Karen Malone, Swinburne University of Technology

Leaders across the country – particularly in the states with the largest outbreaks, New South Wales and Victoria – have designed road maps towards reopening the states after long lockdowns. Safety in childcare, schools and universities is a core component of reopening plans.

Year 12 students in Melbourne go back to school this week, and there are staggered return plans for the rest of the year levels over the coming weeks. All students are set to return to the classroom full-time by November 5.

Regional Victorian students have a different schedule with all students back in the classroom full-time by October 26.

NSW students will be returning to class in a staggered fashion too. Kindergarten, year 1 and year 12 students are to return on October 18; all other grades will return on October 25.

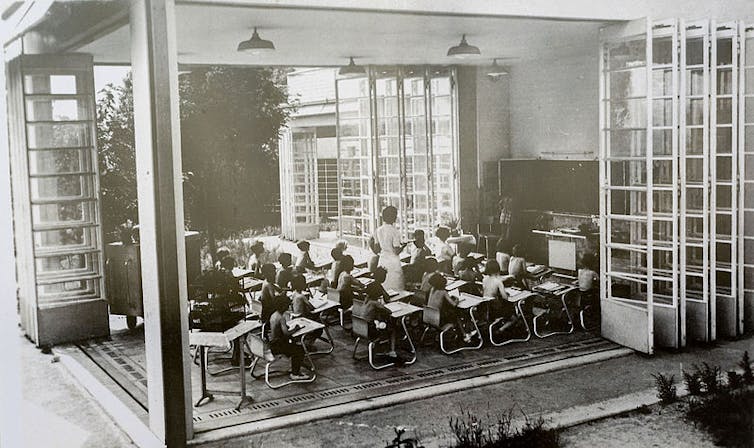

Managing a safe return includes managing indoor classrooms via ventilation, sanitation and social distancing. But the NSW Education Department has said it will also support schools to use “outdoor learning areas”. And the Victorian strategy includes advice for early childhood centres and services to “move to an indoor/outdoor program (shifting to as much outdoor programming as possible)”.

Read more: From vaccination to ventilation: 5 ways to keep kids safe from COVID when schools reopen

Moving classrooms outside is not a new idea. It has been done in past disease outbreaks such as tuberculosis and the Spanish flu. We can learn lessons from history and take pointers from international schools that have already made moves to learn outside.

A history of outdoor education

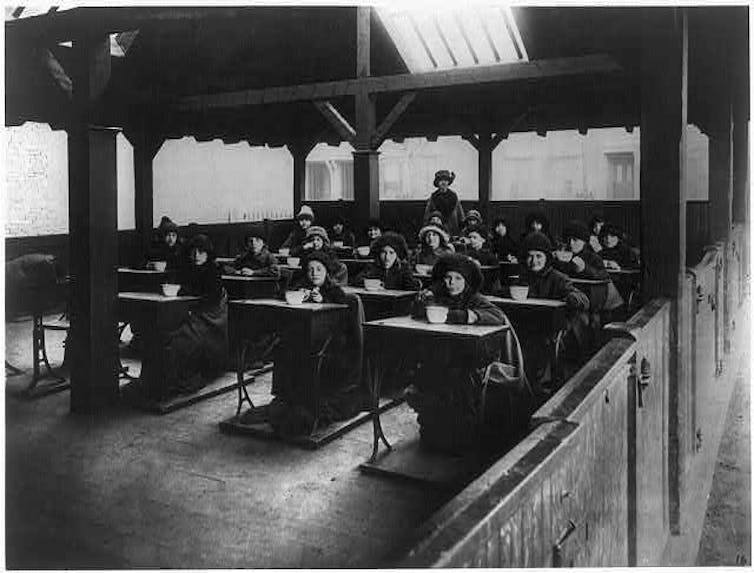

As tuberculosis was spreading and taking a toll on children in the early 1900s, an open-air school movement was launched in Germany. In 1904, the Waldschule (forest school) opened in Berlin. Its success spread, with forest schools opening in Scandinavia and open-air schools in Britain. A nationwide movement for fresh-air schools was launched across the US a few years later.

In 1912 New York, a private school moved classes onto the roof. Another school took up classes in an abandoned ferry and another in Central Park.

Schools around the world are now using outdoor classrooms again as a key strategy to mitigate the risks of COVID while remaining open.

The US National COVID-19 Outdoor Learning Initiative has been pushing for schools to have classrooms outdoors and many have done so.

By last October New York City officials alone approved 1,100 proposals for public school students to spend at least part of their day outdoors.

Some wanted to use their school grounds, closed down streets or take students to local parks for lessons. Essex Street Academy, a public secondary school in Lower Manhattan, was one of these schools. Students have been taking multiple classes on the expansive roof. According to the principal of the school, the roof of the vertical schools was designed as a school yard – so nothing needed to be adjusted.

Read more: Physical distancing at school is a challenge. Here are 5 ways to keep our children safer

Without any specific directions, many teachers around Australia have also been heading outdoors. A K-1 primary teacher in NSW told me:

Since the pandemic, on the days I’m onsite, I keep the kids outside most of the day. We go into the garden and read stories, complete writing tasks, art and maths games – using the gardens as stimulus.

A university lecturer in Victoria said:

Last semester, to support social distancing and increase fresh air, I took classes outdoors. Our classroom was the campus grounds, a local park, the botanic gardens and the National Gallery.

Here are seven reasons why schools should be moving classes outside as much as possible.

1. Being outdoors supports students’ health and well-being

Being outside lowers the risk of transmission of the virus by making it easier to socially distance and providing better ventilation and fresh air.

It also supports students’ mental well-being. Research shows being outside has many positive health, social, emotional, ecological and learning benefits for students and staff.

2. Setting up an outdoor classroom is relatively inexpensive and easy

Compared to the other options such as opening up walls or windows in classrooms, installing ventilation systems or rotating home/school attendance to ensure smaller class numbers, moving outdoors can be implemented with limited resources.

3. Outdoor classrooms may mean schools stay open

Schools could safely accommodate more students by going outside. Therefore, there is less likelihood of disruption to the lives of students and families. By lowering risks once students return, schools are more reliably able to remain open.

4. What is normally taught indoors can be adapted for outside

For early childhood and primary school everything can be outside. Experiences overseas have shown well-resourced roof spaces or pavilions have overcome issues of special equipment.

The question should be what really can’t be taught outside rather than what can – that is the shorter list.

Read more: Children learn science in nature play long before they get to school classrooms and labs

5. Schools can use a variety of outdoor options

Permanent outdoor classrooms could be set up. Students could use the outdoors for one-off classes during the day, or schools can stagger class numbers by scheduling small groups inside and out throughout the day.

6. Any space outdoors can be used

Around the world, we’ve seen verandahs or external corridors, decks, courtyards, roof tops, school grounds, gardens, ovals, blocked-off streets on school boundaries, nearby local parks and playgrounds, and a vast array of other local community spaces, such as beaches, forests and village centres, used as outdoor classrooms.

7. Educators from outside the school can be used

Educators from national parks, aquariums, museums, zoos and science centres are already trained in teaching outdoors and many have had limited work due to pandemic closures.![]()

Karen Malone, Professor, Environmental Sustainability and Childhood Studies, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.