Michael S. Kobor, University of British Columbia; Candice Odgers, University of California, Irvine; Kim Schmidt, University of British Columbia, and Ruanne Vent-Schmidt, University of British Columbia

One fortunate aspect of COVID-19 is that children have been less directly affected by the disease. But despite the relatively low incidence of severe illness in children, the response to the pandemic may have long-term adverse effects on the health and well-being of children and adolescents.

As researchers in psychology, genetics and developmental biology in the Social Exposome Research Cluster at University of British Columbia and the Child and Brain Development Program of CIFAR, we investigate the biological mechanisms by which social factors get “under the skin” to influence child health and development. We are concerned because some of the unintended consequences of the public health response to the pandemic are increased stressors for children and adolescents.

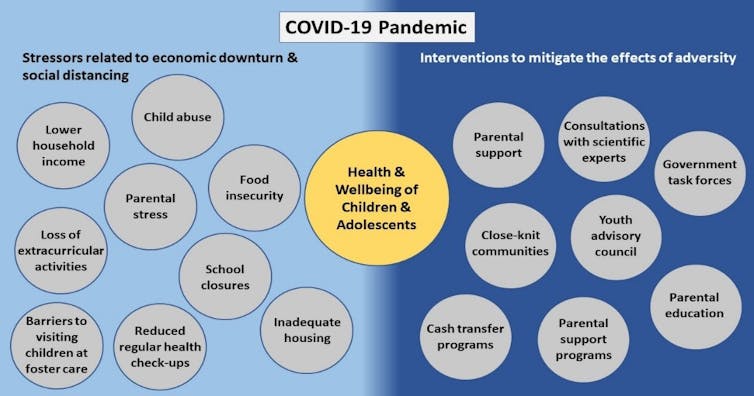

These stressors — reduced family income, food insecurity, parental stress and child abuse — can become biologically embedded and negatively impact children’s developing brains, immune systems and ability to thrive. While some effects will be immediate, many will surface decades from now.

Stressors can leave lasting imprint on health

For the more than 500,000 Canadian children under the age of 18 living in poverty (and one in four children in single-parent households) prior to the pandemic, the shocks have been great. As of June, the unemployment rate in Canada reached a record high of 13.7 per cent, with cumulative employment losses over three million since February. This is especially worrisome. One striking example shows that financial hardship in early life is related to higher risk of metabolic syndrome and physical health problems in adulthood, often independent of adult income and resources. The concern now is the extent to which these massive shocks will impact children’s lifelong health and well-being.

Read more: New DNA test that reveals a child’s true age has promise, but ethical pitfalls

Children and adolescents are facing these stressors without access to the stabilizing routines and activities that typically support their development. Most of Canada’s schools are closed or only open part-time. With the summer ahead, cancellations and restrictions of young people’s sports and summer camps means further loss of opportunities for learning, social interaction and play. For adolescents, who need peer interaction to support development, social deprivation and reduced opportunities for social learning are likely to have far-reaching consequences on their development and mental health.

Biological pathways

Stressors stemming from the pandemic may become biologically imprinted in children and leave a lasting mark on child and adult health and well-being. There are several biological pathways that can be modulated by early life experiences, but epigenetics — a process that turns genes “on” or “off” — is particularly well-studied. Epigenetic changes associated with early experiences can last into adulthood and may be linked to stress, inflammation and chronic heath conditions.

While scientists continue to map the exact mechanisms by which early experiences impact adult health, what is clear is that children who experience adversity early in life are at heightened risk for later mental, social and physical health problems. Additional protections for children and families are needed to prevent the negative effects of COVID-19 from following children, especially those already at greatest risk, into adulthood.

Canada is not alone in failing to prioritize the basic needs of children and adolescents in reopening plans. In the United Kingdom, an open letter to the prime minister was signed by 1,500 pediatricians on June 17 citing the risks of “scarring the life chances of a generation of youth” due to the prolonged closure of schools. This letter urged the government to prioritize the opening of schools to prevent widening inequalities, disruption of learning and the inability to deliver essential supports for children, including mental health supports, therapies, school meals and early years services.

Creative and safe plans are required for reopening schools and allowing safe social interactions. These measures will benefit all young people, but a specific focus is needed to support young people most affected by the amplification of social inequalities. In particular, as we emerge from this crisis, more support is required for those who may have experienced child abuse and domestic violence.

Helping children and adolescents thrive

It’s not too late to prevent children and adolescents growing up in the pandemic from becoming unintended casualties. We are facing the possibility of seismic shifts in population health and well-being if we do not act. The good news is that there are specific and evidence-based actions we can take.

The presence of warm and supportive adults can protect children from stressful life events. Close bonds between parents and children are protective against the harmful, long-term effects of financial insecurity on the immune system — extending into adulthood. Grandparents, teachers, coaches, other important adults and close-knit communities in the lives of children are offering inspiring examples of how to creatively connect and support children digitally and in physically, but not socially, distanced ways.

Creating opportunities for children and adolescents to be involved in the rebuilding plan can empower young people as leaders. A diverse youth advisory council, such as the Mental Health Commission of Canada’s Youth Council, can advocate by incorporating the wisdom and vision of young people’s lived experiences.

We urge policy-makers to seek scientific evidence and consult with experts focused on child development, including pediatricians, psychologists and researchers in the biology of early life experiences. To start, policy-makers should invest in solutions to minimize the evidence-based Top 10 Threats outlined by Children First Canada. These include depression, anxiety and child abuse — all of which are amplified by the pandemic. Finally, we urge the creation of diverse federal and provincial pandemic recovery task forces to create an evidenced-based strategy for supporting children and adolescents.

Institutions, educators and leading scientists also have a role to play in advocating for young people who do not vote, and as a result often do not have a voice in policy discussions. The late Dr. Clyde Hertzman, founding director of the Human Early Learning Partnership, was a tireless advocate for increasing investments in child health and education to prevent adversity in childhood from evolving into disease. His life motto of “it doesn’t have to be this way” has never been more relevant.

Now is the time to work quickly and collectively to ensure that this pandemic does not leave its imprint deep in the biology of the next generation.![]()

Michael S. Kobor, Canada Research Chair in Social Epigenetics and Professor, UBC Department of Medical Genetics, University of British Columbia; Candice Odgers, Professor of Psychological Science, University of California, Irvine; Kim Schmidt, Research Manager, Healthy Starts Theme, BC Children's Hospital Research Institute; Steering Committee Member, Social Exposome Research Cluster, University of British Columbia, and Ruanne Vent-Schmidt, Research Manager, Social Exposome Research Cluster, University of British Columbia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.