Ñusta Carranza Ko, University of Baltimore

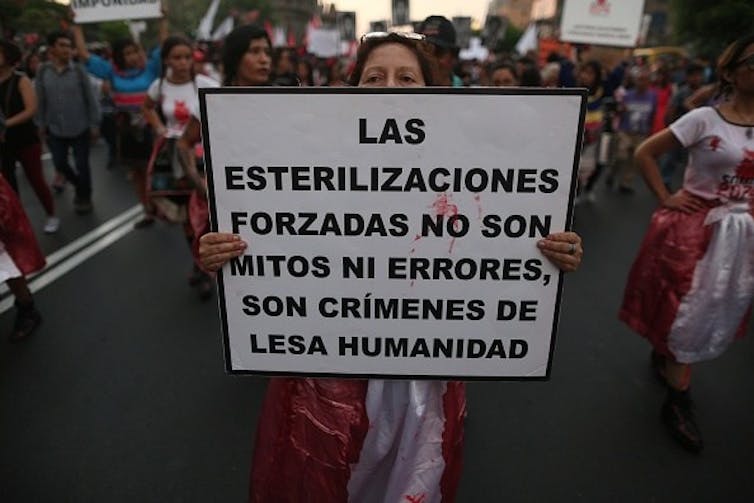

The regime of Peruvian dictator Alberto Fujimori sterilized 272,028 people between 1996 and 2001, the majority of them Indigenous women from poor, rural areas – and some without consent.

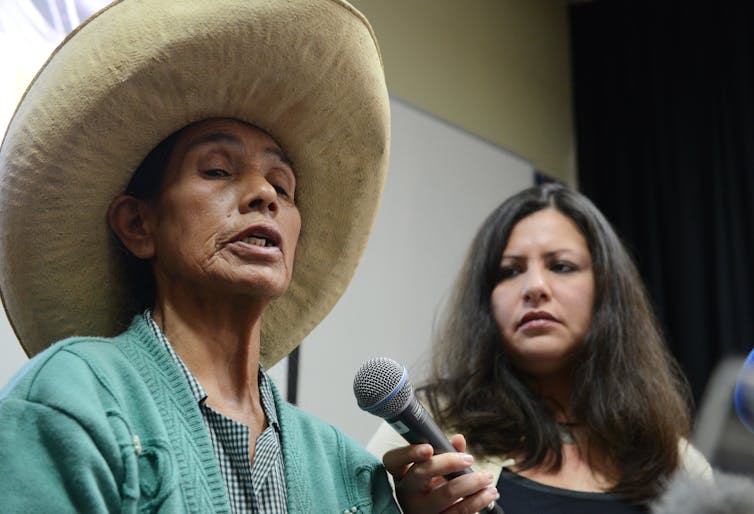

Now, in public hearings that began earlier this year, thousands of these women are demanding justice for what they say were forced sterilization procedures called tubal ligations.

Sterilization was a covert part of Fujimori’s “family planning” policy, which purported to give women “the tools necessary [for them] to make decisions about their lives.” But in fact, as revealed in government documents published by the Peru human rights ombudsman’s office in 2002, the regime saw controlling birth rates as a way to fight “resource depletion” and “economic downturn.”

These were euphemisms for what Fujimori, and past leaders of Peru, referred to as the “Indian problem” – higher birth rates among Indigenous people than Peruvians of European descent. And since Indigenous women of Quechua descent had the highest poverty rates in Peru, they were the government’s main target for “family planning.”

Rather than getting consultations on their reproductive rights, as other Peruvian women did when they visited public health clinics, Indigenous women were offered “family planning” methods, one of which was tubal ligation.

“Health officials took me to the hospital … and forced me to undergo surgery,” testified Dionicia Calderón in a public testimony organized by the National Organization of Andean and Amazonian Indigenous Women in Peru in 2017.

Indigenous Peruvians are widely recognized as particular victims of the Fujimori dictatorship. But my research documenting Indigenous women’s stories finds that the crime of forced sterilization has been underplayed in Peru’s post-Fujimori reckoning with the past.

Truth and justice

Victims and families of victims of forced sterilization began to seek legal recourse in 1998, two years before Fujimori’s downfall.

The family of María Mamérita Mestanza – who was coercively sterilized, suffered health complications and died on April 5, 1998 – filed charges with the national prosecutor’s office against the chief of the health center that performed her tubal ligation. But judges twice ruled that there were insufficient grounds to prosecute the doctor.

In 2004, official investigations by prosecutors began against Fujimori into his regime’s “compulsive application of sterilizations.” But after Fujimori was prosecuted and convicted by Peru’s Supreme Court for other human rights abuses, the sterilizations case was closed because it was not considered genocide or torture, and the crimes could not be charged within Peru’s existing penal code.

Investigations were reopened in 2011 after the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, an international legal body, pressured the state to investigate the case, citing the high number of victims. By January 2014, Peru’s Public Ministry was pursuing charges against doctors for María Mamérita Mestanza’s death. But it re-closed 2,000 other cases, saying there was insufficient evidence to hold Fujimori himself accountable.

For years, the roughly 2,000 forced sterilization cases continued to bounce around the Peruvian criminal justice system. Every so often, authorities would open investigations into some low-level officials accused of participating in the “family planning” program, only to close them again because of “insufficient information.” This was part of general impunity surrounding Fujimori, whose son and daughter are both politicians.

Meanwhile, Indigenous groups were recording the testimonies of these women and creating an online archive in which Indigenous women recall their forced sterilization. Called “Quipu,” the database – along with pressure from international human rights groups like Amnesty International – helped pressure the government to holding public hearings on the topic.

In January of this year, the first official government hearings on coercive sterilizations began in Lima. But they were suspended after just one day, when Judge Rafael Martín Martínez determined the court needed more translators for the wide variety of Quechua dialects spoken by the victims.

Hearings resumed on March 1 in Lima, to “formalize the charges for mediated authorship on the crimes against life, body, and health; grievous bodily harm causing death,” according to prosecutor Pablo Espinoza Vázquez.

In addition to wrenching testimonies from victims, the prosecution presented damning evidence that Fujimori and his health ministers set an annual sterilization quota. For instance, in 1997, Fujimori’s government aimed to sterilize 150,000 people, the prosecutor alleged, regardless of their health condition or consent.

The majority of the victims of coercive sterilizations were of Indigenous descent.

Difficult road ahead

The hearings have given thousands of Indigenous women in Peru hope that their abusers may finally be held criminally accountable for violating their reproductive rights, depriving them of children and decimating the Indigenous population by preventing the births of future generations.

And recent legislative changes now entitle victims of forced sterilizations to medical, financial and educational reparations, and potentially an official apology.

But former president Fujimori and his inner circle retain links with powerful people in politics. Despite efforts to punish them for the crimes of the dictatorship, they have largely escaped justice.

Fujimori was convicted in 2009 and jailed for crimes against humanity, but his conviction was overturned in 2017 on health-related grounds. This so-called “humanitarian” pardon was annulled in 2017, and in 2018 a court-appointed team of medical experts concluded the former dictator was fit to serve the rest of his sentence. Fujimori was ordered back to jail.

His daughter, Keiko Fujimori, a candidate in this year’s Peruvian presidential election, says she would consider pardoning her father if she won.

So the road to actually convicting Fujimori for reproductive violence against Indigenous women is long. His victims, telling their stories publicly now, know how often their cases were previously dismissed due to “insufficient information” and how marginalized their voices have been in Peru’s transitional justice process.

Despite the odds, victims and their families maintain hope that this time things will be different. As the daughters of two women who died of coercive sterilization-related medical complications declared, “Without judicial investigations, there is no truth, and without truth, there will be no justice.”

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Ñusta Carranza Ko, Assistant Professor, School of Public and International Affairs, University of Baltimore

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.