Mark Lorch, University of Hull

Many of us are familiar with the typical results of burning fuels such as coal, natural gas and oil. The reaction produces heat which we harness to warm our homes, heat water and cook food, power vehicles and generate electricity.

Combustion also produces gases, most obviously carbon dioxide. This is produced when the carbon, locked away in the petrol, gas or wood, reacts with oxygen in the air. We can’t see or smell carbon dioxide – it’s non-toxic and is unreactive – so most of the time as it drifts away into the air around us and we don’t give it a moment’s thought.

But carbon dioxide isn’t the only gas that results from burning of fuels. Carbon monoxide can also be produced. This too is invisible, tasteless and odourless. Unlike its chemical cousin, though, carbon monoxide is extremely poisonous.

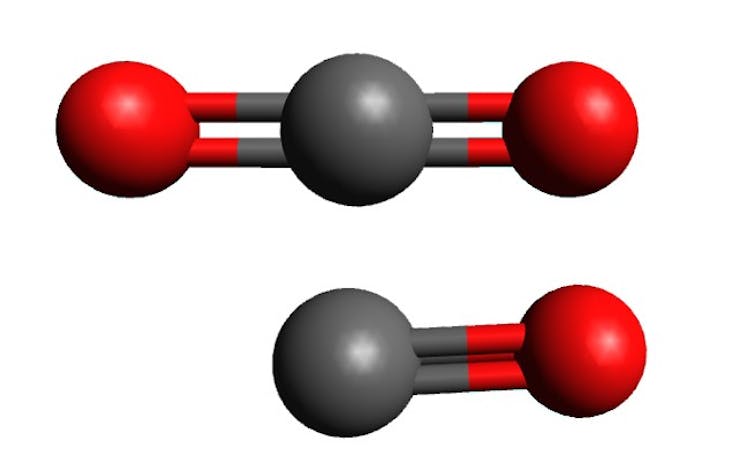

The difference between the two gases is small but very significant.

Carbon dioxide has a central carbon atom flanked by two oxygens, hence the “di” (meaning two) in the name, and the chemical formula CO₂. It is a very stable molecule because the carbon atom has fully reacted with the oxygens, leaving it with no potential to form bonds with anything else.

Carbon monoxide consists of a carbon and a single oxygen (hence the “mono” in the name and the formula CO). As a result the carbon is still able to react with other molecules. This reactivity is the root of its poisonous nature.

Carbon monoxide poisoning

Carbon monoxide poisoning results from the way it interacts with proteins that carry oxygen around your body. Normally haemoglobin in your blood binds oxygen as it passes through your lungs and then releases it where it is needed in the various organs of your body. Carbon monoxide also binds to haemoglobin, and it sticks over 200 times stronger than oxygen. This means it blocks the haemoglobin’s ability to bind oxygen and limits the body’s ability to move oxygen around the body.

The early symptoms of carbon monoxide poisoning include headaches or dizziness, breathlessness, nausea, tiredness, chest and stomach pains and visual problems. These are quite general and are easily confused with viral infections, food poisoning or just being tired. So low level poisoning is often overlooked. Higher doses result in loss of consciousness, long term heart and brain damage and death.

So how can we avoid being poisoned by this gas? Carbon monoxide is produced at high levels when fuels aren’t burnt correctly. This frequently occurs when wood, coal and charcoal fires are left to smoulder, or petrol, gas and kerosene appliances (such as boilers and space heaters) are not maintained properly. This is especially dangerous if generators, charcoal burners or barbecues are used in confined and poorly ventilated spaces such as tents and bars which allow CO to build up in the space with deadly consequences.

Early media reports suggest that carbon monoxide caused the deaths of 21 young people at a tavern (club) in South Africa’s Eastern Cape province in June. However, officials are still investigating and are yet to confirm the cause of these tragic deaths.

Keeping safe

Carbon monoxide poisoning is deadly, but it can also be easily avoided.

Maintenance: Make sure your vehicles, boilers, chimneys, generators and space heaters are inspected and maintained by a qualified technician at least once a year. During the rest of the year, check that gas flames are blue and not yellow or orange. And look out for soot around appliances and pilot lights that go out frequently.

Ventilation: Never use camp stoves, barbecues or charcoal heaters indoors or in tents. Only ever use petrol and diesel generators outdoors and well away from open windows and doors. Never use gas space heaters while you are sleeping, and only ever use them in well ventilated spaces. Never leave a vehicle running in a garage.

Monitoring: Buy carbon monoxide monitors and install them near boilers, fireplaces and anywhere where you might use an indoor space heater.

Seek treatment: If you think you or anyone near you is suffering from carbon monoxide poisoning then seek medical treatment.![]()

Mark Lorch, Professor of Science Communication and Chemistry, University of Hull

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.