Emily Jenkins, University of British Columbia; Anne Gadermann, University of British Columbia, and Corey McAuliffe, University of British Columbia

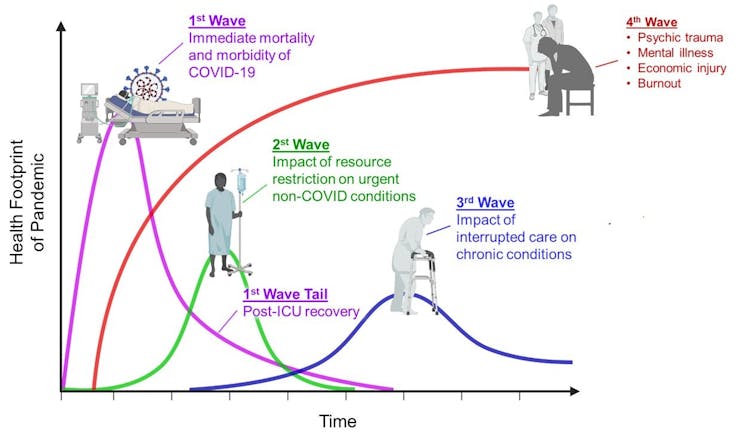

The mental health consequences of COVID-19 can be described as the “fourth wave” of the pandemic, and are projected to result in the greatest and most enduring health footprint.

Canadian data show growing mental health concerns across the country. In April 2020, the Angus Reid Institute found that 50 per cent of Canadians felt their mental health had worsened during the pandemic, indicating high levels of worry and anxiety. The following month, Statistics Canada reported only 54 per cent of Canadians identified their mental health as “very good” or “excellent” in 2020, compared to 68 per cent two years earlier.

As mental health researchers working in collaboration with groups who have long experienced health and social inequities, we know that general population data do not tell the whole story. The toll of the pandemic is not distributed equally.

Root causes and differential mental health impact

Growing mental health challenges amid the pandemic illustrate how profoundly population-level mental health is shaped by the social determinants of health — the everyday conditions in which we live. Increases in mental health challenges have been attributed to months of physical distancing, growing job loss, economic uncertainty, housing and food insecurity and child care or school closures. Many of us are attempting to balance far too much, and it is taking a toll.

Our research, done in partnership with the Canadian Mental Health Association, adds new and concerning nuances to these trends.

During the first phase of the economic reopening in May, we conducted a nationally representative survey of 3,000 adults over 18 years old in Canada. Thirty-eight per cent of the general population reported experiencing a deterioration in mental health since the onset of the pandemic. This effect was more pronounced in specific groups: 59 per cent of those with a pre-existing mental health condition reported this experience, 48 per cent of those with a disability, and 44 per cent of people living in poverty.

A rise in suicidal thoughts

Our research also shows a significant jump in suicidal thoughts or feelings arising from the pandemic, with six per cent of the general population reporting this compared to 2.5 per cent in 2016.

Again, the impact is greater on groups marginalized by social circumstances and stigma, with 18 per cent of those who reported a pre-existing mental health condition identifying suicidal thoughts/feelings — nearly one in five people. Sixteen per cent of those who identified as Indigenous reported experiencing suicidal thoughts, as well as 14 per cent of people with a disability and 14 per cent of those identifying as LGBTQ+. This sobering finding has been linked to extraordinarily high rates of unemployment and economic instability and aligns with respondents’ greatest sources of stress: financial concerns, including job insecurity.

Our study further identified food insecurity as a considerable concern and potential challenge to mental health. Specifically, 18 per cent worried about having enough food for their family. This concern was magnified to affect 37 per cent of those living in poverty, 28 per cent of those with a disability, 26 per cent of racialized people and 25 per cent of Indigenous people. The relationship between food insecurity and mental challenges is well established.

Additionally, our study identified that fear of domestic violence was high, with nine per cent of respondents reporting this concern. This was twice as likely (18 per cent) among racialized people and also high (14 per cent) among Indigenous people. This consequence has been described as a “shadow pandemic,” with implications for persistent adverse mental health outcomes, particularly for women.

Equity must be part of the equation

Our research confirms that the toll of the pandemic is not distributed equally and is among the first to show that those who are systematically oppressed due to their mental health or disability status, income, ethnicity, sexuality or gender have borne the brunt of the pandemic’s mental health consequences. This will continue unless we frame our public health and policy responses towards equity.

We need an overhaul in our approach to mental health.

When last estimated, costs associated with mental health challenges in Canada topped $51 billion annually. As well, our mental health system is insufficient in addressing demand and not equipped to respond to the everyday conditions responsible for many mental health challenges, particularly as they relate to the pandemic.

We need a comprehensive and equity-oriented mental health strategy that not only includes prevention and treatment, but also promotion.

Mental health promotion is a strengths-based approach that emphasizes healthy public policy. Characterized by “explicit concern for health and equity in all areas of policy,” it enhances community and population-level mental health responses, especially for those experiencing the greatest risk.

Read more: How to build a better Canada after COVID-19: Transform CERB into a basic annual income program

In the case of COVID-19, this includes poverty reduction strategies, such as universal basic income, to mitigate the effects of job loss and economic hardship to prevent suicide and further mental health decline.

Also important are trauma- and violence-informed mental health supports, developed in collaboration with communities that will access them. It includes dedicated efforts to safely reopen schools and childcare centres, delivering programming to support children’s social-emotional development, and often providing safety, food security and mental health supports as well as respite for struggling parents.

Now more than ever, public health and mental health strategies need to align to address the impact of the pandemic. An equity-oriented response is the only solution for a sustainable recovery.![]()

Emily Jenkins, Professor of Nursing, University of British Columbia; Anne Gadermann, Assistant Professor, School of Population and Public Health, University of British Columbia, and Corey McAuliffe, Postdoctoral Fellow, School of Nursing, University of British Columbia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.