Michelle Maroto, University of Alberta and Lisa Young, University of Calgary

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic.

The weeks that followed were filled with fear and uncertainty for many as governments began to implement protections that included school and daycare closures, work-from-home orders and other social distancing measures. These days seem both recent and far in the past.

In Alberta, a lot has changed since March 2020 and a lot has remained the same. Conducting five waves of the Viewpoint Alberta Survey puts us in a special position to gauge Albertans’ experiences and perspectives over the course of the pandemic.

By limiting the spread of the virus, government measures to contain the virus saved countless lives. Even still, since that date, there have been more than half a million recorded COVID-19 cases in Alberta, more than 34,000 hospitalizations and at least 5,500 deaths from the virus.

Today, many Albertans also live with the continuing consequences of long COVID, burnout and a health-care system pushed to the brink.

Drawing on surveys from August 2020, March 2021, September 2021, April 2022 and January 2023 shows how views on restrictions evolved, attitudes have changed and economic situations have diverged.

Pandemic’s toll

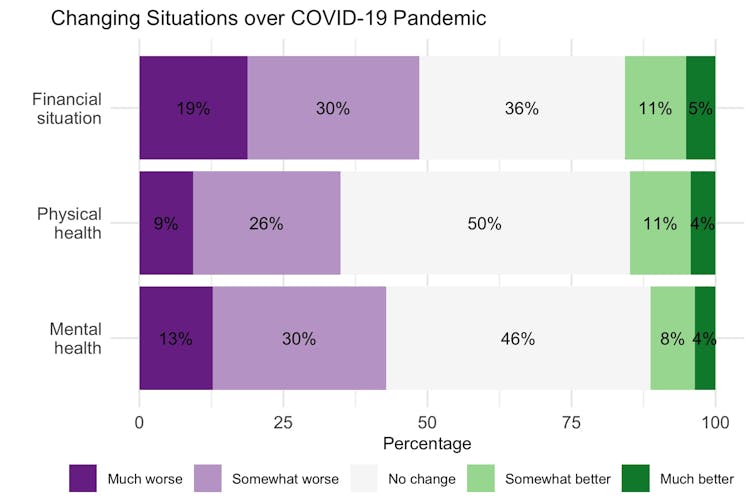

The last three years have taken a toll on many Albertans. When asked to consider how their financial, physical and mental health situations have changed over the course of the pandemic, 49 per cent said they experienced worsening financial situations, 35 per cent saw declines in their physical health and 43 per cent thought their mental health was worse in January 2023 than in March 2020.

With these financial impacts, many Albertans had trouble managing their expenses and paying their bills over the pandemic. These struggles were more obvious early in the pandemic — in August 2020 — and in more recent months. Throughout, 38 to 48 per cent of Albertans had trouble meeting their monthly expenses, but these experiences differed across groups.

Over time, the situation appears to diverge by both gender and education. Similar percentages of men and women and people with and without university degrees had trouble meeting expenses in August 2020, which could be linked to larger economic struggles early in the pandemic.

Over time, however, women and people with less education were more likely to report economic struggles. Older adults and members of the so-called silent and boomer generations — those born before 1964 — were also much less likely to experience economic insecurity throughout the pandemic, emphasizing age divides in pandemic experiences.

Looking back on the province’s pandemic response, Albertans were often divided about what approach the government should take, with some advocating for more stringent measures and others arguing that the measures in place were too harsh.

Controversy over the pandemic response caused internal divisions in the governing United Conservative Party that eventually resulted in Jason Kenney stepping down as premier during his first term in office.

Divided views

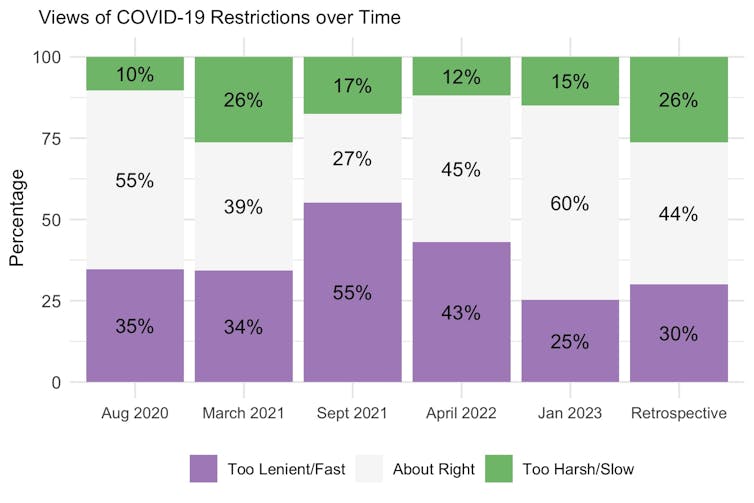

The Viewpoint Alberta surveys show that over the three years of the pandemic, a sizeable group — ranging from 10 to 25 per cent — consistently believed that the pandemic measures were too strict. An even larger group — ranging from 25 to 55 per cent — thought the measures weren’t strict enough.

It was only at the end of the first wave of the pandemic — when measures were being relaxed — and in January of 2023, when most measures had been removed for almost a full year, that a majority of respondents thought the measures in place were “about right.”

We asked survey respondents to evaluate four organizations that were important to the pandemic response, scoring them on a scale from one (poor) to 10 (excellent). They gave each a passing grade, but not a strong positive endorsement. Alberta Health Services and the Chief Medical Officer of Health scored highest, while the provincial and federal governments fared worse.

Not surprisingly, most respondents now believe that Alberta is more divided than it was in March 2020. Almost 40 per cent said they thought the province was somewhat more divided, and another 32 per cent thought it was much more divided. Only eight per cent thought it was more united.

Despite the dominant beliefs that Alberta has grown more divided, survey results also showed a growing optimism about Alberta’s future. In August 2020, only 35 per cent of respondents were optimistic. By January 2023, half of Albertans were optimistic about the future.

The road ahead for Alberta

Many Albertans have struggled over the past three years — financially, socially and physically. The pandemic has taken its toll on many people. But, on the eve of a highly consequential provincial election in May, there is a growing sense of hope across the province.

The pandemic isn’t likely to be an issue on the campaign trail, but it has shaped public attitudes in ways that matter.

One challenge for parties in the 2023 election will be to harness the fragile sense of optimism: things were bad, but the future is bright. A party able to make a plausible case that it would heal the divisions might harness this sense of optimism in the campaign.![]()

Michelle Maroto, Associate Professor of Sociology, University of Alberta and Lisa Young, Professor of Political Science, University of Calgary

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.