Kristof Titeca, University of Antwerp

A great deal has been written about the Ugandan rebel group, the Lord’s Resistance Army. Under their commander, Joseph Kony, the group became notorious for its brutal violence and use of child soldiers. But few images of the group are available. Those that are were mostly taken during peace negotiations between the government of Uganda and the Lord’s Resistance Army in Juba, Sudan, in 2006.

My newly published book Rebel Lives. Photographs from inside the Lord’s Resistance Army, aims to change this. It consists of photographs taken by Lord’s Resistance Army commanders themselves. It gives an unprecedented view into the lives of those involved in the rebel movement.

The Lord’s Resistance Army emerged in opposition to President Yoweri Museveni’s newly formed government in the late 1980s. But the group turned against the people they claimed to protect, particularly during the 1990s and 2000s. They abducted civilians – mostly children – on a large scale. Boys and men were used as fighters, whereas girls were given as “wives” to commanders.

The photographs were mainly taken in 2002 and 2003, when the Ugandan army chased the rebels from their bases in southern Sudan. Sudan’s president, Omar al-Bashir, supported the rebels and allowed them to launch attacks into Uganda from bases in southern Sudan. The Lord’s Resistance Army re-entered northern Uganda, expanded their territory, established new bases and looked for potential new allies.

The photos are testimony to this period. Most were taken by two of the highest commanders – Charles Tabuley and Vincent Otti – who were in charge of this mission.

The photos have a profound ambiguity. They illustrate the tension between extreme violence and the everyday lives of the rebels. They show abducted young men and women who have been exposed to large degrees of violence – and who have been committing these acts themselves. At the same time, they also show how, within this context of extreme violence, life continues to be surprisingly ordinary.

Collecting photographs

I collected the photographs during many years of research in the region. They came from various people including former rebels, traditional and religious leaders and journalists.

For the past three years, I have worked with a local research team (led by a former rebel) to trace the former soldiers in the photographs: to ask for their permission to use the photographs and understand their meanings. We found a great deal of information from female ex-LRA members, who usually stayed longer in the rebel group. As “wives”, most of them spent less time on the frontlines, which offered them less opportunity to escape but also made their situation relatively safer.

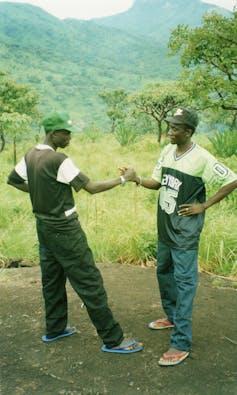

Many of the photographs are of a striking normality: they depict scenes of families posing during celebrations, young men trying to look cool, young women showing off their nicest dresses and couples in love.

They make for uncomfortable viewing. These ordinary scenes were being photographed against a backdrop of great violence. The Lord’s Resistance Army brought suffering and pain to civilians in northern Uganda, and beyond. They slaughtered, looted, abducted, burned, raped and disfigured people. Moreover, the rebels themselves had been exposed to extreme violence within the LRA, as most of them were abducted.

The normality of their photographs isn’t unsurprising. War reporting and analysis often focuses on the spectacular: on violence, suffering, and horror. But in between these moments, there’s an “everyday”, in which people live ordinary lives.

Conflicts also constitute a time of intense bonding between members of armed groups, as dangers and sorrows are shared, protection is sought, and friendships are made.

Memories

When discussing the photographs with the former rebels, I would often get surprising reactions: some of the former rebels spoke of their time in the army with a certain melancholy.

They spoke about friendships they nourished, spiritual miracles they witnessed and the power they felt. They would speak of the nice clothes they had, and the celebrations they organised.

At first sight, the photographs mirror practices in wider Ugandan society, and are not very different from ordinary family photos. They show people posing as friends, in pairs, suggesting a familial bond.

They show people dressed at their best, posing for a photo on a “big day”. In the words of a former rebel:

We particularly put these clothes on special days like Christmas and Juma Oris (one of Kony’s spirits, named after a Ugandan military officer) day – the 7th of April, which is the day when Kony has gone to the bush. That day is a good day: you eat well, and you look smart. We put our nice clothes on, and we have our photo snapped. The bigger commanders, some of them would dress very nicely!

Photographs and coercion

Yet, at the same time, the photographs reflect the violence and coercion of which they are part. For example, the photographs show the pleasure of certain individuals, but not of everyone: not all fighters had nice clothes to pose in, or the opportunity of posing in front of a camera.

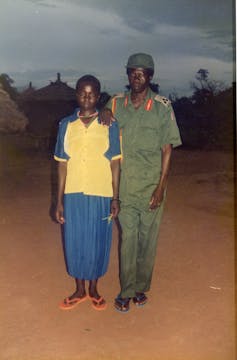

The clothes worn show the inequality, particularly among the women: the clothes were looted by the men, and not equally distributed among the women. The better their rank, or the higher the rank of their “husband”, the better their access to the nicer clothes.

In the words of a former (female) rebel:

In the bush, we had very nice clothes. A nice dress means that the husband loves you. They come to Uganda, and they get all these clothes, and they take it to the bush. The choice to do so is out of love. Sometimes a man has eight wives; he only gives to his favourites. This often provokes jealousy: the other wives could not get any of the nice clothes, and they also could not pose for the photo. It only were the favourites who were able to do so!

Given the fact that clothes were often the result of looting, they themselves are a testimony to the violence both outside and within the army.

For some, the act of being photographed was outright negative: not everyone felt happy posing in front of the camera. For them, it was not a choice, but a reflection of the forced circumstances of which they were part.

The photographs force us to further think beyond binary terms such as victims or perpetrators. It has been widely discussed how these categories are difficult to maintain for combatants of the Lord’s Resistance Army, who can be considered both a victim (of abduction), and a perpetrator (having participated in the violence).

Within the coercive and violent limits of their existence, combatants still have a number of identities and encounter a multitude of experiences. They are confronted with the most brutal violence, suffer a range of mistreatment, but in a number of cases also fall in love, argue, and look for ways to relax or find pleasure.

The photographs are very much witness to these multiple experiences.![]()

Kristof Titeca, Senior Lecturer in International Development, University of Antwerp

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.