On the evening of January 26, 2007 anti-death sentence activists gathered outside Changi prison with candles and roses hoping their last-ditch attempt to put pressure on the Singaporean government to spare the life of 21-year-old Iwuchukwu Amara Tochi would yield positive results.

This little hope was soon dashed when Singapore’s Central Narcotic Bureau confirmed that Amara had died from hanging after he was found guilty of drug-trafficking, a crime many believe he did not commit.

This sparked international outrage. The United Nations and the Nigerian government through then president, Olusegun Obasanjo, had reached out to Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong 48 hours before the execution to ask for leniency but this was denied. Instead, the Singaporean leader said it was a decision that was not taken lightly.

Early Life

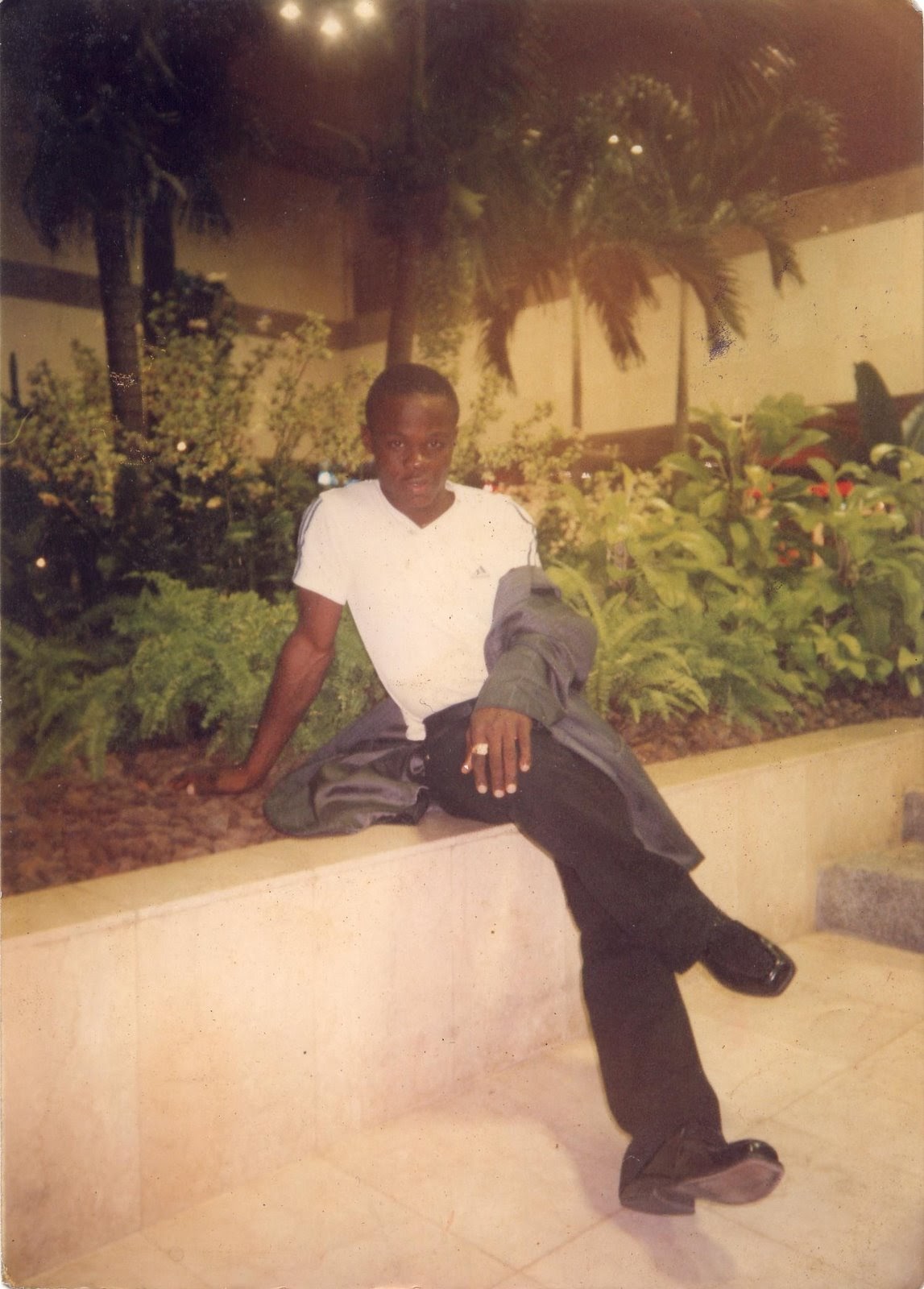

Tochi always wanted to play football. It was both a passion and a way to escape the poor life he had become tired of. Born in 1985, he had to move in with a relative at the age of five where he attended St Anthony’s Mission School in Ohafia, Abia state. His brother on the other hand dropped out of school so as to help their father.

As a young boy, Tochi saw football as both a passion and a way to earn money to bring his family out of poverty. Photo: YouTube/IntegrityTV.

At age 14, Tochi went to Senegal to start his professional career and played for Nigeria in the West African Coca-Cola Cup Championships. From there, he sent a sizable portion of his wage back home to help his family.

In a bid to get better placement, Tochi decided to go to Dubai as he believed the city would offer him a more productive footballing career. He decided to go to Pakistan on the assumption that he would secure a visa and a train ride to Dubai. It wasn’t until he got there he found out that no such train service existed.

Unable to execute his plan, Tochi sought help from a church in Islamabad where he was granted refuge. It was while he was there he met one Mr Smith, another Igbo Nigerian, who would change the course of his life forever.

Smith provided Tochi with some food and pocket money and promised to help him secure a visa to Dubai. All efforts to do so however failed as Tochi did not meet the requirement. Smith asked Tochi if he would go to Singapore instead where he would meet his sick friend and help deliver African herbs. While in Singapore, Tochi would be able to continue his footballing career by applying for trials at clubs over there. Smith also said the sick friend, Okeke Nelson Malachy, who would be flying from Indonesia would also give Tochi $2,000. This deal seemed reasonable to Tochi who also saw it as an opportunity to get out of Pakistan where he had been stranded.

Arrest

On November 27, 2004, Tochi flew into Changi Airport in Singapore at about 1:45pm. He was supposed to meet with Malachy who was flying in from Indonesia and hand over the package which he believed contained African herbs as he had been told. However, after waiting at the airport lounge for a long time, a call from Smith confirmed that Malachy would be arriving late as he missed his flight. He decided to go to the Ambassador Transit Hotel to book a room and wait.

However, no rooms were available and he decided to wait till he could get one. By the time one was available, it was already more than 24 hours. The receptionist as per procedure, informed the police of the presence of someone who had been in the transit area for more than 24 hours. When the Airport police arrived and questioned Tochi, he explained that he was required to have $2,000 before he can be granted entry into Singapore which he did not have at the moment. He added that he also intended to speak with the football federation for assistance in getting to play for any of the clubs there.

Tochi stayed at Changi Airport for more than 20 hours waiting for Malachy to deliver “African Herbs” to him Photo: Execution Today.

The officer then proceeded to search Tochi and found in his possession about 100 capsules. He asked Tochi what they were for and he responded that they were African herbs that would give someone energy when consumed. He added that he was supposed to deliver it to Malachy. To prove to the police that the drug was harmless, Tochi swallowed one of the capsules and had to be rushed to the hospital where he was given a laxative to flush it out.

According to court documents examined by Neusroom, Tochi was taken back to the hotel where he was asked to place a call through to Smith. The latter told him Malachy would soon arrive. By then, officers of the Central Narcotics Bureau had been called. When they cut open the capsules, they discovered that they contained more than 300 grams of heroin.

Tochi was asked to place another call to Smith who, unaware of the police involvement, confirmed that Malachy had arrived at Singapore and was waiting near a café to receive the package. Police swooped in and arrested him too.

Trial and death sentence

One of the first things Tochi did as soon as it dawned on him that he was in serious trouble with the law was to put a call through to his brother in Nigeria. Although the police confirmed that Mr Smith was in Pakistan, they were unable to unravel his identity.

According to Singaporean law, section 17 of Misuse of Drugs Act stipulates that anyone found with more than 2 grams of heroin is presumed to be trafficking it

At the trial which began in March 2005. Tochi’s defence argued that he could not have known that the content of the capsules was heroin. If he did, he would not have stayed in the transit area for more than 24 hours. Also when he was informed that the police had been notified he would have either run away from the hotel or dispose of the drugs. The defence also noted that Tochi swallowed the capsule to prove to the police that they were African herbs which he had been made to believe when in fact it was heroin.

The judge Mr. Kan Tin Chiu, in his commentary, said he did not think Tochi knew he was being asked to transport drugs by the so-called Mr Smith.

He made the following findings at paragraph 42 of the judgement (2005) SGHC233:

“There was no direct evidence that he knew the capsules contained diamorphine. There was nothing to suggest that Smith had told him they contained diamorphine, or he had found that out of his own.”

Despite this however, the judge said Tochi should have known when he was promised $2,000 that something sinister was going on. He said Smith was not a particularly rich man and so Tochi should have been wary of his offer of that sum for simply helping to deliver a package to someone else.

He noted that Tochi knew that “Smith was a man who would break the law as Smith had arranged for false visas and endorsements to be entered into the first accused’s passport to facilitate his travels. He must have realised that Smith was offering him much more than was reasonable for putting him through the minor inconvenience of meeting up with Marshal at the airport terminal and handing the capsules to him. He should have asked to be shown and be assured of the contents before agreeing to deliver them, and he could have used the ample opportunities he had when he was in possession of the capsules to check them himself, but he did nothing.”

The judge also noted that Tochi was not a young naïve person as he had left his home country, Nigeria, as a young man to fend for himself in Senegal before again making the move to Pakistan.

In Malachy’s case, the judge did not accept his defence despite his claim that he did not know either Smith or Tochi. He claimed he had only come to Singapore to buy used vehicles to sell in South Africa where he came from. It was however proven that his South African document was a forgery and he was declared stateless although he was considered a Nigerian by many due to his name.

The judge sided with the prosecutor that the duo with their action had contravened the law on Misuse of Drug Act and had intended to traffic the substance into the country and sentenced them to death.

International Reaction and Execution

The death sentence issued to the duo particularly Tochi whom many felt was innocent sparked reaction and international outrage. Although the case automatically went to the Appeal Court, many saw it as mere formality and it soon turned out to be so as he lost the appeal. From then on, it became a countdown. The United Nations Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, Philip Alston, in a statement said Tochi’s guilt could not be clearly established and thus should not be executed.

“The standard accepted by the international community is that capital punishment may be imposed only when the guilt of the person charged is based upon clear and convincing evidence leaving no room for an alternative explanation of the facts. “Singapore cannot reverse the burden and require a defendant to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that he didn’t know that he was carrying drugs.”

A lawyer from Nigeria, Princewill Akpakpan, took the long trip to Singapore but he was not granted the chance to set sight on the condemned young man and had to return to Nigeria.

Then president Olusegun Obasanjo went on a trip to Singapore. He met with the Prime Minister to discuss Nigeria’s potential oil export to the Asian country. There, Obasanjo mentioned the planned execution of Tochi and called for it to be commuted to imprisonment. He made reference to Nigeria’s excellent relationship with Singapore

He said: I earnestly urge you to reconsider the conviction … and to commute the death sentence to imprisonment.”

The Prime Minister expressed regrettably that there was nothing he could do to stop the planned execution.

A few days before the planned execution, a letter was sent to Uzonna, Tochi’s brother informing him and his family that they would be granted an extended visiting period for three days. Of course, it meant little to them as they did not have the money to fly to Singapore.

Tochi’s parent and siblings could not afford the flight to Singapore to witness his execution. Photo: Singapore Democratic Party.

On the evening of Thursday, January 25, 2007, several activists gathered in front of Changi prison with candles. One of them was a lawyer and activist, Madasamy Ravi who had had the opportunity to speak with Tochi in prison. In his hand was a football jersey and short which he hung on the fence of the prison that belonged to the convicted young man. They held a vigil there all night until the dawn of Friday, January 27. Just before 6am, a prison official came out and announced the execution of Tochi and Malachy. Tochi reportedly cried for five minutes asking the priest to pray for him before he was executed. A simple funeral service was held St MaryMount Concent Chapel before he was buried at Chua Chu Kang Cemetery.

Smith has not been found…yet.

Before his execution, Tochi cried for 5 minutes asking the priest to pray for him. Photo: Singapore Democratic Party

Finding Ravi

I first came across Tochi’s story in 2015 when it was referenced in another story about a Nigerian facing the death penalty in Singapore, Chujioke Stephen Obioha. What first caught my attention was his age: he was arrested at 18 and executed at 21. I became interested in Tochi’s story and started to surf the internet. However, very few comprehensive reports were done about him beyond the story of his arrest and execution.

When this story was approved for me to work on, I knew I could not just retell the same story everyone had put out there. I had to go a step ahead and know who Tochi really was before his death; his family especially his brother, Uzonna; Princewill Akpakpan who flew to Singapore but was not granted the opportunity to see him. And I had to find out more about Mr Smith.

But it would be M. Ravi, the Singaporean lawyer and activist that I would find and through him, the story would take another direction.

I started by reading every scrap of information I could find online and noted down names of people and places involved in the case. I searched for Tochi’s school, St Anthony’s Mission School, on Facebook and discovered numerous old student association groups. I sent messages to all the admins but got no response from any of them.

Next, I sent separate mails to Nigeria’s Diaspora Commission, the Nigerian High Commission in Singapore and the Singaporean Ministry of Foreign Affairs but got no response. I set an email to the Civil Liberty Organisation in Nigeria which also played a significant role in creating awareness about Tochi’s plight but got no reply. A search for Princewill Akpakpan’s name did not turn up any contact. It looked like I was going to end my search and be left with a story that every other person had told. As a last resort, I checked out M Ravi on the internet and saw he was quite a popular figure with a Wikipedia page. I read his profile and soon saw the connection to Tochi: He was an anti-death penalty crusader, activist and Singaporean lawyer who seemed to have been involved in the case till the execution.

I saw his LinkedIn profile and sent him a message telling him I wanted to talk to him about the Tochi execution that happened almost 15 years ago. He replied almost instantly. He recalled his campaign for Tochi and how it brought him to Nigeria. That was a new one for me as I was not even aware he had come to Nigeria. He then said he would send me his book, Kampong Boy, where he dedicated a chapter to Tochi. He suggested I read it first before our conversation.

The book proved to be very important in providing a personal perspective about Tochi. The chapter dedicated to him titled: A Tragically Fallen Star chronicled Ravi’s involvement in the case, his pro-bono campaign, visit to Nigeria to speak at the National Assembly and ultimately, Tochi’s death.

M. Ravi became interested in Tochi’s case when he saw the judge’s comment that there was no evidence he knew he was carrying drugs. Photo: M. Ravi

According to Ravi’s account from his book, he first heard about Tochi when he read the Singapore Law Report in 2005 where his arrest and subsequent mandatory death sentence was documented. The judge’s comment that there was no evidence to suggest that Tochi knew the substance he was carrying was heroin piqued Ravi’s interest. He sprang into action and reached out to the Nigerian Civil Liberties Organisation and expressed his readiness to help Tochi. He spoke at the Nigerian embassy in Singapore and also got approval from Tochi’s brother, Uzonna, to represent him in Singapore before finally getting the chance to meet with the condemned young man.

Tochi’s brothers, M. Ravi and Princewill (L-R) Photo: M. Ravi

His meeting with Tochi was the first very personal non-journalistic view of the young man I came across. Ravi described him as innocent-looking and naïve which explained why he was very trusting of Smith and willing to deliver the fateful package. Ravi’s presence renewed his very slim hope and strengthened his resolve to push for the death sentence to be commuted.

From there, Ravi made the trip to Germany and then Sweden, Hungary creating awareness and calling the attention of the world to the impending execution before flying to Lagos, Nigeria. He met with Tochi’s uncle and brothers and Princewill of the CLO. From there, they flew to Abuja where they met with lawmakers to urge them to use their platform to push for Nigeria to take the case up at the International Court of Justice. He also appeared on TV with a member of the CLO for media exposure. He commented on the slow pace of how things moved in Nigeria in a case that required speed and action. By the time he left Nigeria, it did not look like much had been achieved especially on what was expected of the Nigerian government.

Before he left, he took with him Tochi’s jersey and shorts as symbolic items to show the world the young man had only been interested in football. He would ultimately hang them on the fence of Changi prison the night Tochi was executed.

Conversation with Ravi

After I read the chapter on Tochi, I got in touch with Ravi through a WhatsApp message. He called me almost immediately. The first thing he wanted to know after we exchanged pleasantries was to confirm what the time was in Nigeria.

“It’s half past two,” I replied.

“That’s fine then. It’s half past nine in the evening here in Singapore.

My first question was direct: “Do you think Nigeria did enough to help Tochi?”

His response came so quickly I felt convinced it was something he had thought of in the past.

“No, Nigeria did not do anything to help Tochi. If Nigeria had, perhaps, he would be alive today. I went to Nigeria, met with parliamentarians and tried to get the government to act but everything moved too slowly. I felt like a lobbyist. I had spent all my money working pro-bono to help Tochi. I even had to borrow money from a friend. You know your country is corrupt. I even had to pay journalists in your country to cover the story.”“When Nigeria finally acted, it was already too late because Singapore moves very quickly when it comes to the death sentence to show efficiency. In the US, someone can be on death row for a long time. This allows lawyers to test the law until all appeals and opportunities to commute the death sentence to imprisonment have been exhausted. “

I called Ravi’s attention to Obasanjo’s plea to the Singaporean prime Minister as proof of Nigeria’s attempt to help Tochi but he was very quick to dismiss it.

There was the case of a German woman, Julia Bohl, who was sentenced to death after she was caught with drugs in 2002. Following pressure from the German government, not only was her death sentence commuted to five years imprisonment but she was released after spending only three years in detention.

On the debate on death penalty, Ravi said it is something that should be abolished as it is wrong.

“It is wrong for a human life to depend on changes in law. The automatic death sentence for drug traffickers has been changed. Tochi may have been alive now based on this new amendment. That is why the death penalty wrong.”

I asked him about his meeting with Tochi and his voice softened. He described him as gentle, innocent and humble. “You know he wrote me a letter that was delivered to my office the evening before his execution.”

I interrupted him quickly because this was the first time I was coming across this information. Ravi said it was a letter of appreciation because he was one of the few people who had the opportunity of visiting him.

Tochi’s letter to M. Ravi written the night before his execution thanking him for his effort to get his death sentence commuted. Photo: Nicky Loh.

“Princewill tried to see him too but he was not allowed. I paid for Princewill to come to Singapore and see him but he was treated very badly. He was not allowed to see him because he was not called to the bar in Singapore.”

This was however not the case in the 2011 death sentence of Van Nguyen , a Vietnamese-Australian. His Australian lawyer, Lex Lasry, was granted permission to visit.

Ravi noted that Africans are disproportionately incarcerated in Asia and it has only gotten worse now.

Tochi’s jersey hung on the fence of Changi Prison the night before his execution. Photo: M. Ravi.

“Speak with Princewil,” Ravi continued. “He can tell you what he went through in their hands. We may not have been able to help Tochi then but we can try now. We can get the Nigerian bar Association involved and get Nigeria to take Singapore to the International Court of Justice and sue for wrongful death. I hope to one day come to Nigeria again and visit Anambra where Tochi grew up as I did not have the opportunity to do so during my first visit.”

Conversation with Princewill

It was Ravi who established a line of communication between Princewill and I. I had initially sent him a friend request on Facebook accompanied with a message detailing my interest in the Tochi story but got no response from him. I reached out to Ravi who ultimately sent Princewill a message on Facebook and told him about my interest in the Tochi story.

Princewill replied to my message a few hours later and accompanied it with his phone number. We also arranged a meeting at his office in Ikeja. When I got there, Princewill ushered me in and went straight to the point.

“Tochi should not have been killed. At worst, he should have been sentenced to life imprisonment. The death sentence being used in Singapore was handed over to them by the colonial British government. However, there is the issue of strict liability that should not be enforced in a case where the punishment is death. This is because if you find out that there was an error, you cannot bring back the dead.

“The Nigerian government, NBA, Nigerian High Commission to Singapore…they did nothing.” Princewill. Photo: Yusuf Omotayo.

There should be penal reform of the Singaporean law because it is sad when a state becomes an instrument of killing. The intent of a crime must be determined first. It was clear Tochi did not know the package he was given was drugs. If not, he would have left the airport.”

“Let us assume there is a fire right now and someone breaks into my office for safety purposes. Will the person be guilty of house breaking despite the fact that he broke the door to gain access? That is where intent is significant.

“The judge admitted that there was no evidence that Tochi knew about the drugs; yet he still gave a judgement that was contrary to his own observation’’.

I put the same question I asked Ravi to him about whether the Nigerian government did enough to save Tochi’s life.

They did nothing. I and Ravi were running around at the National Assembly speaking with lawmakers. I petitioned the then Attorney-General of the Federation, Bayo Ojo, to compel the government to act and prevent the death of Tochi but they did nothing. In my interview with Radio France, I said if Tochi was the son of a governor or a traditional ruler, Nigeria would have done something about it.

The lawyer also blamed the then high commissioner of Nigeria to Singapore for not taking Tochi’s situation seriously before he was ultimately killed.

“The Nigerian government, Nigerian Bar Association, Nigerian High Commission to Singapore…they did nothing.”

Princewill said while he was rallying support for Tochi, some Nigerians reminded him that Tochi was Igbo and so could be guilty.

“Even during an issue related to the life and death of a Nigerian, some were still stereotyping him. How then do we stop other countries from looking at us like criminals when we stereotype ourselves?”

I asked him if he could provide me with the contact of Tochi’s brother but he said he had lost it

“One of his brothers used to come here in those days in the period around the execution. They were grateful for the effort we put into the work. It’s quite unfortunate we did not get the result we hoped.”

I asked Princewill if he believes justice can still be served as Ravi suggested and perhaps Nigeria could petition Singapore at the International Court of Justice and sue for wrongful death but he wasn’t as optimistic as Ravi.

“Not this Nigerian government. I don’t believe this government will be interested so much in clearing the name of a young boy that was executed in Singapore about 15 years ago.”

Singapore’s death sentence

Singapore has one of the highest executions per capita in the world. The death sentence was introduced to the island city-state by British colonial rule and this was retained after independence in 1965.

There are a number of offences that carry the automatic death penalty: Murder, attempted murder or offences against the president’s person. However, the death sentence may not be imposed on pregnant women or anyone younger than 18 as at the time of offence.

Since 1991, most of the executions have been related to only three offences: Use of firearm, murder and drug trafficking.

Singapore has not provided any official data on executions carried out by the state. However, one of its well-known executioners, Darshan Singh, who did the job for 25 years starting in 1972 and also helped the previous executioner before his retirement, claimed he has been part of about 850 executions.

Recorded figures about execution in Singapore details the period from 1991 as little data is available for the period before then. Execution is usually done by hanging at a complex in Changi prison on a Friday before dawn. The condemned person is informed at least four days before it is carried out and within that period is allowed any food of their choice based on the assigned budget. Embassies and families of foreign nationals are informed about a week or two before the execution and are granted more visiting periods. They are allowed to claim the bodies after the death certificate has been signed or the state can cremate the body if it is not claimed.

Execution for drug trafficking has ranked very high among other death sentences, In the offence of drug trafficking which involves foreigners, this can sometimes cause diplomatic friction.

The state did not carry out any execution in 2020 due to COVID-19 pandemic but this may resume in 2021

I have written to the ministry of foreign affairs to make enquiries about the data on Nigerians executed abroad and I await their response.

The Nigerians in DIaspora Commission responded to #enquiry but referred Neusroom to the Nigerian Drug Law Enforcement Agency. An email was sent to the agency but no response has been given yet.