Jane E. McArthur, University of Windsor

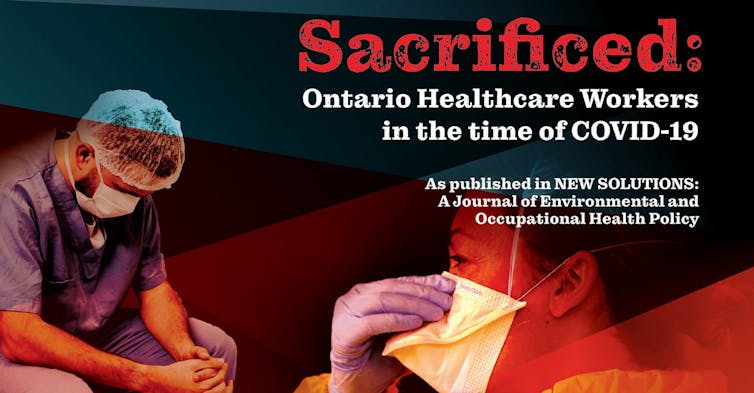

Health-care workers in Ontario — a workforce that is predominantly women, many of whom are racialized — have been made especially vulnerable during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The risk of being infected with COVID-19, the lack of preparedness by governments, little success in arguing for better protection and being barred from speaking publicly have left health-care workers feeling angry, fearful and sacrificed. The vulnerability and physical and mental health impact on health-care workers also affects health-care delivery to the public.

The COVID-19 pandemic changed the landscape of the health-care system. Health-care workers have been disproportionately infected, making up nearly 20 per cent of cases, higher than the global rate among health-care workers. Meanwhile, worldwide shortages of N95 masks influence local protection guidelines.

After the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003, an independent commission provided a roadmap for handling future pandemics. Recommendations included that N95 masks be available to health-care workers at all times. But governments disposed of expired N95s and other medical supplies and failed to replace them.

Health-care workers in need of protection from COVID-19 and other risky working conditions in their jobs confidentially reported the impact of these decisions in our recent study. The research, a collaboration between University of Windsor occupational health researchers and the Ontario Council of Hospital Unions (OCHU-CUPE), which funded the study, unveils the stories behind the statistics of the thousands of health-care workers who have been infected with COVID-19.

Study gives voice to health-care workers

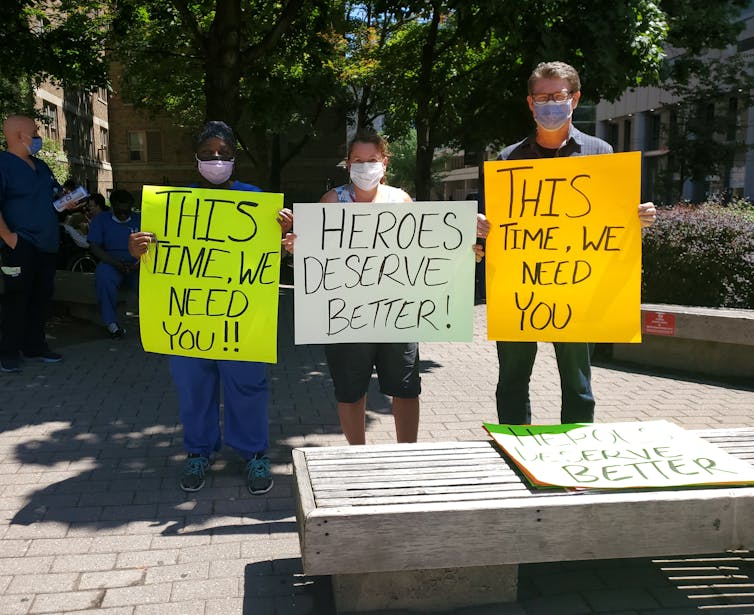

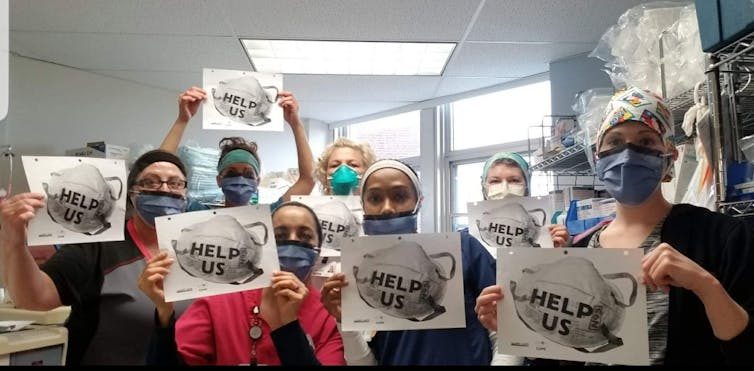

Health-care workers are not allowed to talk publicly about their working conditions. They are systematically silenced — disciplined or fired — for speaking out about unsafe working conditions.

We conducted anonymous telephone interviews in April and May 2020 with 10 health-care workers recruited with the assistance of the OCHU-CUPE provincial office. Another five participants cancelled, with two specifically citing fear of discipline or job loss if identified.

Prevalent themes in interviews included psychological distress, inadequacy of protection, inconsistencies in policy, government failings and barriers to agency. The stress and anxiety experienced by health-care workers were most prominent.

During study recruitment, potential interviewees said they were too afraid to participate for fear of losing their jobs. A hospital clerical staff person interviewed for the study said,

All the front-line workers fear reprisal. We are told, “You can’t talk to the media."… It’s just such a travesty and these issues need to be said and people need to know what’s really going on.

The study safely and anonymously gives health-care workers a public voice and provides insight into their working conditions.

Health-care workers share society’s background mental distress as well as stressors related to their work. An authoritarian and hierarchical culture in health-care work is described by health-care workers as contributing to risk and adverse mental health effects.

Interviewees reported that the risk of contracting COVID-19 and infecting family members or patients created intense anxiety. With under-staffing and increased workloads as well, health-care workers are suffering from exhaustion and burnout.

There’s a lot of anxiety. When COVID-19 is over, the employer won’t have enough counsellors on hand to handle what I think is going to hit. Because people are anxious; people are fearful. They come to work; they don’t know if they have the illness or not, because sometimes you’re asymptomatic. They’re afraid to go home; their families are scared of them. It is just horrendous. And the morale is as low as it can be.

A personal support worker (PSW) in a long-term care facility described difficulty coping with added stress, increased workload and making the sacrifice of working longer hours to keep up care:

There’s definitely extra stress, and some days, you just break down and start crying.… Our workload is crazy, and the girls are just running on the floor to keep up.… Before the pandemic, we had a shortage of PSWs, and now we have more and more people going off work because they’re afraid. A lot of the staff are working double shifts.

Government failures create risks for health-care workers

Ontario’s health-care system has been eroded by economic strains, understaffing and diminished capacity. Interviewees divulged regulatory inadequacies. Health-care workers are at risk of COVID-19 exposure, yet left without adequate protections — including personal protective equipment (PPE) and administrative and engineering controls — as well as a lack of adherence to the precautionary principle, as explicitly recommended in the SARS Commission Report.

The controversy around the aerosol transmission of SARS-CoV-2 affected health-care workers’ safety. N95 masks, considered the best protection against virus transmission, have not been available to health-care workers as authorities debated the science that established airborne transmission. Several health-care workers said requests for N95s were ignored. Supervisors warned nurses, saying:

You are not to wear an N95 mask; you do not need it, you are fine to be wearing the mask with a shield, and if I catch you with one on again, you can be fined.

Another nurse, told she couldn’t wear her own N95, resorted to hiding one she had purchased herself under a medical mask.

There is little trust in government decisions and policies for protection. A long-term care PSW explained:

It makes it difficult when we feel that the best decisions for our safety — especially in regard to PPE — are not truly the best practice.… That’s a big concern for us on the front line.

Another health-care worker interviewed put it very simply:

All we are asking is, please protect us!

Protecting health-care workers and the public

Our study uncovers implications for health-care workers and health-care provision, and concludes with recommendations that include:

Increased staffing levels in Ontario’s hospitals and in long-term care.

Changes to the workplace culture so health-care workers are heard.

Strong management support to mitigate mental distress.

Improved working conditions and PPE.

Legislated protection to allow staff to speak without reprisal.

This article was co-authored by James T. Brophy, University of Windsor, University of Stirling, Athabasca University; Margaret M. Keith, University of Windsor, University of Stirling; and Michael Hurley, president OCHU-CUPE.

Jane E. McArthur, Doctoral Candidate, Sociology-Social Justice, University of Windsor

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.