The notion that enjoying a casual beer or sipping on your favourite wine could not only be harmless but actually beneficial to one’s health is a tantalizing proposition for many. This belief, often backed by claims of research findings, has seeped into social conversations and media headlines, painting moderate alcohol consumption in a positive light.

As researchers at the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, we find ourselves frequently revisiting this topic, delving deep into the evidence to separate fact from wishful thinking. Can we confidently say, “Cheers to health?”

Unpacking beliefs about moderate drinking

The commonplace belief that moderate drinking can be beneficial to health can be traced back to the 1980s when researchers found an association suggesting that French people were less likely to suffer from heart disease, despite eating a diet high in saturated fat.

This contradiction was thought to be explained by the assumption that the antioxidants and alcohol found in wine might offer health benefits, leading to the term “French paradox.”

This concept reached a broader audience in the 1990s, following a segment on the American news show 60 Minutes which had a profound impact on wine sales. Later research expanded on this idea, suggesting that frequently drinking small amounts of any type of alcoholic beverage might be good for health.

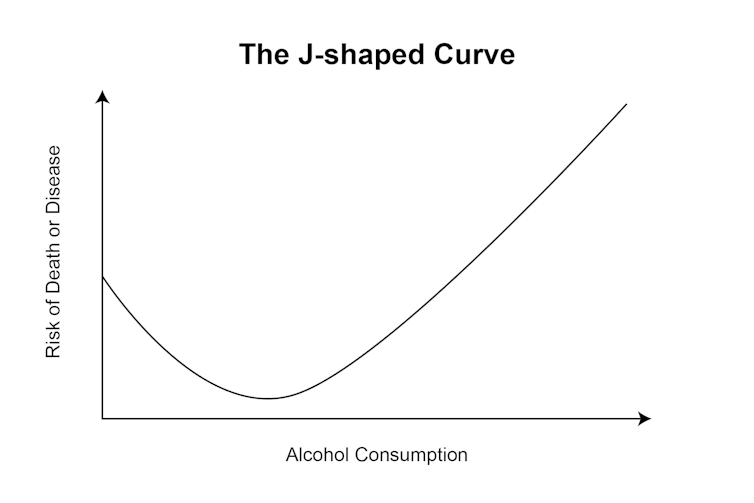

This idea was formalized into what is now known as the J-shaped curve hypothesis. Put simply, the J-shaped curve is a graphical representation of the apparent relationship between alcohol consumption and death or disease. According to this model, abstainers and heavy drinkers are at higher risk of certain conditions, such as heart disease, compared to moderate drinkers, whose risk is lower.

Current perspectives on moderate drinking

People used to think that tobacco use was good for health, historically describing it as a remedy for all disease. As scientific understanding has advanced, however, tobacco use has been increasingly recognized as a leading cause of preventable disease and death.

Like tobacco, alcohol was once used in medicine and has since become recognized as a major cause of preventable mortality and illness. For instance, recent global estimates suggest alcohol is responsible for 5.3 per cent of all deaths.

Furthermore, in Canada, the revenue generated from selling alcohol does not come close to covering the damage it causes, leaving the government $6.20 billion short every year. However, much of these costs can be attributed to heavy drinking.

So where does this leave moderate drinkers? We recently set out to answer this question by analyzing data from over 4.8 million people from more than 100 studies, covering more than 40 years.

We found that many studies exaggerate the benefits of moderate drinking due to methodological flaws known as selection biases. No matter if we analyzed the studies as one big group, using statistical methods to try and lessen these mistakes, or if we separated the good studies from the not-so-good ones, one thing was clear: moderate alcohol consumption does not appear to offer the health benefits once believed.

Explaining the contradiction

Selection biases represent data distortions caused by how research participants are selected. Such biases lead to unfair comparisons between groups, which skews analyses towards finding a J-shape curve. Essentially, it is like comparing two runners in a race, where one wears heavy boots and the other wears lightweight running shoes. Concluding that the second runner is more talented misses the point; it is not a fair comparison.

Here are five examples of selection bias in the context of the alcohol J-shaped curve which can accumulate as people age:

Poor health, less alcohol. As health declines, especially in older age, people often reduce their alcohol consumption. Not distinguishing between those who cut back or quit for health reasons can falsely indicate that moderate drinking is healthier.

Unhealthy lifetime abstainers. Comparing moderate drinkers with individuals who have never consumed alcohol due to chronic health issues may falsely attribute health advantages to alcohol consumption.

Moderate in other ways. Moderate drinkers often lead balanced lifestyles in other areas, too, which may contribute to their perceived better health. It is not just moderate drinking, but also their healthier overall opportunities and choices, such as better health-care access and self-care, that make them seem healthier.

Measurement error. Assessing alcohol consumption over a short period of time, like a week or less, can lead to a misclassification of drinkers. Heavy drinkers who happened to not consume alcohol during the week of assessment would be incorrectly classified as abstainers, for example.

Early alcohol-attributable deaths. The inevitable exclusion of individuals who may have died from alcohol-related causes before a study of older people starts can result in a “healthy survivor” bias, overlooking the earlier detrimental effects of alcohol.

Continuing the conversation

We should be skeptical of results suggesting that moderate drinking is healthy because selection biases can muddy the waters. For instance, multiple implausible J-shape curve relationships have been published, including between moderate drinking and liver disease.

We are well aware that this news might not be what you were hoping to hear. It might even stir up feelings of unease or skepticism. For many people, limited alcohol consumption is enjoyable. However, it is not without risk and it is important for people to understand these risks to make informed decisions about their health.

The risks are reflected in the 2023 Canadian Drinking Guidance. The guidance attempts to “meet people where they are at,” suggesting that one to two drinks per week represent a low risk of harm, three to six drinks a week represent a moderate risk, and seven or more drinks a week represent an increasingly high risk. Ultimately, they enable people to make informed decisions that best suit their health and well-being.![]()

James M. Clay, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, University of Victoria and Tim Stockwell, Scientist, Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research and Professor of Psychology, University of Victoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.