antivenoms accessible and affordable is also key, since people need to pay for them out-of-pocket in most African countries. The current cost of antivenoms presents a huge issue even when they are available. This problem is amplified by the fact that the people most at risk from snakebite are also the most impoverished populations in sub-Saharan Africa.

Read more: Snakebites still exact a high toll in Africa. A shortage of antivenoms is to blame

Safe and effective treatment

Most antivenoms consist of sheep or horse antibodies and they have been made in much the same way since they were invented 120 years ago. Consequently, the quality and safety of some antivenoms remain poor and production remains costly.

The WHO is pushing towards creating a stable and sustainable market for safe and effective antivenoms at reasonable cost. Producing treatments that meet internationally accepted standards will require cooperation between researchers, industry, and other institutions.

The plan to improve supply involves creating a revolving stockpile of effective antivenoms, so they can be distributed to the regions most in need. More specifically, the WHO aims to deliver at least 500,000 effective antivenom treatments to sub-Saharan Africa each year by 2024 and 3 million by 2030.

Stronger systems

The third goal is to improve aspects of health systems like pre-hospital care, transport, diagnosis, rehabilitation and recovery support. The benefits of doing this have already been seen in Myanmar and Nepal.

Finally, all the efforts towards these goals will require partnerships, coordination, and resources at a global scale. They will also make a difference to other diseases found in tropical areas. For example, promoting footwear to prevent snakebite will also help prevent soil-associated diseases such as hookworm or podoconiosis. The use of bed nets to prevent nocturnal snakebites will also help prevent malaria. Better wound care will also benefit patients with Buruli ulcer.

The WHO will scale up its work on snakebite from 2021 to 2024, in 45 to 52 countries. The final rollout will be from 2025 to 2030 and many of the early measures will be tested in African countries.

Notably, such early efforts have already made an impact. Since snakebite envenoming was put on the WHO’s list of neglected tropical diseases again, media attention has improved and research funding has been mobilised. In fact, snakebite was on the World Health Assembly’s agenda for the first time in 2018.

Together, these developments suggest that the goal of reducing snakebite mortality and morbidity by 50% by 2030 might be achievable. At the very least there is hope for people in sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere that they will get better support from the global health community. Snakebite will hopefully not remain neglected for long.![]()

Andreas Hougaard Laustsen, Associate Professor at the Department of Biotechnology and Biomedicine, Technical University of Denmark; Line Ledsgaard, PhD Candidate, Department of Biotechnology and Biomedicine, Technical University of Denmark, and Timothy Patrick Jenkins, Post Doctoral Researcher, Technical University of Denmark

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.