In 2017 an evangelical perspective influenced many political decisions, as President Donald Trump embraced the key constituency that voted overwhelmingly in his favor. As recently as Dec. 6, President Trump announced that the U.S. would recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, a move embraced by many evangelicals, for its significance to a biblical prophecy.

Earlier in the year Trump made several other announcements keeping in mind his conservative Christian supporters. He nominated Judge Neil M. Gorsuch, a conservative judge, to the Supreme Court. He also brought evangelical Christian leader Jerry Falwell Jr. to head the White House education reform task force, and Betsy DeVos, a conservative advocate of school choice, to serve as secretary of education.

I’ve been editing The Conversation’s ethics and religion desk since February 2017. As mainstream media outlets covered how Trump was embracing evangelical politics, at The Conversation we strived to provide historical context to these developments, as the following six articles exemplify.

1. History of the end-times narrative

Trump’s move on Jerusalem was widely understood as being linked to a biblical prophecy. Many evangelical Christians believe in an end-times narrative, that promises the return of Jesus to the Earth to defeat all God’s enemies, and establish God’s kingdom. The nation of Israel and the city of Jerusalem are crucial for the fulfillment of this prophecy. This is part of a theology considered to be a literal reading of the Bible.

However, Julie Ingersoll, religious studies professor at University of North Florida, explains that this theology is actually a relatively new interpretation that dates to the 19th century and relates to the work of Bible teacher John Nelson Darby.

Darby argued that the Jewish people needed to have control of Jerusalem and build a third Jewish temple on the site where the first and second temples were destroyed. This would be a precursor to the Battle of Armageddon, when Satan would be defeated and Christ would establish his earthly kingdom.

With the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, this theology suddenly seemed feasible and as Ingersoll further explained, the end-times framework became popularized in the 1970s and ‘80s through novels and movies.

“It’s impossible to overemphasize,” she writes, “the effects of this framework on those within the circles of evangelicalism where it is popular. A growing number of young people who have left evangelicalism point to end-times theology as a key component of the subculture they left. They call themselves 'exvangelicals’ and label teachings like this as abusive.”

2. The Moral Majority

Evangelicals have for decades played a prominent role in American politics. As the senior director of research and evaluation at USC Dornsife Richard Flory wrote, President Trump’s appointing Jerry Falwell Jr. to spearhead education reform is best explained by his family’s legacy.

Falwell Jr. is a relatively minor political and religious figure. It was his late father, Jerry Falwell Sr. who was, and continues to be, enormously influential in American politics.

Falwell founded the Moral Majority in 1979 as a conservative Christian political lobbying group that promoted “traditional” family values and prayer in schools and opposed LGBT rights, the Equal Rights Amendment and abortion – all key issues in Trump administrationas well.

“Republican candidates for office, dating back to Reagan and George H.W. Bush,” Flory says, recognized the power of the religious right as a voting bloc.“

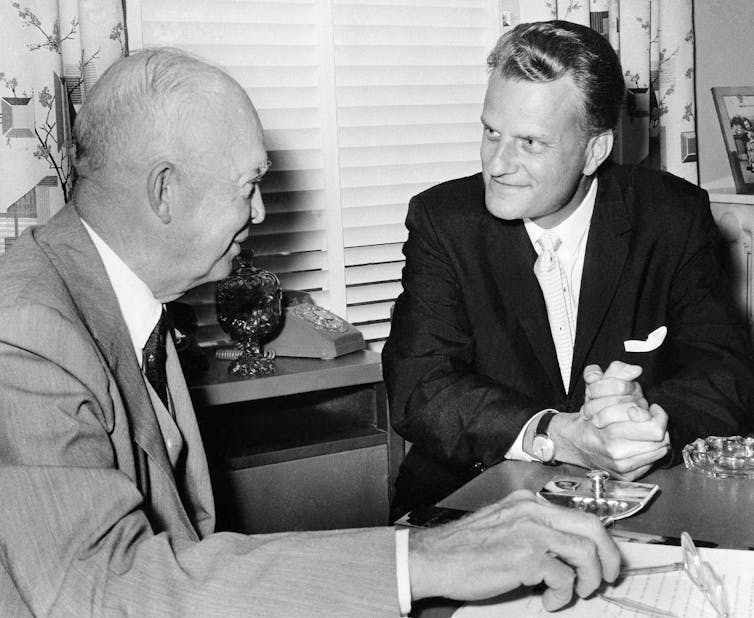

3. Billy Graham and Eisenhower

Before Falwell, it was evangelist Billy Graham who left a deep impact on conservative politics.

The National Prayer Breakfast, now an annual political tradition in Washington D.C., attended by the American president was a result of Billy Graham’s efforts with President Dwight Eisenhower.

As USC Annenberg religion scholar Diane Winston writes,

"Soon after his election in 1952, Eisenhower told Graham that the country needed a spiritual renewal. For Eisenhower, faith, patriotism and free enterprise were the fundamentals of a strong nation. But of the three, faith came first.”

It was, indeed, under Eisenhower that Congress voted to add “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance, and “In God We Trust,” to the nation’s currency.

And readers may recall that it was at the 65th National Prayer Breakfast that President Trump made an announcement to repeal the Johnson Amendment and allow religious leaders to endorse candidates from the pulpit, a pledge he made on the 2016 campaign trail. It’s another matter that the repeal was eventually dropped from the Republican tax reform bill.

4. Christian movements

Besides these prominent individual conservative voices, there are other Christian groups trying to shape American politics and the religious landscape.

Two of our contributors pointed in particular to a fast-growing Christian movement, that aims to bring God’s perfect society to Earth by placing “kingdom-minded people” in “powerful positions at the top of all sectors of society.”

Writing about this movement, Brad Christerson, professor of sociology at Biola University together with USC’s Richard Flory, explain how this movement regards Trump as part of that plan. Other kingdom-minded people include Secretary of Energy Rick Perry, Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos and Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Ben Carson.

Christerson and Flory believe this to be the fastest-growing Christian group in America and possibly in the world. Between 1970 and 2010, Protestant churches shrunk by an average of .05 percent per year but this group grew by an average of 3.24 percent per year. This number, they say, was “striking,” when considering the fact that U.S. population grew an average of 1 percent per year during this time period.

5. History of pluralism

Over the past year our scholars also pointed out how American politicians – starting with the nation’s founding fathers – have strived to be inclusive.

University of Texas historian Denise A. Spellberg told the story of a 22-year-old Thomas Jefferson purchasing a copy of the Quran, when he was a law student in Williamsburg, Virginia, 11 years before drafting the Declaration of Independence.

As she explains, Muslims who arrived in North America as early as the 17th century, eventually comprised 15 to 30 percent of the enslaved West African population of British America. The book purchase, she says, was not only “symbolic” of this connection, but also showed America’s early view of religious pluralism.

In Jefferson’s private notes was a paraphrase of the English philosopher John Locke’s 1689 “Letter on Toleration”:

“[he] says neither Pagan nor Mahometan [Muslim] nor Jew ought to be excluded from the civil rights of the commonwealth because of his religion.”

6. An inclusive nation?

Coming to the present, the question is how far has President Trump shifted the rhetoric of inclusiveness?

Trump, too, walked the “well-worn path,” in “proclaiming tolerance and highlighting commonality with Muslims,” wrote David Mislin, an assistant professor at Temple University. Analyzing President Trump’s address to leaders of some 50 Muslim nations during his visit to Saudi Arabia in May 2017, Mislin explained that Trump “used the language of a shared humanity and common God.”

However, Mislin also pointed out, that there was no acknowledgment in Trump’s speech of the Muslim population in the United States or of its contribution to American society. And that, “Islam remains something foreign” for Trump.

Indeed, in this administration – backed by over 80 percent of the white evangelical vote – “the legacy of Falwell Sr. lives on,” writes Richard Flory, “at least for the near term.”

Author:Kalpana Jain: Senior Religion + Ethics Editor

Credit link:https://theconversation.com/how-the-religious-right-shaped-american-politics-6-essential-reads-89005<img src="https://counter.theconversation.com/content/89005/count.gif?distributor=republish-lightbox-advanced" alt="The Conversation" width="1" height="1" />