Stefanie Malan-Muller, Stellenbosch University

South Africa is one of 10 countries globally where more than 70% of the population has suffered from a traumatic event in their lifetime. These traumatic events contribute to the high rates of anxiety and stress related disorders.

Of the South Africans who experience trauma, about 3.5% – about 1.4 million people – will eventually develop posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

PTSD is a debilitating psychiatric disorder that can develop after a traumatic experience. Most people recover naturally, but some experience symptoms, like flashbacks, and severe stress and anxiety even when they are not in danger. This interferes with their daily functioning.

There are several factors that influence whether or not people are more likely to develop PTSD. This includes genetics, epigenetics (factors that influence the way genes are expressed into proteins) and the environments that they are exposed to.

Newer evidence is showing there may be another factor at play. Studies show that people who suffer from psychiatric disorders have high levels of inflammation in their bodies. Scientists are still unsure of how this inflammation comes about although some studies on animals have suggested the gut microbiome could play a role. They found that exposure to stress changed the gut microbiome of these animals and also resulted in increased levels of immune molecules and inflammation.

We therefore wanted to determine whether there were differences in the gut microbiomes of people who had developed PTSD, and those who hadn’t.

We found that people with the disorder have a deficit of a specific bacterial combination that regulates the immune system and inflammation. Currently we can’t say whether the disorder causes the bacterial deficit or if the bacterial deficit contributes to PTSD symptoms.

But our findings bring us one step closer to understanding how the gut microbiome plays a role in the disorder. It provides new ideas for future studies to determine whether these bacteria contribute to the disorder or whether they develop as a consequence. It could also help future studies to develop new treatments for PTSD.

A connection to the brain

In the last 10 to 15 years scientists have discovered a vast number of functions performed by the trillions of bacteria living inside the human gut (called the gut microbiome). These include the metabolism of food and medicine and protection against infections. But the gut microbiome also plays an important role in brain functioning and behaviour.

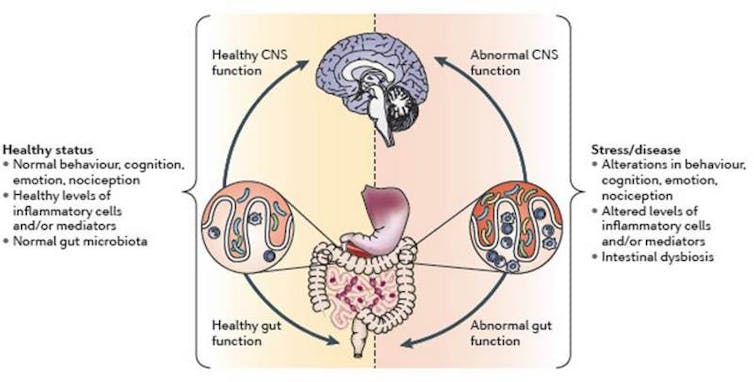

There is a complex interaction between the brain, the gut and gut microbiome called the gut-microbiome-brain axis. The microbiome can influence brain functioning and behaviour through several mechanisms. It communicates with the enteric nervous system – a complex system of millions of nerves in the lining of the gut. It also produces hormones, immune molecules and toxins which affect the brain.

Within this axis the interaction between the brain and the gut microbiome is bi-directional. This means that stress and emotions can also affect the gut microbiome. Hormones released during stress can affect the gut microbiome and the integrity of the intestinal lining, which, when compromised, enables bacteria and toxins to cross into the blood circulation. This leads to increased inflammation.

This gut-brain connection, as well as the high levels of inflammation seen in people with PTSD, led us to our hypothesis that the gut microbiome may be different in people diagnosed with the disorder.

A comparative exercise

Working with researchers from the University of Colorado Boulder in the US, we compared the gut microbiomes of people who suffered from PTSD with those who experienced a traumatic event, but didn’t develop the disorder.

When we looked at the composition of the gut microbiome of PTSD patients, we found they had very low levels of a combination of three bacteria: Actinobacteria, Lentisphaerae, and Verrucomicrobia, compared to the controls .

Previous studies have shown that these bacteria play an important role in regulating inflammation and the immune system. In turn, high levels of inflammation and changes in immune functioning can influence the brain, its functioning and behaviour.

We believe that the low levels of this trio of bacteria in PTSD patients may have contributed to a deficient immune system and heightened inflammation, which may have contributed to symptoms of PTSD.

It is, however, still unclear when these changes in the microbiome might have taken place. They may have occurred early in life as a response to childhood trauma. People who suffer high levels of childhood trauma have a higher risk of developing anxiety and stress related disorders later.

This correlates with another finding in our study, where people who experienced high levels of trauma during childhood had significantly lower levels of two of the earlier mentioned bacteria (Actinobacteria and Verrucomicrobia) compared to people with no or minimal childhood trauma.

The missing link, which needs to be validated in a larger, longitudinal sample, is whether differences in the bacterial composition are a cause or a consequence of PTSD.

Next steps

Our next steps are to repeat the study in a larger group, to include healthy controls, and to measure markers of inflammation and bacteria that crossed into the bloodstream.

We are also launching a large-scale, population based initiative to understand the connections between the gut microbiome and the brain. The South African Microbiome Initiative in Neuroscience will focus on people who have experienced trauma and been diagnosed with a mental or psychiatric disorder. This study will identify more links between the gut microbiome and disorders that affect the brain.

Understanding how the bacteria in the gut affects the brain and behaviour is the first step in establishing how different factors influence susceptibility and resilience to PTSD.

This could, in future, expand our knowledge and help scientists identify new treatment options for PTSD.

This is especially important since the microbiome can easily be altered with the use of prebiotics (non-digestible foods that bacteria digests), probiotics (live, beneficial bacteria) and synbiotics (combination of probiotics and prebiotics) or dietary interventions.![]()

Stefanie Malan-Muller, Postdoctoral fellow in Department of Psychiatry in the field of Psychiatric Genetics, Stellenbosch University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.