Christian-Georges Schwentzel, Université de Lorraine

In September 2019, a French ad for feminine hygiene products featuring taboo-breaking representations of vulvas and menstruation sparked controversy. Yet in a cultural context in France, phallic symbols rarely cause a fuss. What explains this difference in treatment?

Images of male genitalia in art and advertising rarely cause a stir – we’re used to them. Male statues have been flaunting their (fairly realistic) penises in public parks for centuries, and Perrier often centers its ads on phallic-shaped bottles.

In contrast, vulval symbols are conspicuous by their absence. No wonder, then, that the Nana brand’s “Viva la Vulva” campaign is causing a stir. The phallus is seen as a powerful image, whereas the vulva is upsetting to many. But this has not always been the case.

The divine vulva of Ishtar: a fertility symbol

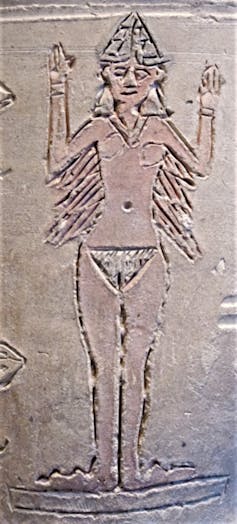

In the third millennium BC, the Sumerians, inhabitants of present-day Iraq, worshipped the goddess Ishtar. Poetic texts refer to the goddess’ wet vulva, fertilized by the sperm of her mortal husband, Dumuzi, the shepherd king.

The goddess addresses her lover as follows:

Who will plow my high field?

Who will plow my wet ground?

As for me, the young woman,

who will plow my vulva?

Who will station the ox there?

The oxen pulling the plow refer to the king’s phallus; the vulva represents the ground to be sown. Ishtar’s royal lover answers, “I, Dumuzi the King, will plow your vulva.” At fever pitch of excitement, the goddess cries, “Then plow my vulva, man of my heart!”

They make love, and when Dumuzi ejaculates, plants are seeded all around and begin to grow. The vulva plays a positive role in this story; it is complementary to the phallus, equally necessary to the fertilization of the land.

In ancient Egypt, the vulva was seen as a source of happiness and regeneration. The sun god Ra was the source of light on Earth, but he sometimes showed signs of weakness, endangering all of humankind. Fortunately, the beautiful goddess Hathor had the bright idea of undressing in front of him and showing her vulva. Ra laughed joyfully at the sight and recovered all his dazzle. A valuable vulva indeed…

In Greece and Rome: the vulva vanishes

The vulva fell out of favour in the ancient Greek and Roman world. Artists often depicted the phallus, but the vulva is almost nowhere to be seen. Gods and heroes flaunt their penises, but goddesses tend to be robed; even when nude, like Aphrodite, they have perfectly smooth pubic triangles, with no clitoris or labia. The vulva was lost to censorship.

By contrast, the phallus – phallos in Greek or fascinus in Latin – was revered. Believed to have magical powers, it was exhibited and worshipped as an idol capable of protecting the city and its inhabitants from harm, and putting thieves and intruders to flight.

This is why the Athenians held the annual Dionysia festival, where a solemn procession of citizens called phallophoroi carried giant carved wooden phalluses. Erect penises made of wood or clay were also installed on street corners and at the entrances to stores and houses.

A sign found over the entrance of a bakery in Pompeii shows a fascinus, framed by an inscription proclaiming “Here dwells happiness” (Hic habitat felicitas). Phallic scarecrows were thought to be apotropaic (able to ward off evil), and Greeks and Romans wore bronze penis-shaped pendants. In all these different forms, the phallus was always synonymous with strength, happiness and prosperity.

The vulva, for women only

In Greek art, depictions of the vulva – believed to boost female fertility – are only found on objects intended for women.

Statuettes of pregnant women touching their vulvas have been found in Egypt. Other figurines of vulva-women, found in Asia Minor, were probably worn by pregnant women as protective amulets. The ethnologist and psychoanalyst Georges Devereux associated these headless figurines, whose faces are engraved on their bellies, with the myth of the priestess Baubo, who showed her vulva to Demeter to distract the goddess from her grief at the loss of her daughter.

Like Ra in the Egyptian story of Hathor, Demeter reacted by laughing–but Baubo showed her vulva as a gesture of female solidarity, with no erotic intention.

The denigration of the vulva outside the female sphere is illustrated by the birth of the goddess Athena, who was growing in Zeus’ skull. One day, Zeus had such a headache that he begged the god Hephaestus to split open his skull with a hammer and chisel. Hephaestus complied, carving out a sort of improvised vulva.

The goddess Athena, in full armour, sprang out from this crack – so the lord of the gods was able to give birth to his daughter, proving the vulva’s worthlessness. This myth is a fantasy of male birth-giving – procreation in which the vulva plays no part.

The “taut sex” of the nymphomaniac

But the most hostile ancient representations of the vulva are found in Latin texts. Roman authors imagined nymphomaniac characters, women gripped by uncontrollable sexual frenzy. One such example is Messalina, wife of the emperor Claudius (reigned AD 41-54). After her death, she became the heroine of a sinister legend portraying her as sexually insatiable.

The poet Juvenal described her orgiastic behaviour in his Satires, recounting how the young empress left the splendour of the palace under cover of night, venturing out in secret to gratify her lust in a sordid Roman brothel (Juvénal, Satires VI, 116-130).

All night long, Messalina took lover after lover, only stopping when the brothel closed its doors. She returned to the palace with her “taut sex still burning” (adhuc ardens rigidae tentigine vulvae), exhausted but “not satisfied” (sed non satiata, the famous expression that inspired Baudelaire’s poem of the same name).

Her lust never satisfied, Messalina involved her entourage in her excesses. According to Pliny the Elder, she challenged a prostitute to a 24-hour sex competition, which she won with a score of 25 partners (Natural History 10, 83, 172).

In addition to her endless string of lovers, Messalina was reputed to always initiate her sexual encounters, revolutionising the codes of phallocratic Roman society. She was portrayed as a tireless sexual predator and a dominant woman who behaved like a man – outrageous in Roman eyes.

Claudius was told of his wife’s shocking behaviour and ordered her execution – the only way of quenching her sexual thirst.

So what is obscenity?

Obscenity is a social construction that varies according to time and place. In Hindu mythology, the yoni is the symbol of the fertility goddess Shakti, who was was revered as far back as 4000 BC. It was seen as equal to its male counterpart, the lingam, and together they were the source of all existence. A similar mythology is present in Japan with the concepts of yin and yang, representing female and male energies. At the same time, the country still considers images of vulvas to be obscene from a legal point of view, as demonstrated by the 2014 conviction of the artist Megumi Igarashi.

But thanks to the influence the influence of female artists – and even advertisers – the vulva is back in the 21st century.

Translated from the French by Sally Laruelle of Fast ForWord and Leighton Kille of The Conversation France.![]()

Christian-Georges Schwentzel, Professeur d'histoire ancienne, Université de Lorraine

Cet article est republié à partir de The Conversation sous licence Creative Commons. Lire l’article original.